There’s something heartbreakingly sad when a free-flying bird is trapped in a cage, though even the sky itself has chains. The nightingale, when soaring ‘gainst the wind, high in the heavens, sings the sweetest of songs, as if communing with God Himself. But, when held captive, with blinded eyes, and wings clipped, it’s a poor, voiceless, flightless thing: a blythe spirit degraded by man’s cruel desire to destroy what’s naturally free. My name is Sophie Scholl. I’m twenty-one years of age, and I love life.

I was born on May the ninth, nineteen twenty-one, in the town of Forchtenberg, in the Free People’s State of Wurtenberg. My parents, Robert and Magdalena, were respected members of the local community, and my father was Mayor of the town between nineteen nineteen and nineteen thirty. The fourth child of six, I loved my brothers and sisters with all my heart, and my formative years were nothing less than idyllic. Forchtenberg itself lay on a north-facing hill, overlooking the Kocher and Kupfer Rivers, and the entire town was surrounded by a tapestry of woodland, with an interlaced thread of vineyards. When I wasn’t at school or in church, I was out playing with my siblings and friends, in the sweet-aired, tree-kissed countryside.

When I was twelve, my family moved to Ludwigsberg, and then, two years later, to Ulm, where my father had a business consulting office. I attended the Girls Public School, which was in the process of removing certain books which weren’t approved by the Nazi Party. Teachers, too, were being replaced if they refused to join the National Socialist Teachers League, and an emphasis was placed on physical fitness and sport, rather than mental acuity – none of which concerned me in the slightest, although both my parents were extremely alarmed. During the war of nineteen fourteen to nineteen eighteen, my father had been a conscientious objector, and he’d served his time in the Ambulance Corps. My mother was a lay Lutheran preacher, who stressed the importance of a strong moral and social conscience. It was, therefore, unsurprising that the spread of Nazi ideology was anathema to them. For my part, despite their objections, I joined the Young Girls League – mainly because all my friends did, and I didn’t want to be left out.

When Adolf Hitler became Chancellor on January the thirtieth, nineteen thirty-three, Ulm was one of the few German cities which didn’t officially celebrate the occasion. However, the Nazi Party ‘machine’ duly arrived, in force, and all political opponents were placed in the Castle. Although my father spoke out against Hitler, it was only to us children – and we said nothing, even though we’d been told to inform against anyone who did, even if it was our parents.

At the age of fourteen, and only partly convinced by my father’s concerns, I became a member of the German Girls League. To be sure, it felt wonderful to be involved in a great movement; an equal part of a vibrant congregation of young German women. We went on Summer camps, where we sat round fires, sang ‘Raise the flag’, and told each other folk tales, all the while discovering our great Nation’s history. It was on one of these Summer camps I met a young man called Fritz Hartangel, who happened to be a member of the Hitler Youth, and we got on famously from the start. He seemed decent and sensitive, and we decided to stay in touch with one another, come what may. Although it occurred to me that everything was a form of indoctrination, it was such great fun. Along with the camping, we took part in athletics events, including running and swimming. Most of all, I loved the gymnastics, whether it was tightrope balancing, somersaulting, or formation parading, dressed in pure white slips, with upright members of the Party – erect in more ways than one – applauding every complex move, inspired no doubt by our lithe, muscular young limbs. Looking back, it was all rather perverse, but that didn’t cross my mind at the time.

However, along with the outdoor activities, and a tremendous sense of camaraderie, there were aspects of the League which made me prickle, even when I was appointed a squad leader. We were trained, as a matter of course, to be good wives, mothers and homemakers – roles geared towards the nurturing of future generations of Nazi warriors – as if that was all we girls were capable of. To that end, it was our sacred duty to bear as many children as possible, from both within and without marriage; a morally dubious position, at the very least, and something which, perhaps, gave rise to our nickname ‘The League of German Mattresses’. Worst of all, we were encouraged to rebel against our parents, since the State itself was the only parent we required. Despite our disagreements, I had no intention of defying my mother and father simply at the behest of the National Socialists. I loved my mother for her honesty and integrity; qualities she said she derived from her Lutheran background, although I think she’d have been just the same, even without her beliefs. My father was a well-educated, liberal, open-minded man; a gentle soul, who spurred me to read all sorts of books, to listen to as much music as possible, and to draw and paint whatever I wanted. My parents were good people, and they loved me and my siblings enough to allow us to make our own choices, even when they disagreed with them. I couldn’t imagine, for a single second, the State allowing us any freedom of choice – and if we deviated from the ‘norm’, I was quite sure we’d be punished, although how severely I was yet to discover.

In nineteen thirty-five, the year the Nuremberg Laws were passed, when German-Jews were stripped of their citizenship, I came to realise that, perhaps, my blood was impure somehow; that when I bled, the colours and design of the new State flag weren’t obvious to the naked eye – which surely they should have been, since I was pure German through and through. German blood, after all, was different from French blood, or English blood, or Italian blood, and certainly different from German-Jewish blood, which was tainted from birth. At least, that was the official Party line; a line which most people seemed to toe. As far as I could tell, blood was just blood, and categorised according to its group or type. One’s race or religion had nothing whatever to do with it, and to demonise German-Jews on the basis of haematological fantasy – and all in the name of the Fatherland – was unforgivable. Two of my Jewish friends – friends who’d stayed at my house and were every bit as German as me – were forbidden from joining the League, and I complained to the relevant authorities, but to no avail. All it did was prove I was a potential troublemaker. It wasn’t simply that my friends were Jewish; they were, apparently, less than human, in some ill-defined sort of way: a sub-species, and deserving only of contempt. This, clearly, was a dangerous lie, and one to which I couldn’t subscribe. To compound my troublesome reputation, I read to the other girls passages from ‘The Book of Songs’, by Heinrich Heine – a Jewish writer, whose books were burnt and banned. God-knows why, since they were an essential part of our German heritage, at least as far as I was concerned. The worm was slowly turning.

When my two brothers, Hans and Werner, were arrested and detained in nineteen thirty-seven, merely for belonging to a non-aligned youth organisation, I knew for sure there was something rotten in the State of Germany. It wasn’t that the German Youth Movement was anti-Hitler, since that would have bordered on the insane; it just preferred to be allowed to go its own way, via a combination of outdoor activities and cultural exploration; a mix of scouting and educational pursuit – especially Arts education, with a strong emphasis on German Romanticism. In fact, all youth groups, other than those controlled by the Reich, were proscribed, which was hardly the action of a considerate, respectful parent. More and more, it seemed, Hitler had come to be regarded as infallible; a German Caesar, beyond criticism or reproach.

On leaving the Girls Public School in Ulm, in nineteen forty, with the War in full, terrible swing, and our troops on the march across Europe, I attempted to avoid any kind of National Service, since I was determined not to contribute towards the good fortunes of the Reich. At this point, I had some small idea of the scale of the atrocities being perpetrated against Jews, gypsies, intellectuals and the like, since Fritz, now in the army, mentioned things in his letters to me; things he perhaps shouldn’t have. My own attitude towards National Socialism had hardened, and I’d come to loathe everything that the Fuhrer and his henchmen stood for. The future of Civilisation itself seemed held in the balance, and I had no intention of helping to tip it towards the Nazi regime. To that end, I became a kindergarten teacher at the Frobel Institute in Ulm, hoping it would excuse me from active service of any kind. Unfortunately, it didn’t, and in the Spring of nineteen forty-one, I began a six-month stint in the auxiliary war service in Blumberg, as a nursery teacher. As such, I did my level best not to fill the pupils’ heads with Nazi propaganda, although that was easier said than done. In truth, the best I could manage was a kind of quiet resistance to the State: a non-cooperative way of cooperating.

In May, nineteen forty-two, with my six months of conscience-pricking behind me, I enrolled at the University of Munich, to study biology and philosophy – both potentially dangerous subjects for any free-thinking sceptic: a combination of hard science and deep thought, neither of which were likely to endear me to anyone who swallowed State-sponsored lies. To be perfectly honest, aside from a few quiet voices – voices which included my parents, siblings and a few friends – I felt somewhat alone in my determination to challenge the Nazi machine, since dissent was seldom expressed, and when it was, it was quickly crushed beneath the Reich jackboot. Indeed, my father was currently awaiting sentence, after being overheard by an employee saying that Hitler was the scourge of mankind.

About a month after enrolling at the University, I noticed, during one of my lectures, a pamphlet sheet under my desk. I picked it up, and read:

Leaflets of the White Rose

1.

Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be “governed” without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today every honest German is ashamed of his government. Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes – crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure – reach the light of day? If the German people are already so corrupted and spiritually crushed that they do not raise a hand, frivolously trusting in a questionable faith in lawful order in history; if they surrender man’s highest principle, that which raises him above all other God’s creatures, his free will; if they abandon the will to take decisive action and turn the wheel of history and thus subject it to their own rational decision; if they are so devoid of all individuality, have already gone so far along the road toward turning into a spiritless and cowardly mass – then, yes, they deserve their downfall…

Initially, I was shocked, and rather scared. It was my duty, under the law, to report what I’d discovered, but instead I walked out of the lecture hall, and went in search of my brother, Hans, who was studying Medicine at the University. He’d previously introduced me to several of his acquaintances, and we’d all become very close. Our time together was usually spent hiking, skiing or swimming, and we shared a love of the Arts, and of Theology – especially the sermons of Cardinal Newman, concerning free thought and moral authority. The subject of politics rarely cropped up, but there was something about the words I’d just read which made me think that somehow Hans and his friends were responsible.

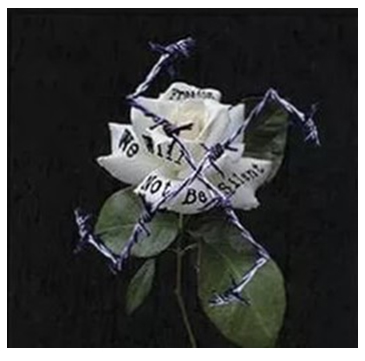

When I arrived at my brother’s rooms, he wasn’t there, so I decided to wait for his return. As I waited, I picked up a book of Schiller’s poetry, and my intuition was confirmed. Hans had underlined several key passages in the book, and on one particular page the exact words I’d just read to myself in the lecture hall. Thus it was I discovered my brother and three of his closest friends – Willi Graf, Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell – were members of an anonymous resistance campaign, opposed to everything the Nazis did and stood for. Since I shared the same points of view, I decided, in a rush of youthful, almost evangelical enthusiasm, to join the group immediately, and the White Rose – a potent symbol of purity – began to fully bloom: a battle between innocence and good conscience on the one side, and the evil of the Nazi State on the other.

During the following month, with my father in prison and my mother ill, we produced two more White Rose pamphlets. If the first one had sought to prompt ordinary Germans into action, by shaming them for their complacent acceptance of an “irresponsible clique”, then the second explicitly condemned that clique – Hitler and his cronies – and, indeed, all of Germany, for the murders of three hundred thousand Jews in Poland:

Hardly anyone even gives them a second thought. The facts are accepted as just that and filed away. And one more time, the German nation slumbers on in its indifferent and foolish sleep and gives these fascist criminals courage and opportunity to rage on – which of course they do.

In the third pamphlet, we spoke of ‘passive resistance’, via the sabotage of armament plants and newspapers, and the boycotting of public ceremonies, in order to bring the Nazi war machine to its knees:

And now every resolute opponent of National Socialism must ask himself this question: How can he most effectively contend with the current “State”? How can he deal it the severest blow? Undoubtedly through passive resistance. Clearly, it is impossible for us to give every individual specific guidelines for his personal conduct. We can only allude to general issues. Everyone must find his own way to realize resistance.

Aware that the Gestapo was doing its best to track us down, we bought the stamps and paper from a number of different post offices, and avoided using University equipment. All of the quotations we collected were copied via a mimeograph, and the finished pamphlets were mailed from all over the city. Although it was assumed that students were most likely behind the White Rose, there was no trail to follow.

In the July of nineteen forty-two, we were forced to interrupt our campaign, as Hans and the others were ordered to spend their Summer break working as medics at the Russian front. My friend, Fritz, had been deployed there a couple of months earlier, and we’d exchanged correspondence. I knew how badly things were going for our soldiers, since, in nineteen forty-one, the Government had organized a propaganda campaign, asking the German people to contribute sweaters, gloves and socks, to combat the cold weather conditions. When Fritz mentioned this to me in a letter, I told him I wasn’t giving anything. “It doesn’t matter if it’s German soldiers who are freezing to death or Russians, the case is equally terrible. But we must lose the war. If we contribute warm clothes, we’ll be extending it.” I think Fritz was shocked by my matter-of-fact response, my clear logic, almost as if it was unfeminine, but I didn’t care. I also knew about the atrocities committed in the name of the Fatherland, since Fritz had witnessed Russian prisoners of war being shot as they stood in graves of their own digging, and he told me, too, of the mass murder of Jews.

While Hans and the rest were away, I was obliged to carry out war duties at a metallurgical plant in Ulm. It wasn’t until November, with all of us returned, the activities of the White Rose resumed. On his way to the eastern front, Hans had passed the Warsaw ghetto, and had been appalled at what he saw. Once in Russia, he became aware that Germany was losing the fight, despite Nazi denials. Fuelled by this knowledge, our activities escalated, and the number of pamphlets increased. As a way of giving the impression that the White Rose operated on a national scale, members of the group travelled across the country by train, distributing leaflets wherever they went.

In the fourth pamphlet, we appealed to devout Lutherans and religious Catholics, assuring them the White Rose wasn’t in the pay of an enemy power. We also made one thing quite plain:

We will not keep silent. We are your guilty conscience. The White Rose will not let you alone!

In the fifth pamphlet, we addressed all Germans:

Do you and your children wish to suffer the same fate as the Jews? Do you wish to be measured with the same measure as your seducers? Shall we forever be the most hated and rejected nation in all the world? No! Therefore, separate yourselves from the National Socialist subhumanity! Prove with your deeds that you think differently! A new War of Independence is beginning. The better part of the nation is fighting with us. Rend the cloak of apathy that you have wrapped around your hearts! Make up your minds, before it is too late… Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the protection of the individual citizen from the caprice of criminal, violent States – these are the bases of the new Europe… Support the resistance movement, disseminate the leaflets!

The sixth pamphlet appeared shortly after the second of February, following the defeat of our forces at Stalingrad. With over a quarter of a million dead Germans on Hitler’s conscience, it was time to point the finger directly:

Our nation stands shaken before the demise of the heroes of Stalingrad. The brilliant strategy of a Lance Corporal from the World War has senselessly and irresponsibly driven three hundred and thirty thousand German men to death and destruction. Führer, we thank you!

We went on:

The day of reckoning has come, the reckoning of our German youth with the most abominable tyranny that our nation has ever endured. In the name of all the German youth, we demand that Adolf Hitler’s government return to us our personal freedom, the most valuable possession a German owns. He has cheated us of it in a most contemptible manner… We have grown up in a nation where every open expression of opinion is callously bludgeoned. Hitler Youth, the SA and SS have tried to conform, revolutionize, and anaesthetize us in the most fruitful years of our educational lives. The despicable methodology was called “ideological education”; it attempted to suffocate budding independent thought and values in a fog of empty phrases. “The Führer’s pick” – something more simultaneously devilish and stupid could not be imagined.

In the light of our military humiliation, a few of us graffitied the words ‘Freedom’, ‘Down with Hitler’, and ‘Hitler Mass Murder’, on the walls of the city hall. It seemed as if the beginning of the end was truly in sight. Obviously it was vital the sixth pamphlet was distributed as quickly and as widely as possible, and to that end, on February the eighteenth, Hans and me packed several suitcases full, and took them to the University. We dropped stacks of copies in the empty corridors for the students to find when they came out of lectures. Just before the break, I realized there were still several left, so I climbed the staircase from the atrium to the top floor, and threw them in the air. It was a wonderful feeling, watching the pamphlets flutter down; subversion in the air – literally. But then I sensed something tremendously cold, as if a shard of ice had pierced my mind. I looked down, and standing there, watching intently, was the custodian of the building, Jakob Schmid: a nasty piece of work, and a fully paid-up fascist. At that precise point, I knew – just knew – we were finished. If anyone at the University represented the Reich, it was Schmid, and he did his duty accordingly. The doors of the atrium were locked, and it wasn’t long before several members of the secret police arrived, and we were dragged off to Gestapo headquarters.

I was interrogated for seventeen hours, and physically abused to such an extent, I suffered a broken leg. Nonetheless, I refused to name any other members of the White Rose. However, it wasn’t too long before Christoph was caught. Whether Hans yielded under pressure, I have no idea, but with the three of us under lock and key, out tormentors seemed content. On February the twenty-second, we were sent for what we all knew was a show trial at the People’s Court, where we found ourselves face to face with Judge Roland Friesler, ‘Hitler’s Hangman’. Everybody knew he was a bully, who enjoyed humiliating all those who stood before him, and I was determined to stand defiant and proud. To begin with, the indictment was read:

“The accused, Sophie Scholl, as early as the summer of 1942 took part in political discussions in which she and her brother Hans Scholl, came to the conclusion that Germany had lost the war. She admits to having taken part in the preparing and distributing of leaflets in 1943. Together with her brother she drafted the text of the seditious ‘Leaflets of the Resistance in Germany’. In addition, she had a part in the purchasing of paper, envelopes and stencils, and together with her brother she actually prepared the duplicated copies of this leaflet. She put the prepared leaflets into various mailboxes, and she took part in the distribution of leaflets in Munich. She accompanied her brother to the university, was observed there in an act of scattering the leaflets, and was arrested when he was taken into custody.”

On the back of my copy, I wrote the word ‘freedom’. And then Friesler began to scream at the top of his voice, accusing us of treason, and threatening all kinds of vile punishment. I realised this was akin to a medieval witchcraft trial, where the woman found herself in the dock, charged with the most perverse form of heresy. At one of the rare moments he stopped yelling, I told Friesler as plainly as I could: “Well, someone had to make a start. What we wrote and said is believed by many others. They just did not dare express themselves as we did”. Unsurprisingly, we were all found guilty, and sentenced to death, by guillotine. I think we’d always been prepared to die for our cause, but the manner of execution was a horrible shock, which chilled me to the bones.

*****

Everything happened so quickly – and in a few hours, I’ll be gone. My cell-mate, Else Gebel, another political prisoner, is very quiet with me. I understand her silence. I told her, on my return from the Court: “It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go… But what does my death matter, if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted?” Else just smiled. She’s always smiling…

I wished. I wished until my bones ached, until my hands and feet ached, until my heart ached, for the power and the strength to cry out against all injustice, all lies, all hurt. I wished for trumpets and drums, to drown out the racket of war. I wished for the cleansing power of creativity, of invention, and of truth, to fill a new world of peace. And I prayed for all people, everywhere, whoever they were, and especially for the young, like me, to grow to realise their full potential.

My name is Sophie Scholl. I’m twenty-one years of age, and I love life.

Dafydd Pedr