Rob Pursey and David Herd discuss the process of songwriting and poetry

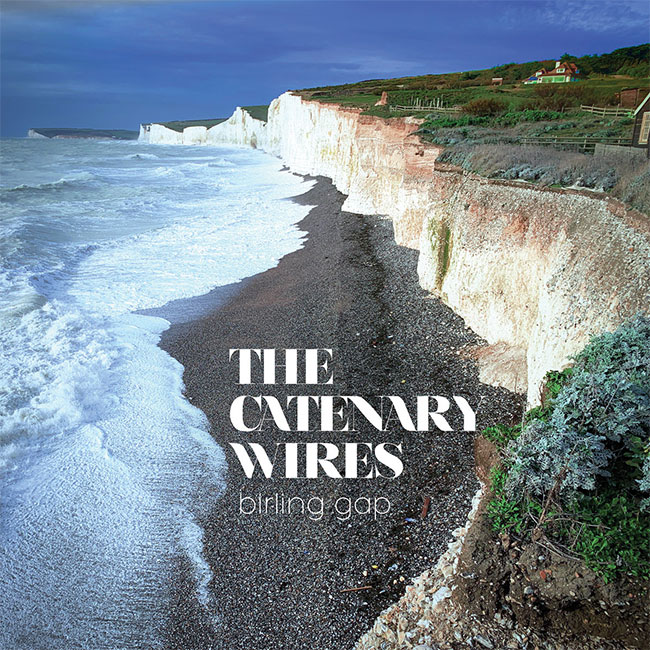

As a long-time fan of the work of Rob Pursey and Amelia Fletcher in bands like Heavenly and Marine Research, I was delighted to hear that their most recent project Catenary Wires had a new album out. Birling Gap has quickly become one of my favourite records of 2021, its 21st Century Folk-Pop songs thematic connectivity of England in a post-BREXIT landscape resonating strongly as voices from the edge. Of landscape, of life and of perception, perhaps.

Every song on the record is a tremendous treat, but the first song that connected most strongly with me, and that was subsequently dropped onto the Unpopular mix for May, was the mesmerising ‘Cinematic’. Musically reminiscent of Moose circa their criminally undervalued 1993 album Honeybee, the song shimmers like a sea mirage, sonically and lyrically nuanced; mysterious and suggestive rather than explicit.

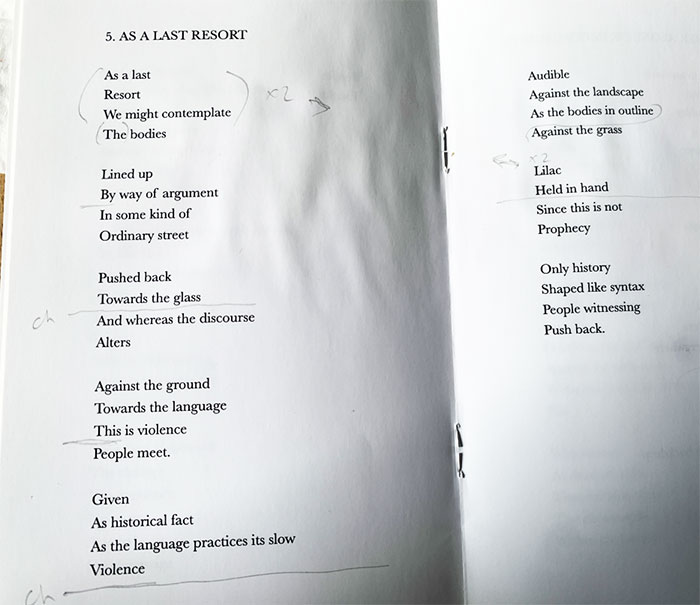

On closer inspection it turns out that lyrically ‘Cinematic’ is in fact an adaptation of a poem called ‘As A Last Resort’ by David Herd, so rather than write a straightforward review of the record, I thought it would be interesting to explore something of the various processes involved and where the realms of poetry and song composition might connect and/or diverge.

AF: What do you see as being the key, essential differences between poetry and lyrics? Do those differences change when thinking about poetry that is written to be read and poetry that is written to be performed?

Rob Pursey: For me, poetry comes with its own music. The rhythms are there, already embedded in the structure of the poem. Poetry is more complete. Lyrics, on the other hand, have to accept the rhythm that the music proposes. They can play against that rhythm, and they can disruptive when you want them to be, but for the most part they have to comply. Maybe the difference is a bit like that between a painting and a book illustration. The former stands alone and contains its own reference points. An illustration in a book complements and illuminates a piece of writing but doesn’t really have an independent life.

The physical sound of a lyric becomes very important when you’re singing it. If you want a line to end with a long note – one that might have a harmony on top – you need the last syllable to contain a nice long vowel so that there’s no problem stretching it out. The words you choose are very much influenced by this: they may be lucid and accurate and moving, but if you can’t sing them easily they aren’t going to be much good. A lot of songs get by without worrying too much about the sense at all. As pieces of writing they are poor, but as long as they sound OK, it doesn’t really matter!

I think the ambivalent status of lyrics is why a lot of bands aren’t keen on printing them alongside their recordings. These words weren’t designed to be read on their own, and sometimes they do look a bit naked when they can be scrutinised as pure ‘writing’. Having said that, people do like to sing along with records, and having a lyric sheet does make that a lot easier!

David Herd: Good question! So, the key difference between poetry and lyrics would seem to be that whereas poetry is stand-alone, lyrics are written in relation to music. That seems clear enough. The next question, I guess, is what difference does this difference make? In the case of the poem – at least from the point of view of the poem! – the words have to carry all the interest. If the lyric can lean on the music that is going on around it, the poem has to make all the music by itself. At the same time, if the lyric can lean on the music that is taking shape around it, it must also play its part in carrying the tune. One way or another, in other words, the lyric is a more collaborative mode.

But then the minute I write this, I know there is more to say. Any poem, for instance, is a collaboration in some way, perhaps with other poems or with other voices, or with the situation it wants to articulate. It’s not the same, for sure, as having a walking bass to answer to, but it does mean that the poem is, at some level, a collaborative act. So maybe the real difference is in the kind of listening that is involved. When you read a poem as opposed to when you hear a lyric, I think what you are listening with is the inner ear. It’s on that invisible element of the ear that the poem forms, where its play of sound and meaning emerge and take shape.

As for whether these differences change when the poem is written to be performed rather than read, the answer is: yes! Many poems, (though definitely not all) are written with both the act of reading and the act of performing in mind. But performing brings out a very different quality in the poem’s sense of voice. For example, one contemporary poet I love is Peter Gizzi, not least for the way his writing is at the intersection between poetry and lyric – he was deeply influenced by the New York punk scene of the late 70s and early 80s. When you hear Gizzi read you are hearing a poem in which the voicing is really important, where the poem itself is written in part to be said or spoken. But when you read the poem on the page you are constantly aware of the way the poem is making its voice out of its different elements, that voice itself is a constant performance. I guess the difference here might be the difference between hearing the poem in the time of performance and reading the poem in the space of the page.

AF: What poets and lyricists do you get most pleasure from reading/listening to? Do you recognise common threads between them? Stylistically as well as thematic, perhaps?

RP: Mark E Smith has been my favourite lyricist for years. When The Fall first started, he’d already written prototype lyrics in the form of poems. I don’t know whether he saw them as poems or as lyrics waiting for a song to turn up in those early days. But either way, the words had a primacy from the very beginnings of The Fall, and that was something the band never lost. And yet – the band, in its various incarnations, never lost its energy or its sense of spontaneity. There are various cliched tales of Mark E Smith disciplining the band, preventing them from improvising, and his on-stage antics, messing about with their amplifier settings, made for good theatre. But when you listen to the recordings you can hear Smith bending his words to celebrate the rhythm of the music. He wasn’t just ‘reading the words out’. He was performing them. He was too smart to try to neuter the band completely.

In terms of poetry, I like Milton (marrying epic, political tales to a very disciplined structure) and I like Geoffrey Hill. Hill I like in the same way that I like The Fall. There are shards of language that are clearer and sharper than anything you’ve heard. And then there is the density and complexity, which means there is always more decoding to be done. There is always something new to be got out of a re-reading (or in The Fall’s case a re-listen).

In terms of pop music, I think the Kinks are the band whose lyrics I love the most. The melodies are beautiful, and the words are perfectly chosen to convey those tunes. But at the same time, perfect and very precise vignettes of real life are conveyed. The Kinks knew how the music could make those portraits even more amusing, or moving or angry. I say ‘they’ because it feels like the whole band were tuned into this enterprise, even though Ray Davies is the songwriter.

I guess one thing these all have in common is that they were writing about the country we live in. They are capable of being emotive but are never sentimental. They all keep their brains in gear, all the time.

DH: Well, there are poets and lyricists I keep coming back to – obsessively re-reading and re-listening – and I am also always discovering new writers I love. So, for example, a book I encountered recently but one I know I will be coming back to for a long time is Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalia Diaz. Diaz is a native American poet who writes brilliantly from the politics of her position and for whom the poem is a constant negotiation between the intimacies of the body and violence of state-imposed architectures of space. As for lyricists from whom I get pleasure, one example would be Portishead, who as far as I understand it write as a collective and who are never so far down the playlist when the night gets late. And are there common threads? Well, there are many uncommon threads, but I know that that something I almost always want in a poem and a lyric – and basically in all cultural forms – is a play of voices. I like work that samples, collages, opens itself to interruption. I was lucky enough to be in conversation with Diaz recently and she spoke with great power about the play of languages in her writing – Mojave, Spanish and English – how they challenge, unsettle, dislocate and locate one another.

AF: I’ve spent the best part of 30 years as an educator in a High School setting exploring and reflecting on the meta-cognitive processes involved in learning, particularly in the realm of visual arts. So, I wonder, is there an underlying structure to your working practice that you recognise as a/the/your creative process? Is this even something that you give thought to?

RP: I’m not able to read music, so I’ve always done things by ear. I think a lot of people write pop songs like this. I do sometimes wonder if a bit of learning would help me, but then worry that the magic of stumbling across combinations of chords and melody would be lost. Anyway, it’s too late now!

I always come up with the tune first. Partly because I find that a lot easier – it feels like there’s no work involved in coming up with a melody. Lyrics, though, I definitely have to work at. Because we are writing pop music (of a kind) there would be no point having a song with fantastic lyrics and an indifferent tune. I wouldn’t want to hear that, and I wouldn’t want anyone else to have to endure it. The honest truth is that there are loads of songs that I love, sometimes songs I’ve known for years and will sing along to, where I still can’t make the lyrics out. It hasn’t spoiled my enjoyment (and maybe has even enhanced it!)

DH: This is hard, and I guess the answer is yes and no. I mean, I have ways of working, for sure, yes, but whether I want to write them down is another matter. For the most part, I guess, I’d rather catch myself in the act, where the act is the desire to open spaces of possibility. I like poetic sequences because of the relationalities they open up. The poem Rob and Amelia worked with to make ‘Cinematic’ came from a sequence called ‘Songs from the Language of a Declaration’. I l love the fact that the words of the poem now stand in the space of their song.

AF: David, that’s interesting what you say about poetic sequences and the relationalities they open up. I’m reminded of William Eggleston talking about his photographs. He said that he likes to think of his works flowing like music. He says it is one of the reasons he works in large groups rather than one picture of one thing. “It’s the flow of the whole series that counts.” Also, Martin Parr who says he “never thinks of photographs as being individual. Always as a group.” Rob, is that perhaps similar to the way an album takes form as opposed to individual songs? Not that I mean to get into the realm of ‘Concept Albums’, but…

Also, David, I’m interested in how you see Rob’s adaptation of your words to fit the structure of song, how some lines become repeated or moved around (I’m thinking that line ‘Lilac / Held in hand’) and a chorus (‘automatic, cinematic’) inserted. (Not sure if you’ve seen Rob’s photo of his editing process!) I’m assuming you are okay with all of that, but at what point do you think you would say ‘hold up there, that’s going a bit far…’. I’m guessing you are fairly relaxed about it, given your comments about liking work that “samples, collages, opens itself to interruption”.

RP: Once songs start to look like candidates for inclusion on an album, they do change. You start to notice the themes they have in common, and those elements tend to come to the fore – it’s like they’ve been remixed, as if a ’thematic similarity’ control on the mixing desk has been pushed up. The songs retain their individuality, and sonically they haven’t changed at all. But as their kinship becomes apparent you start to hear them differently. At this point you have a decision to make – whether to emphasise those thematic similarities, or whether to ignore them. With Birling Gap, we chose the former. We were very conscious of the risks associated with the ‘concept album’: to us it feels like a pompous idea, where the songwriting is subjugated to a message, or to a narrative that binds everything up too neatly. Luckily, we didn’t make the decision until most of the songs had been written, so they were ‘innocent’ of contrivance. But by now it was clear what linked them. While we were writing them, we, like most people, had talked a lot about England in the period dominated by Brexit, and we had allowed the songs to become platforms for little dramas set in this turbulent, anxious, argumentative country. Because most of our songs are duets, they do lend themselves to drama – the voices don’t always sing directly to each other, but with two characters ‘on the stage’ there is inevitably a dramatic relationship between them. A couple of the songs are very directly about the crisis in English identity: Three Wheeled Car is about a nationalistic couple heading to the seaside to celebrate the splendid isolation of living on a sealed-off island; Alpine is about a middle-class Remainer couple whose political imagination (and relationship) hasn’t moved on from a skiing holiday when they first fell in love, and when travel to Europe was a badge of their wealth, success and apparent sophistication. In other songs the theme was less discernible: Liminal, for example, is about looking after someone who is very close to death: but the characters in that song inhabit the same time and space as all the others. Anyway, we decided to cast a net over the whole thing by calling the album ‘Birling Gap’. The real location, on the Sussex coast, combines a lot of elements that the album touches on: there are the fabled white cliffs beloved of patriots, the sheer drops into the sea that mean the spectre of self-destruction is never far away – and there’s that constant nagging anxiety that derives from a landscape where climate change is making a very obvious impact.

Cinematic was the last song to go onto the album, and, by the time we got round to recording it, we had decided what the album was about. So there was a risk that this song would become self-conscious – trying too hard to fit in. I think this is one of the reasons I reached for David’s poem! I knew the song wanted to be about the disengagement and callousness people adopt as a response to the sight of migrants attempting to reach the South Coast of this country, across the English Channel. That yielded the chorus – cinematic / automatic / it’s what we do – I was imagining people impassively watching news images of migrants in little boats from the safety of their living rooms, but that’s as far as I got!

DH: So I guess I think there is a big difference – a world of difference in way – between a concept album and a poetic sequence or series. Rob’s description of a concept album seems completely right to me: that everything is wrapped up all too neatly by the central idea or narrative. A sequence, or series – I’m going to go with series now, though there are subtle differences to be sure – is pretty much the opposite. A really good series of poems, say by Wallace Stevens or Lorine Niedecker, knows that it is not unfinished and that its not being finished is completely the point. So what I like in a series of poems is the play of similarity and difference, the ongoing variation across a thematic and all the openness to change that implies. James Schuyler was great at that, in a work like ‘The Morning of the Poem’ for instance, as is Susan Howe. Having a poem reframed and resituated the way Rob and Amelia do with ‘As a Last Resort’ seems to me to be continuous with this play of change across a series and I think, as you say Alistair, that it’s all closely connected with collaging and sampling. All the poets I like most start from the basis that the words they are using come from somewhere else, whether from another poem, or from conversation, or from some other kind of text or document. Making is re-making where the point is not to allude or reference, but just to acknowledge that the language is a material that other people are always using and have used. But I’m really interested to know how this relates to what Rob calls the ‘thematic similarity’ control that underscores the writing of an album. I really like the fact, by the way, that Rob connects Milton and Mark E. Smith. I love Milton too (for all the reasons you say, Rob, and more) but sometimes I’m not sure if he was more concept artist than maker of poetic series. The way you talk about MES, on the other hand, reminds me of John Cooper Clarke, but I’m not sure who came first. And as I write I guess the question that is occurring to me is how the idea of the ‘song’ relates to this question of lyric and poem? Birling Gap is a collection of wonderful songs. Is there some guiding sense, underpinning of that, of what makes a song?

RP: I can maybe answer that best in relation to a specific song. As it’s the subject of our discussions, I’ll use Cinematic as my example. It’s not a process I’ve ever thought about properly before, so apologies if this is long-winded or incoherent.

First of all, there’s a set of chords that come to me when messing about with the guitar. It’s definitely not a song yet – just an unnamed but pleasing set of chords. Playing it over and over to myself it seems to conjure something – it seems to have potential. Then I think of the vocal melody. Now there are two musical elements – the melody and the guitar line – and it’s starting to take on a life of its own. It’s not a song yet, though. Then, a new vocal tune suggests itself and leaps ahead of the verse chords: a chorus is starting to form. I have to work quite quickly at this point because if I don’t figure out the accompanying chords, that tune will be forgotten! I establish what the chords are – A, F, G, A, F, C, G – and the melody has been nailed down. That’s quite a relief. It’s captured now and can’t escape.

I like it, this almost-song, the way the verse and chorus play against each other, and there’s already an implication of relentlessness, and even cruelty, when the chorus gives way and the verse resumes. I can’t describe why it feels like that – I wonder if I am hearing echoes of other songs? If so, I can’t identify them. Anyway, that hard-to-define ‘feeling’ will determine what the song will become ‘about’. But now, there is an important test. This song, if it is indeed to become a song, has to be played by the group, and they have to be enthusiastic about it. I play it to Amelia, improvising nonsense lyrics just so I can convey the melody to her. She likes it well enough, so I feel confident enough to pursue it. It’s still not a song yet, though.

Now I record the bass and guitar as a rough demo. The lyrics for the chorus start to crystallise from those ‘nonsense words’ I sang to Amelia (I sang them without thinking about them, and that’s probably why they sound right). Now I start wondering what they mean! ‘Cinematic, automatic…’ The themes of callousness, emotional distance and inhumanity are all still there, and are getting louder. Now, I have to work on the words for the verse, but my ‘nonsense lyrics’ really are just that: nonsense. They bear no relation to the theme of the song. I need to write them from scratch. But at this point I remember David’s poem ‘As A Last Resort’. I’d first read it a couple of weeks before, and it’s stayed with me. I’m also thinking about David work with Refugee Tales – an organisation that campaigns for the rights of asylum seekers, and asserts the humanity of the people caught up in the UK’s immigration system. That’s what this song wants to be about. So, rather than try to write new words I have a go at singing the words of the poem. Fortunately they fit the melody with remarkably little manipulation. I can’t imagine writing better words than these. ‘Cinematic’ is complete – it’s definitely a song now. But with ‘Cinematic’, there is one more thing I have to do. I need to make sure David is happy for me to take advantage of his poem in this way. I am very relieved when he says ‘yes’.

AF: Yes indeed. And there is something in the way in which the initially unseen ‘collaboration’ taking place in the making of the song is, in itself, a reflection on the many positive interactions between refugees/migrants and the so-called ‘indigenous’ British public. Such interactions may be unseen and certainly un-reported, but nevertheless create bonds forged from shared experiences, thoughts, feelings, ideals or whatever. The energy of connectivity is perhaps more subtle yet more profound than that of division and fear. I certainly hear that sublime positive energy in ‘Cinematic’ and in the entirety of Birling Gap. And now that I’ve been introduced to David’s work I am looking forward to reading more of it in his words.

Birling Gap is available on the Skep Wax label in the UK/Europe: https://catenarywires.bandcamp.com/album/birling-gap

and Shelflife in the USA/North America: https://catenarywires.bandcamp.com/album/birling-gap-north-america-only

David Herd is Professor of Modern Literature at the University of Kent, and has worked with Kent Refugee Help since 2009. He is a coordinator of the Refugee Tales project https://commapress.co.uk/authors/david-herd/

David’s work has also been published by Carcanet https://bit.ly/3gYqVuM