Modern Buildings in London, Ian Nairn (Notting Hill Editions)

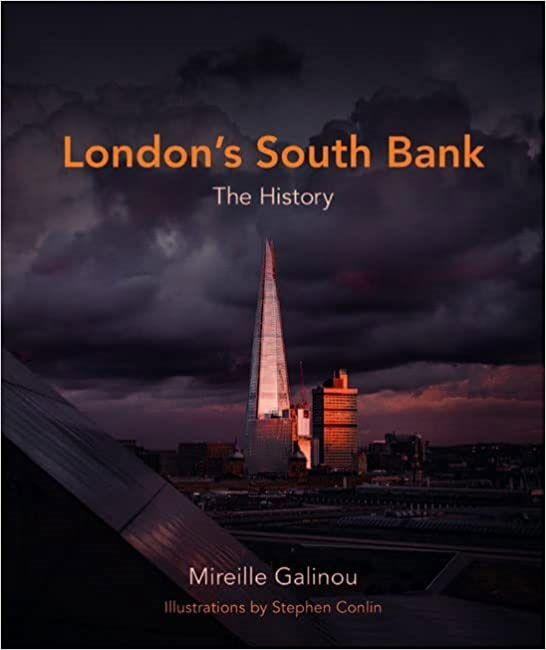

London’s South Bank. The History, Mireille Galinou (Your London Publishing)

I’ve never quite got the still-growing cult which fetishizes Ian Nairn’s opinionated books about architecture. His gazetteers are little more than brief summaries and commentaries fuelled by personal likes or dislikes, and outrageous statements more rooted in the moment than any considered position. For instance, Nairn declares Jacob Epstein’s Madonna and Child in Cavendish Square to be ‘almost the only worthwhile piece of sculpture in Central London’, although this is immediately undermined by the ‘(see also 12)’ which refers the reader to an entry on State House, Holborn and Barbara Hepworth’s Meridian, which he clumsily describes as ‘a helix or spiral which has first been elongated and then given corners, and hence a skipping polygonal rhythm’, having first compared it to ‘a dynamo whirring away in a private world’.

Even in 1964 this uninformed take on art and architecture must have seemed pretty thin. Are phrases such as ‘personal and homely’, ‘[n]o masterpiece, but something just as important’, ‘a sad end to a great talent’ and ‘[a] terrible performance’ of any use to the reader, let alone the ridiculous ‘[t]his is a good place to come if you think that modern architecture cannot provide mystery and poetry’? What on earth has architecture got to do with either mystery or poetry? It is about materials, design, use of space, setting, light and usability; all things Nairn mostly ignores because it quickly becomes apparent that he has mostly stood outside the buildings and looked up some information about the architect. He mostly conjectures, assumes and generalises alongside brief descriptions.

It’s unclear what Nairn really thought of the then new and ‘modern’ buildings he included here. He occasionally worries about issues such as the fact that ‘[w]hen a building as thoughtful as this [New Zealand House, Pall Mall] is a disruptive influence, then it is time to question the whole basis of tall blocks in cities’, going on to offer the throwaway yet pertinent conclusion for that entry that ‘[t]he real problems of modern architecture are just beginning.’ It’s strange how these issues are (mostly) hidden away within Nairn’s more forthright and generally upbeat takes on the houses, offices and schools included here. Unfortunately Nairn’s alcoholism and death, not to mention 50 years of demolition, extensions, alterations and grand architecture, mean that we will never know what he would have made of the lovely architectural chaos that comprises London now; and we now have only photos and the likes of this book as evidence that many of these buildings existed. I remain ambivalent about Nairn’s writing, but – to use on of his phrases – at least ‘[s]omebody really cared.’

Mireille Galinou Galinou also cares about London. Her beautifully designed and printed book is both a history and a personal exploration and response to the South Bank, which she regards as ‘the centre of gravity for London’. For the purpose of this book the area includes Vauxhall and Lambeth, Waterloo, Borough and Bankside, Southwark and Bermondsey, and not just the area around the Festival Hall, Hayward Gallery and National Theatre the name is so often used for.

Galinou starts her story in 2007, when Antony Gormley’s life-size sculptures were somewhat unnervingly placed around the area, backpedals to The London Eye (has it only been there since 2002?) and then with a hop, skip and a jump we are back in the Middle Ages. Galinou is good at telling the history of London in both general and specific ways: we get to see early maps of the city and to read a discussion of and be shown details of A fête at Bermondsey, the first London landscape painting, Galinou is expert at interpreting the details and social customs and events included in the painting, as well as considering the source material and the fact ‘it is described as “an imaginary landscape”‘, despite the inclusion of ‘the very recognizable Tower of London’ and other details.

The use of historical and artistic sources (of course, they are not exclusive) continues, with fascinating considerations of how South London was sometimes painted out of views, the great fires of London (yes, plural), and how art and topography differ. The last topic returns us to the 21st century with Sharon Beavan’s unfinished painting of the wide-eyed view from Blackfriars Bridge, wherein the buildings buckle and distort into patterns as the result of shifting points of view. Galinou briefly notes the importance of high views, noting how The Shard has recently produced a new one, before descending into a slightly uneasy installation piece in Clink Street which she argues evidenced ‘the soul of London’.

And then in Chapter 3 we are privy to ‘The Sweep of History’, seen in the first section mostly through archaeology, with brief discussion of the wooden jetty from 1500 BC whose remains have been found at Vauxhall and the Iron Age Waterloo Helmet, then the Roman necropolis, boats, encampments and temples, and finally the Domesday Book which shows only a low number of homesteads in the area. The next sections specifically focus on the time ‘around 1600’, 1770, 1845 and now, with each of the four South Bank areas getting their own brief sub-section (a device I initially found quite confusing). For each date, there is a map and gazetteer of important buildings and geographical features – big houses, gardens, marshes, churches, prisons, schools, theatres etc. – from the time, accompanied by contemporaneous prints and paintings. It’s fascinating to see how quickly the area develops and changes, what industries come and go, how the Thames is always present as both a thoroughfare and a divide.

The final section of the chapter ‘The South Bank now’ is briefly introduced with references to ‘Millennium Fever’, ‘Housing’ and ‘Hotelmania’, as well as a consideration of how ‘[t]he ghost from the past is still haunting the present’, principally by the reconfiguring of warehouses and other buildings for contemporary use (e.g. Tate Modern) but also the resurrection and reconstruction of The Globe Theatre. Then, within each area’s section we get socially and politically contextualised descriptions of recent and contemporary buildings. The information and detail evidenced here only reinforces my opinion of Ian Nairn, above: Galinou’s entries are informed, referenced, astute and informative.

Having devoted much of the 300+ pages so far to the historical and recent pasts, ‘The Quest’ (Chapter 4) tries to ‘find the soul’ of each of the areas. Vauxhall and Lambeth is presented as ‘Paradise Regained’, with a wander through the parks, pleasure grounds and nature of the area, along with a brief pause to read William Blake’s critical consideration of London, in his poem of the same name, which Galinou suggests is ‘the antithesis of the Garden of Eden’, ‘the fallen city groaning with the cries of its enslaved dwellers.’ She suggests his experience ‘revolved around two opposite poles: blissful contentment in the “Nest” [his home], fallen humanity when stepping out of the front door, though tampered by the hope of finding infinity.’ Squares and gardens and parks, along with The Garden Museum, still bear witness to the presence of public spaces and greenery and offer one possible focus for the city’s future.

Waterloo’s soul is a darker one. Galinou uses Blake’s dark visions and desire for London to become a new Jerusalem as a preface for a litany of drowning, murder, imprisonment, which evidence the ‘Fallen neighbourhood: Lust, Greed and Sloth’. It is not clear whether the railways and Waterloo Station helped the demise or the resurrection of the area, although George Augustus Sala is decisive in his 1858 judgement of the nearby New Cut:

It isn’t picturesque, it isn’t quaint, it isn’t curious. It has not even the questionable

merit of being old. It is simply Low. It is sordid, squalid, and, the truth must out,

disreputable …. It is horrible, dreadful, we know, to have such a place: but then,

consider – the population of London is fast advancing towards three millions, and

the wicked people must live somewhere

Social reformers seemed to have been one of the catalysts for change in the area, but the popularity of music hall theatre at the end of the 19th Century slowly led to a resurgence of theatres on the South Bank, The Old Vic being instrumental. Later, of course, The Festival of Britain attracted many thousands of visitors and was instrumental in the development of institutional support for the arts. It also, of course, gave us The Festival Hall, and helped prompt the redevelopment of other areas on the South Bank. Galinou sees the example of, for instance, the community redevelopment of Coin Street, with its housing co-ops, neighbourhood centre and the Oxo Tower Wharf unit, as a challenge to what she calls the Goliaths of the development industry.

Theatre also features in the section on ‘Borough and Bankside’, but it is overshadowed by cholera and fire, cemeteries and death. Only when the industrial warehouses are abandoned can the likes of Derek Jarman live, create and party in spaces on the South Bank, slowly leading to formal studio provision and then the creation of Tate Modern, both an artistic and tourism success story. In this quarter, Galinou sees the ‘fluent marriage of the past with the present’ as key.

She seems less enthusiastic about The Shard, which gets discussed in relation to the Tower of Babel, and gets blamed (admittedly by Tom Ball, a member of the public, and not the author) for setting ‘a precedent for a flood of huge and tall buildings’ which will ‘spell an end to for London’s much admired human scale.’ Hmm. Shades of Prince Charles’s ignorance and interference here it seems. More reasoned perhaps is the objection to unsympathetic redevelopment which has not helped what Galinou calls ‘[t]he social pecking order’. The area is also considered in terms of its previous role as ‘London’s larder’ and the way contemporary microbreweries, food markets and restaurants have recently colonised the area, as well as those artists – such as Jarman again – who made use of abandoned warehouse and factory spaces. It is a combination of the new food and drink industry with the notion of a corporate identity that Galinou identifies here as key for future development.

In the final chapter, she expounds her ‘Answers to the quest’ from each area and section of the previous chapter, presents a fictional dialogue between an archaeologist and an architect on the back of asking them the same questions, and briefly touches upon the ‘disconnect between science and human emotions’ and ‘mental paralysis in the face of multi-culturalism’. The answer to these and other issues, she suggests, is already in existence: ‘a neighbourhood has grown which embraces art, compassion and healing’, which ‘has metaphysical, philosophical, artistic and spiritual undertones.’ This is neither vague utopian dreaming nor Conservative abdication of responsibility, it is what Galinou has already seen, alive and well today yet rooted in the past, for herself. The city, she suggests, is people not buildings, and everyone who lives in (or visits) London, must engage and be an active part.

This is a wonderful, optimistic, informative and ambitious publication. It manages to be a cultural and social history, an artistic engagement, a provocation and a rallying cry. It celebrates and mourns the past, documents the present, and offers up possibilities and challenges for the future, all in an engaging and individual manner. How rare this combination is. Go on, treat yourself to a copy.

Rupert Loydell