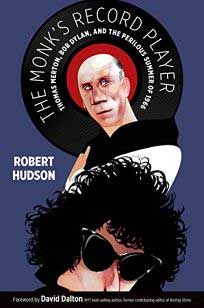

Thomas Merton, Bob Dylan and the Perilous Summer of 1966, Robert Hudson (263pp, £17.20, hbck, Eerdmaans)

The Monk’s Record Player is the most fictional of creative non-fiction books, a work based on conjecture and supposition, on possibilities, maybes and perhapses. It purports to discuss how the worlds of Thomas Merton and Bob Dylan might have intersected; how – without them ever meeting – they influenced each other and shared ideas; how they orbited and circled the same creative planets as each other: two very different shining stars.

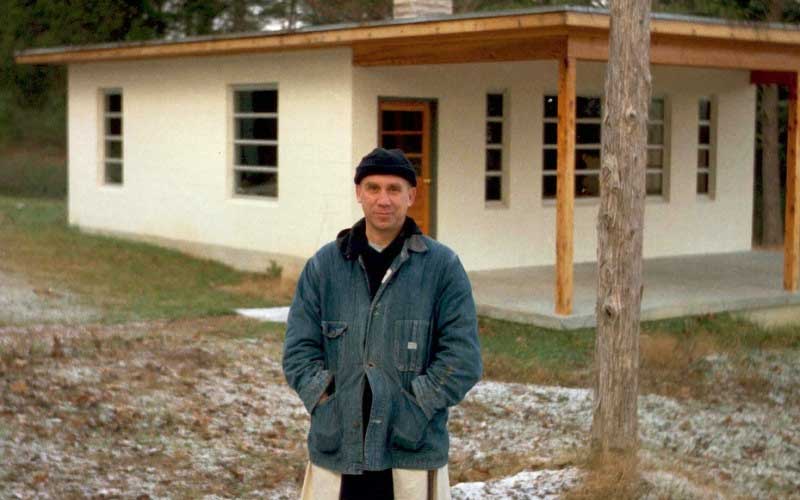

Thomas Merton was an enigma: a social hermit, a doubting monk, a down-to-earth mystic, who thought nothing of jumping over the monastery fence to take trips with his friends, or of holding impromptu picnics and drinks parties when visitors turned up. He wrote ‘cold war letters’ of pacifism and debate in response to being instructed to not write about the war, explored zen and sufi ideas, and managed to fall in love with a nurse; all the while maintaining (or just about maintaining) his monastic vows of chastity and obedience. And he wrote about it all, in voluminous journals and correspondence, all now published and in print, many years after his death.

What’s most fascinating to me is how he could in many ways be so isolated and so traditional a religious figure, yet be so wise, so able to see and comment on the world he mostly only saw from afar. His physical distance gave him mental space, the chance to ponder, digest, think and comment.

Of course, through a network of friends, publishers and correspondents, he was able to receive books and records, including LPs by a certain Bob Dylan, who was busy reinventing the protest song and electrifying folk music. Merton became obsessed by Joan Baez’s and Bob Dylan’s music (he met the former), and Robert Hudson shows, by referencing specific journal entries and examples, how Dylan’s stream-of-consciousness lyrics influenced Merton’s Cables to the Ace, a surreal long poem in 88 sections published in 1967.

So far, so good, if more of an aside or footnote than anything else. But Hudson somehow creates a whole book from this kind of thing. Well, actually he mostly vividly brings to life certain episodes of Merton’s life, then interrupts this story with chapters that reflect on Dylan’s life and music in, he suggests, a parallel world. It’s an enjoyable and lively romp through the mind of Merton, but the book says little about Dylan or Merton that hasn’t been said before, although of course, no-one has tried to pair or intertwine them in this way before.

I’m rather drawn to the book though. Like Michael Higgins fairly recent Heretic Blood (Wipf & Stock), which explores Merton through the work of William Blake, it is refreshingly irreverent and impious, and makes Merton complex and very human, rather than a minor saint. I’m not convinced that Dylan and Merton shared much between them – directly, indirectly or conceptually – but I’m glad they both exist and created what they did.

Rupert Loydell 2018