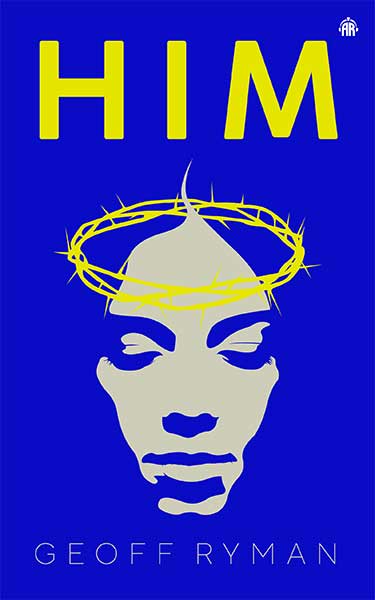

Him, Geoff Ryman (Angry Robot, £9.99)

Geoff Ryman’s publishing career has been notable – in addition to its creative brilliance – for the fact that each book creates an entirely new world. The Child Garden imagines a swamp world around London, with the human race affected by genetic modifications and a hive mind, whilst Air imagines a world where the internet becomes alive, in the air, and everyone is automatically connected. In between those two there was 253, an internet hypertext (later published as a book) which presented brief lives of all the passengers on a tube train, and Was, a novel exploring the world of The Wizard of Oz in three interwoven strands: Dorothy experiencing being orphaned and then adopted in the historical Depression era, a gay couple obsessed by the musical film version, and a fictional biography of Judy Garland.

There are others, too, but in his new novel, Him, Ryman takes on an even bigger story than Oz, the story of Jesus. He joins the throng of authors, filmmakers and poets who have reinvented or adapted the story, be that as Shakespearean declamation, hippy rebel, guerilla freedom fighter, madman or quiet subversive; everyone has their own idea, since until recently most people knew the story or stories. However, no-one that I know of, has imagined Jesus (or Yeshu, in this novel) as a girl who not only wants to be a boy but also the Son of God, a precocious child who refuses to answer to her given name or have anything to do with being female.

Whilst some of the blurbs suggest that this novel will upset some readers (Neil Gaiman predicts it will be ‘burnt on bonfires’) I can’t see it myself. In fact apart from the fact that Jeshu breaks some Jewish rules about where men or women can and can’t go in the temple, and what they can or can’t do, the gender issue is an aside for most of the book, as Jeshu makes his way through life as a male, enjoying being part of a gang of boys in his village, and then taking on a manual job for the local stonemason, before the second part of the book arrives and we find him preaching and teaching as he wanders the land with his followers.

This is a book about families, about familial expectations; about societal conventions and norms; about poverty, survival and learning; about male and female psychologies and relationships. It is about the difference between reading and knowledge, about the differences between siblings, and about a mother/son relationship where Maryam comes to accept her child’s dreams and ambitions, his teaching, finally embracing it only for it appear to go wrong. It is a hot, tired and sweaty book, where people try to survive in the harsh deserts and broken villages of an occupied country; it is about monotony, repetition, class and survival.

Jeshu, of course, offers a different way forward. He can heal people and perform miracles but is wary of becoming known for that. He talks in riddles and parables, entertaining and confusing the crowds, who do not like it when he turns serious or starts talking about his death. Slowly the book moves towards where we know it is going… Jerusalem and crucifixion. The entry to Jerusalem, palms waved over a triumphal king on a donkey happens, but almost by accident. Later, in various hearings and courts, Jeshu’s followers try to get him off the hook, released, but he will insist on provoking not only the Jewish political and religious leaders but also the Roman officer in charge of the region. So Jeshu is sentenced to death. Even a last minute legal challenge is thwarted, so Maryam and the others are forced to accept the inevitable.

There is little mysticism or religion in Ryman’s version of things. There is an understated magic, or ability to heal, and ideas about dealing with oppression and poverty, of ‘the Kingdom of God’ and the here and now (we might call it ‘living in the moment’) but it is enmeshed in human struggle, argument and ambition. Jeshu’s followers are broken, selfish, flawed people and have their own ideas of what their leader is saying, and his preaching, lifestyle and actions break up his wider family. It is ultimately unclear in Him what his death achieves, although it seems to be physically manifested by the weather and to somehow reunite him with his mother. There is no resurrection here, nor any suggestion that Maryam is some sort of female deity or saint, although she has repeatedly and matter-of-factly conceived without intercourse.

Ultimately this is a book that humanises the Jesus we know historically existed but that the church has since used to its own financial and power-grabbing ends. Ryman’s Jeshu is confused, awkward, determined and persuasive, whilst his mother struggles with what he and his siblings become, and takes much of the book to accept what is happening before she joins the travelling throng of supporters and hangers-on. Despite a rather awkward and sometimes distancing adoption of Jewish terms and names, the book grapples with human comprehension and understanding when words run out:

It was too big for words, but that didn’t mean it wasn’t

true. Too big for words was almost a guarantee that it was

true.

There is almost too much going on in Ryman’s version of things, his book is full of asides, distractions and red herrings, with little followed through. If the priests don’t know that Jeshu is female by birth but presents as male, it feels that the discussion and argument they have is not changed by the reader knowing. The gender issue feels imposed on the narrative, whereas AIDS and being gay in Was – written at the time of the AIDS crisis – was groundbreaking and timely, as well as being crucial to the story. Here, it is not a focal point of the story in the same way.

Him is an intriguing mix of contemporary values and ideas put within an historical novel that works hard to present a realistic society and geography. Jeshu is out of time and place, an oddity in a society of rules and rituals, one who questions, challenges and provokes everyday expectations and norms, religious convention and God himself. It’s good to meet another version of the central character, whose life is defamiliarised and told anew; even better to have surrounding characters brought to life. Him isn’t Ryman’s best book, but it is an intriguing new version and reminder of a story we already kind of know.

Rupert Loydell

.