‘Up and down the Westway, in and out the lights, what a great traffic system, it’s so bright.’ The Clash ‘London’s Burning’.

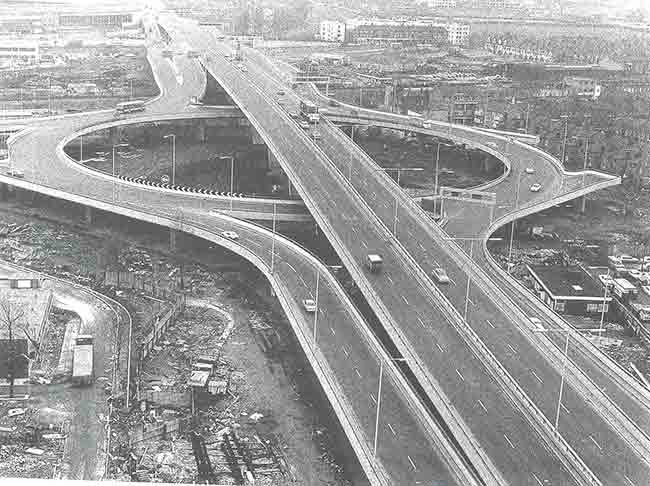

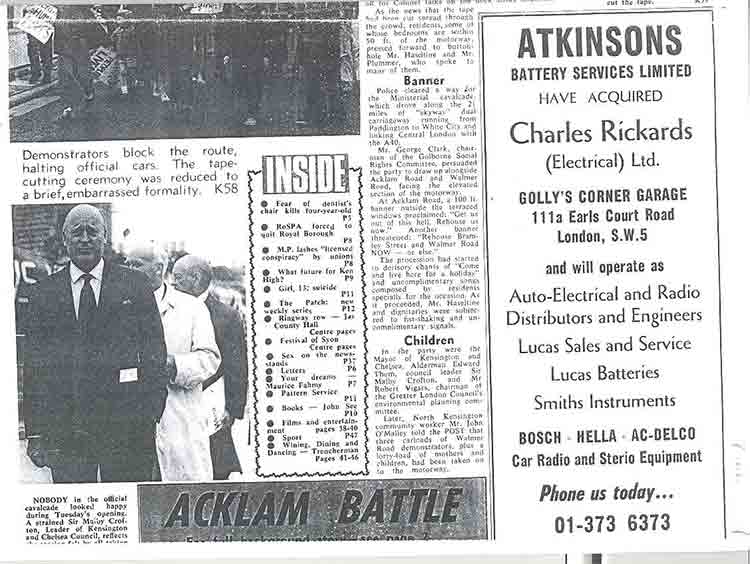

50 years ago on July 28 1970 the iconic Westway flyover was opened. The A40 Western Avenue Extension, as it was officially known, between White City and Paddington, at 2½ miles the longest elevated road in Europe at the time, was opened by the parliamentary secretary to the transport minister, Michael Heseltine, and was accompanied by a protest over the re-housing of residents of Acklam Road and Walmer Road beside the flyover. As demonstrators disrupted the ribbon cutting, a banner was unfurled on the rooftops of Acklam Road demanding: ‘Get Us Out of this Hell – Re-house Us Now’. In the background Trellick Tower can be seen nearing completion in Kensal. The Telegraph captioned a picture of the ‘giant concrete cartwheel’ Westway roundabout at Latimer Road: ‘Last link in road to west is forged.’ Soon 47,000 vehicles a day began ‘cruising through the rooftops of North Kensington.’

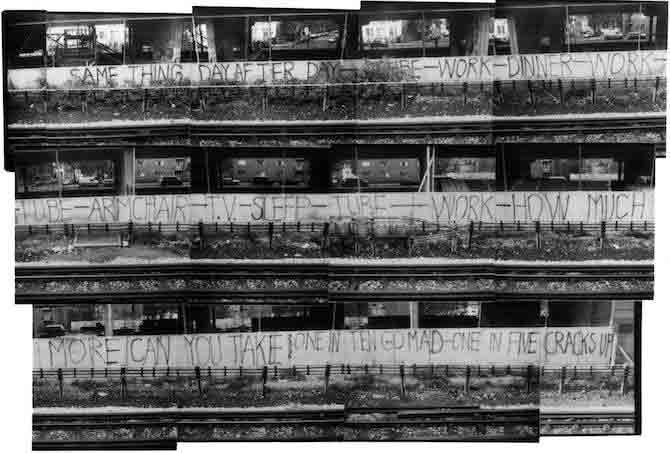

During the 4 years of construction work, for the inhabitants of the north side of Acklam Road and the other surviving terraces close to the flyover, ‘continuous noise and dirt from heavy lorries and machinery became a familiar and unwelcome part of life.’ The sound of the Westway being built was described by Eileen Wright in ‘Taking on the Motorway’ as a wartime experience: “There was a terrible noise for weeks when they were pile-driving. They started at 6 O’clock in the morning – sometimes it went on all night. You think the whole city is being bombarded beneath you.” Hoardings alongside the Hammersmith and City line beneath the Westway featured graffiti by the Situationist King Mob group that read: ‘Same thing day after day – Tube – Work – Diner (sic) – Work – Tube – Armchair – TV – Sleep – Tube – Work – How much more can you take – One in ten go mad – One in five cracks up.’

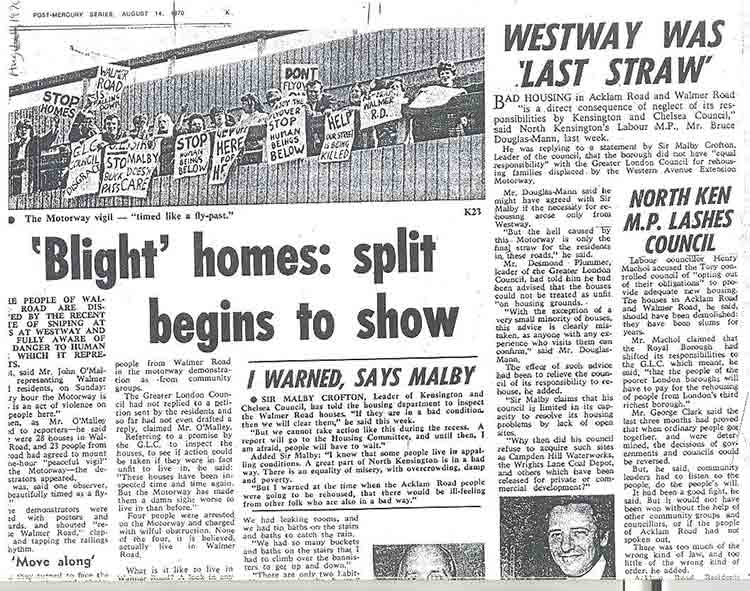

At the opening Michael Heseltine told the press: “There are two sides to this business. One is the exciting road building side but there is also the human side of this thing, and how huge roads like this affect people living alongside them. You cannot but have sympathy for these people.” The Standard reported that: ‘the ministerial cavalcade later drove the length of the twin dual-carriageway running from Paddington to White City. On the way it passed Acklam Road, where bedrooms of houses are less than 50 feet from the elevated section of the road. Here the GLC is proposing to spend £250,000 buying 42 houses which have been ‘blighted’, demolish them and turn the land acquired into a buffer state.’ The Acklam Road residents’ representative George Clark protested to the Transport Minister John Peyton (who said he couldn’t attend the opening because he had to be at a cabinet meeting): “I want to make a statement to the minister about the hell on earth in North Kensington. During the 5 years it has taken to construct this engineering marvel, the lives and social conditions of the residents of Acklam Road and Walmer Road have been made hell upon earth. For these people the new urban highway is a social disaster.”

The Westway opening protest developed into a local dispute between Walmer Road and Acklam Road, and George Clark was blamed for holding up the re-housing of the former tenants in favour of the latter. As the 1967 housing activist saint was consigned to Notting Hell, a placard proclaimed: ‘There’s only one man I know who could live in this hell hole and that is George Clark – the devil himself.’ In the International Times report, entitled ‘The Devil is alive and well and living in Notting Hill’ (under a picture of Mick Jagger in ‘Performance’), Clark was accused of ‘diverting justifiable community anger from radical action into harmless words.’ IT concluded that ‘the motorway v Walmer Road is merely the latest illustration of the fact that the Gate community is crumbling.’ Walmer Road was described as: ’28 houses, approximately 173 families. The houses are typical Notting Hill residences: rotting, damp, vermin-infested holes with imploding ceilings and leaking lavatories, where the landlords send round agents to collect the rent to avoid facing angry tenants or hearing their complaints.’

On August 9, as the Westway opened to traffic there was another re-housing protest on the hard shoulder, and on the same day there was a protest march under the flyover. In the late 60s and early 70s there seems to have been a demo in Notting Hill virtually every other day, while All Saints hall hosted at least one community action meeting a night. The march was protesting about police persecution of the Mangrove Caribbean restaurant at 8 All Saints Road, outside of each of the 3 local police stations; the Notting Hill station on Ladbroke Road, Sirdar Road in Notting Dale, and the plan was to finish at Harrow Road. But, as the march went up Great Western Road, under the newly opened Westway, police attempts to divert it away from the Harrow Road station resulted in a mini-riot on Portnall Road, the arrest of 17 demonstrators, and the infamous trial of the Mangrove 9.

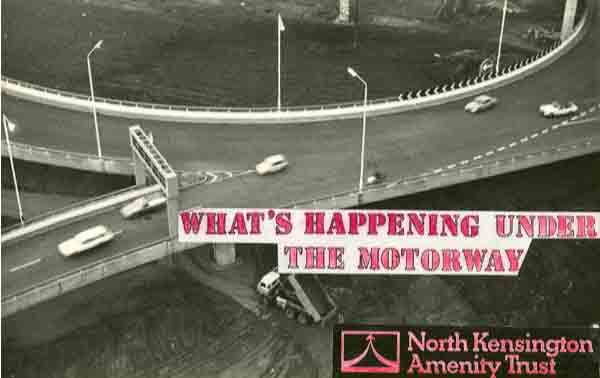

As construction work began in 1966, after the London Free School community action project, the North Kensington Playspace Group was formed by Adam Ritchie and John O’Malley of the Notting Hill Community Workshop. In 1968 the Playspace Group became the Motorway Development Trust, and planned to create a community strip featuring a laundry, cafe, health centre, nursery school, playgroup, sport area, and adventure playground which opened on Acklam Road in 1969. Following the re-housing protests and a campaign against the GLC plan for a bus garage between Portobello Road and Ladbroke Grove, another local political struggle with the Council developed for control of the Motorway Development Trust. Out of this in 1971 came the North Kensington Amenity Trust, with a half-Council, half-community management committee. The purpose of the trust (which duly became the Westway Development Trust) was to develop the 23 acres under the flyover for the benefit and use of the local community.

Andrew Duncan wrote in his introduction to the Westway book ’Taking on the Motorway’: ‘Out of a 4-year campaign, North Kensington Amenity Trust was set up in partnership with the local authority in response to two demands: The mile strip of land under the motorway which lay within the borough’s boundaries should be used to compensate the community for the damage and destruction caused by the road; and the 23 acres should be held in trust to ensure that local people would be actively involved in determining its use. The story of the trust is one of conflict, for it was born out of bitter clashes between an angry local community and the two planning authorities that gave consent to the motorway intruder – the GLC and the RBK&C. But it is also a story of hope…’

The first director of the trust was Anthony Perry, a film producer who had worked on the Beatles’ ‘Yellow Submarine’. He concluded that developing the Westway land ‘would call for qualities not unlike those needed for producing a film’, went for the job and got it. In his diary of the trust’s first 5 years, ‘A Tale of Two Kensingtons’, he pondered: ‘What is the Amenity Trust? In the very simplest terms, it is a charity that has been set up to develop the 23 acres of land under the elevated motorway in North Kensington in the interest of the community. No thought was given to the social implications for this working-class neighbourhood at the time the motorway was planned. The trust was set up in response to the great energy and pressure of a small number of local people. The council wanted me to take an office at the town hall but it was essential I be on the spot so I occupied an empty house waiting for demolition, on the corner of Portobello and Acklam Road, and set up shop on May 28 1971 with the help of Pat Smythe, a tough resourceful member of the management committee who had set up the first adventure playground in Telford Road. 3 Acklam Road was one of a row of houses due to be demolished as being too close to the motorway. I subsequently got them reprieved and we did some repairs and re-wiring and gave rooms to local groups. Our office was the one overlooking the junction with Portobello Road.

‘At that time Portobello Green, as I named it, was completely fenced in with a high corrugated iron wall. It had been the site of the lorry ramp leading up to the motorway during its construction. I sold it to a scrap dealer on condition he removed it. I then declared it open to the public. Over the weeks that followed we slowly cleared it up with volunteer labour – not exactly volunteer, I paid them £1 an hour. We tarmaced the part immediately adjacent to Portobello Road and started a charity market, fencing it off from ‘the Green’ with timber posts cut from surplus telegraph poles. The London Brick Company gave us a lorry load of over-baked bricks and a Canadian student laid out an attractive sitting area. I had tree surgeons in to save the bedraggled trees bordering Cambridge Gardens. The thing to do was to get people to use the land and consider it theirs.’ The Westway Theatre at Portobello Green was duly established by the White Panthers, who were a much less serious version of the Angry Brigade, founded by Mick Farren of International Times and the Deviants. They were meant to be showing solidarity with the Black Panthers, with Farren and the Pink Fairies acting as London’s answer to Detroit’s John Sinclair and the MC5.

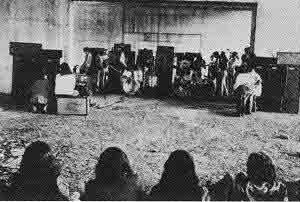

In 1971 Hawkwind played a series of free gigs under the Westway at Portobello Green and Acklam Road, pictured on the gatefold sleeve of their ‘X In Search of Space’ album designed by Barney Bubbles, during which they would merge with the Pink Fairies as Pinkwind. Urban space cadets were invited under the flyover to: ‘thrill to the android replicas, share the cruel sounds of limitless space; co-pilots of spaceship Earth, experts in astral travel, switch all channels through to the void, fill your heads with peace and fire your flesh rockets with the liquid fuel of love, and let us ride together on orgasmic engines to the stars.’ With the proviso: ‘Beware if you fly Hawkwind, there ain’t no return.’ The second Glastonbury Fayre in 1971 was organised by Arabella Churchill, Winston’s hippy granddaughter, from her Revelation Enterprises office at 307 Portobello Road, just to the north of the Westway, featuring Marc Bolan, David Bowie, Traffic, Mighty Baby, Hawkwind, the Pink Fairies, the Edgar Broughton Band and Skin Alley.

Frendz underground paper (the office of which was at 305 Portobello Road) advertised another demo by the Westway with ‘a call to all progressive people; black people smash the racist immigration bill; workers of Britain smash the Industrial Relations bill. All progressive people unite and smash growing fascism. Rally and march July 25, Acklam Road, Ladbroke Grove 2pm. Black Unity and Freedom Party.’ Frendz reported that the 1971 ‘People’s Carnival got off to a joyous start. The street fest continues all this week so do it in the road as noisily as you can… The Notting Hill Free Carnival, a fantastic week of music, theatre and dancing in the street. Everybody got it on and the streets really came alive.’ Pictures of Mighty Baby and Skin Alley playing on the site of Portobello Green were captioned: ‘The weekly Saturday concert under Westway in Portobello Road pounds on. Next week Graham Bond, Pink Fairies and Hawkwind.’ The skinhead fanzine Crunch featured a slice of real life in El Portobello Cafe under the Westway and the Heptones reggae group were photographed by the Westway roundabout.

The 1972 Carnival was organised by Selwyn Baptiste, Merle Major and the North Kensington Amenity Trust, with Merle Major leading a children’s procession from the adventure playground on Wornington Road. Frendz announced that the 1972 Kensington and Chelsea Arts Festival would feature ‘folk groups, theatre, dance, etc under the motorway at Portobello Road where an experimental open air stage has been erected. Also beneath the motorway M40/M41 interchange near Silchester Road W10 will be Groverock! 12 hours of rock music on Saturday June 24 from 12 noon onwards. It will be totally free.’ A Frendz advert for the Greasy Truckers’ Roundhouse live double album, featuring Hawkwind, Brinsley Schwarz, Man, etc, claimed that all proceeds would go towards ‘building a centre in Notting Hill Gate which will be an alternative and cheap rock venue, a playschool and generally just somewhere to go when you’re bored.’

As Pink Floyd recorded ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ and Hawkwind released ‘Silver Machine’, in the summer of 1972 there was a public meeting about plans for the area under the Westway at Isaac Newton School on Lancaster Road. A poster under the flyover advertising the meeting featured cartoons of All Saints hall on Powis Gardens, a bulldozer, a drummer, a man being punched and a hippy saying: ‘All Saints church hall is being pulled down. Perhaps a public hall should be built under the flyover.’ The Acklam Hall would eventually open as the new community centre in 1975, with a benefit gig for the Law Centre by Joe Strummer’s 101’ers. In the meantime there were benefits for the Westway mural project of Emily Young (of Pink Floyd’s ‘See Emily Play’ fame) and Arabella Churchill, at the Westway Theatre. Emily Young recalled: “Under the motorway was just dead cats. People dumped rubbish and nobody cleared it. My idea was to have big archetypal figures and a continuing landscape of hills and green fields to bring a sense of space and freedom to the concrete bays.”

In 1973 Anthony Perry called another public meeting in the Westway Theatre about the doubtful future of Notting Hill Carnival, at which Leslie Palmer came up with the plan to expand the hippy festival into the modern Caribbean Notting Hill Carnival, ‘an urban festival of black music incorporating all aspects of Trinidad’s Carnival.’ The Carnival office under the administration of Leslie Palmer was at 3 Acklam Road for 2 years, and then moved to number 9 in the mid 70s when Selwyn Baptiste became director. As Anthony Perry was helping to establish the Notting Hill People’s Carnival, he was attacked in the People’s News (Notting Hill People’s Association’s newsletter) for getting private business funding for the community projects of the Amenity Trust, ‘set up to develop the land under the motorway for the people in the area’, rather than getting the Council to pay.

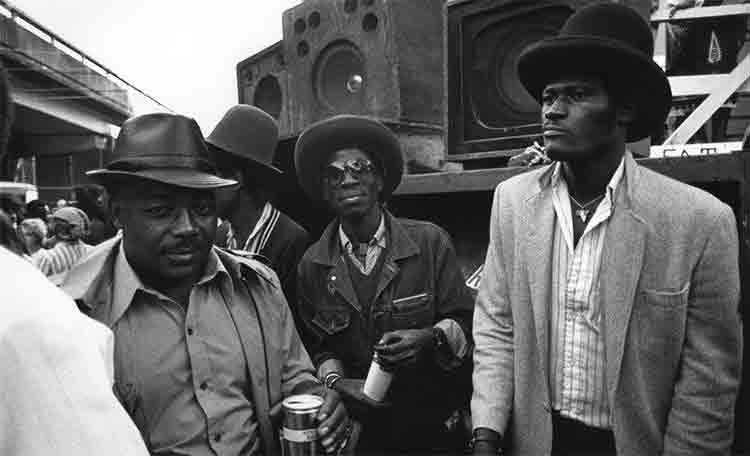

From Acklam Road, Leslie Palmer, Alwin Bynoe and Tony Soares established the blueprint of the modern event; getting sponsorship, recruiting more steel bands, reggae groups and sound-systems, introducing generators and extending the route. The attendance went up accordingly from 3,000 at the beginning of the 70s to 30-50,000. The ‘Carnival ’73 Mas in the Ghetto’ consisted of a festival on Portobello Green with ‘pan on the road from 4pm’; 6 steel bands including Ebony, 6 mas bands including the Ladbroke Grove Jailbirds on Remand, 6 sound-systems and 6 ‘electric funk-Afro-black music’ bands including Black Slate on the corner of St Ervan’s Road. The procession route was along Acklam Road beside the Westway, around Portobello Green, up Golborne Road and down Wornington Road.

In his Carnival memoirs Leslie Palmer recalls his first impressions of the area, Anthony Perry and the trust when he arrived on the scene: “Going to the North Kensington Amenity Trust at 3 Acklam Road offered me the opportunity to observe the derelict state of the terrace, which had been evacuated as they were close to the flyover and faced it directly. The Amenity Trust occupied the end house of the terrace that had been made functional and just about fit for purpose. Beside Cora, his secretary, there was the light skinned Jamaican worker Dave, who Anthony designated to help settle us in. The trust’s work was challenging as they were the most accessible body that seemingly represented the Council and as such they were the target for occasional grouses from disgruntled residents. Their main brief was to ascertain what amenities could be built on the undeveloped land under the flyover. The bays were empty and rubbish strewn but on the eastern side a small playgroup existed across Acklam from the derelict terrace.”

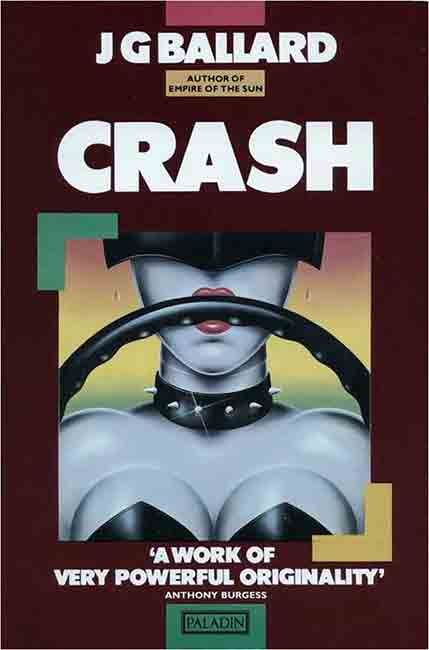

‘Soon after 3 O’clock on the afternoon of April 22 1973, a 35 year old architect named Robert Maitland was driving down the high-speed exit lane of the Westway interchange in central London. 600 yards from the junction with the newly built spur of the M4 motorway, when the Jaguar had already passed the 70mph speed limit, a blow-out collapsed the front nearside tyre… Out of control, the car burst through the palisade of pinewood trestles that formed a temporary barrier along the edge of the road. Leaving the hard shoulder, the car plunged down the grass slope of the embankment. 30 yards ahead, it came to a halt against the rusting chassis of an overturned taxi…’ JG Ballard ‘Concrete Island’ 1974.

After Ballard’s character Robert Maitland crashed through the barrier onto the Westway roundabout and found himself stuck on the ‘Concrete Island’, the next director of the Westway-North Kensington Amenity Trust from 1976 to 2005 was Roger Matland. The motorway also features in JG Ballard’s 1973 novel ‘Crash’, and Trellick Tower influenced his 1975 book ‘High Rise’. Ballard contributed to Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds science fiction magazine, which was at 307 Portobello Road, and Hawkwind had a ‘High Rise’ track. Ballard’s urban myths of the near future would also influence punk rock and post-punk groups such as the Clash, Joy Division, Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, Ultravox, the Human League, the Normal and Mute Records, 23 Skidoo and Grace Jones; most of whom would appear under the flyover at the Acklam Hall. The Westway to the world story of the Clash can be traced back to 1973, when Mick Jones moved to a flat on the 18th floor of Wilmcote House on Harrow Road overlooking the flyover.

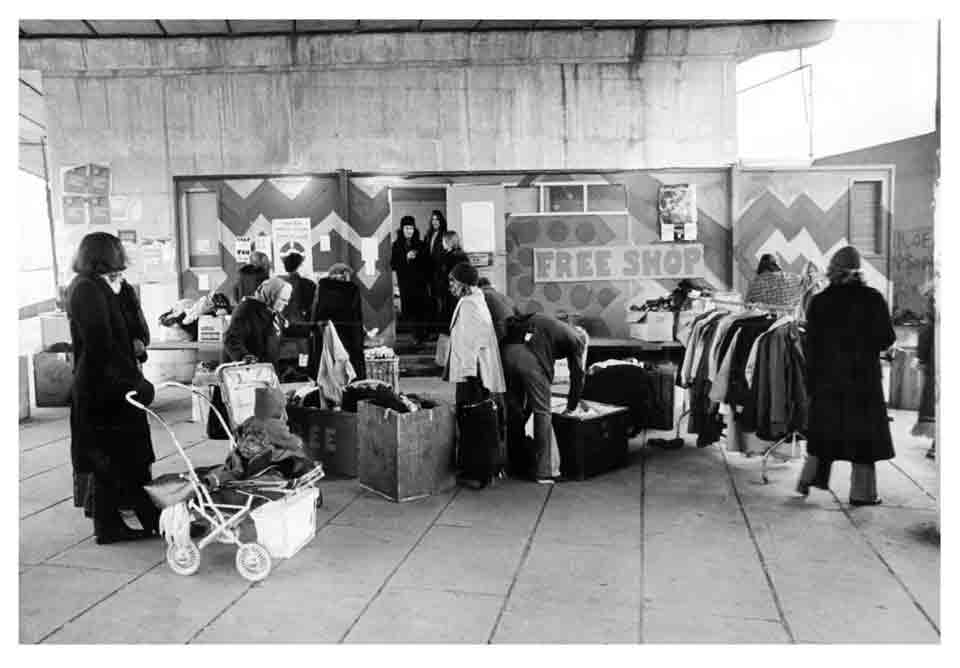

At the time of Ballard’s ‘Concrete Island’ story, Jon Trux’s Greasy Truckers Promotions presented a series of ‘Magic Roundabout’ free gigs, under the Westway roundabout, by Ace, Kevin Ayers, Burlesque, Camel, Chilli Willi, Keith Christmas, Clancy, Henry Cow, Fat City, the Global Village Trucking Company, Gong, Skin Alley, Sniff and the Tears, and Spyra Gyra. Michael Moorcock’s ‘King of the City’ novel contains a report of a Saturday afternoon free gig under the flyover featuring Brinsley Schwarz with Nick Lowe. Moorcock’s Dennis Dover character finds amphetamine rock nirvana with his Basing Street studios session group, playing to an audience of ‘Swedish flower children, American Yippies and French ’ippies.’ Across Portobello from the Westway Theatre a hand sign sprayed with ‘It’s Only Rock’n’Roll’ pointed to the hippy Free Shop proto-recycling centre. Acklam Road in the mid 70s is described by Jonathan Raban in ‘Soft City’ as consisting of: ‘a locked shack with Free Shop spraygunned on it, and old shoes and sofas piled in heaps around it; a makeshift playground under the arches of the motorway with huge crayon faces drawn on the concrete pillars; slogans in whitewash, from Smash the Pigs to Keep Britain White.’

Tom Vague

Post-lockdown, this will be the only history that matters enough, for anyone to want to read. Tony Vague is our Cultural Ethnographer.

Comment by Cy Lester on 23 July, 2020 at 11:36 amWow, what a great article on Westway, took me back to my youth.

Comment by neil houlton on 25 July, 2020 at 5:06 pmGreat article. Wish I’d found this when I was writing my book Roadrunner (Radio On, Road Movies and the A4). Now I’ll have to produce a second edition!

Comment by planktonesque on 13 October, 2023 at 8:28 pm