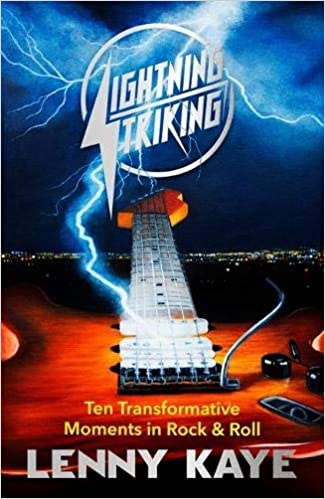

Lightning Striking, Lenny Kaye (£20, White Rabbit)

Lightning Striking is an awesome book: rock & roll incarnate on the page. Although I’m not interested in some of Kaye’s ‘ten transformative moments’ (that’s the subtitle) it’s hard not to get caught up in the descriptions of the music and scenes where they all happen. The book starts with Cleveland 1952, and goes through the 1950s via Memphis, New Orleans and Philadelphia before crash landing in Liverpool in 1962, which is where I started reading.

Thankfully it’s not all the over-rated Beatles, though that’s where it starts. Kaye dives into the Anglicising of Bill Haley, via Billy Fury and Cliff Richard, then steps sideways into Joe Meek’s sound worlds and production techniques. Then it’s back to The Cavern and you-know-who, although to give him his due Kaye contextualises them with other bands on the scene before charting their rise to fame and the American teenage obsession he was part of. Me? I don’t get it at all.

Moving swiftly on, we’re in San Francisco 1967 where ‘The age of psychedelia is upon us’. Drugs, performances, happenings, lightshows, free love and experimental music are the order of the day and it seems Kaye is in the thick of it as composer and musicians attempt to break out of the academy ‘and create “a theater of totality”‘. Meanwhile the likes of Ken Kesey are reinventing literature, the Prankster are playing pranks and the Acid Tests come into being. Meanwhile elsewhere there are different things happening: Brian Wilson in LA is overloading himself and magnetic tape trying to record musical perfection with the Beach Boys, International Times emerges in London, and the 13th Floor Elevators are freaking out in Texas… Kaye swoops back to the Bay Area, noting that ‘If there’s a beginning to the endgame, it is the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park on January 14, 1967.’ This ‘gathering of the tribes’ promises an event spiritual, political and hip, but Kaye questions this, refusing to be too nostalgic, noting that it was mostly ‘privileged young adults who were able to take advantage of the dash for freedom’. Although ‘the concept of Love as universal solution was easily wrapped, packaged and proselytized’, and Haight Ashbury becomes an overcrowded disaster zone as a destination, Kaye points out that something bigger was happening: ‘you didn’t have to go to San Francisco to feel an alternative culture making its mark in the popular arts.’

Kaye, of course, discusses the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone and lots of other stuff that was happening, before consoling himself, and us, with the advice that ‘You can dwell on what didn’t happen. Half empty. Or you can drink the love potion that remains’, although by 1969 in Detroit, where we next land, there isn’t a lot of love potion around. Instead there’s Iggy Pop cutting himself apart, mutated and mutating blues and country, rockabilly and then Motown. There’s also some twisted rock in the form of the MC5 who, according to Kaye, ‘were used to the outer limits of noise, the freedom of a jazz that seemed to have no limits at all, every sound and squeal and rhythmic space in commotion at any given present.’ This was music as revolution, upsetting many listeners both politically and musically, in contrast with The Stooges as a more entertaining freakshow. There are other bands here too, and Creem magazine; and there is a flash forward as the MC5’s Fred Smith will marry Kaye’s future bandmate Patti Smith, and a nod to techno. But we are not stopping, no, we are off to New York City 1975 and London 1977.

Yes, note the order. Kaye doesn’t follow Malcolm Mclaren’s, or indeed any other musical historians’, version of things. New York is where it happened first, where the New York Dolls, Television and Patti Smith invented what would become punk. Where radical theatre and poetry spill out onto the street, where experimental musical performances – be they contemporary classical, early disco, or rap and hiphop – happen in parks, cold empty lofts or basement bars. Where CBGBs is colonised as punk HQ and the Velvet Underground have their real moment as inspiration and alternative heroes. The New York chapter of course sees Kaye at his finest, this is his city, his history; his friends, colleagues, associates and enemies. Here are the musical explorations of Patti Smith turning improvised poems into songs, here is Tom Verlaine reinventing John Coltrane’s freeform saxophone solos as guitar workouts, here is Blondie’s pop punk and Talking Heads’ awkward, tense songs, and the Ramones hit-and-run riffs disguised as blink-and-they’re gone songs.

Meanwhile in London, punk somehow gets labelled as class war and fashion, and recycles pub and glam rock as punk. Mclaren imports the New York Dolls for a second chance and fails, so he creates the Sex Pistols (and later on Bow Wow Wow by stealing Adam Ant’s band). The Clash reinvent themselves as political rebels, but in Kaye’s version of things ‘first the American invasion has to come to town’. As the ripples spread and bands form and organise, ‘there is a moment when everyone looks around and sees themselves, who they’ll be when the lone I becomes we.’ Kaye is astute enough (and has done enough research) to know that whilst the Pistols and Clash remained a focus there were also more original and interesting bands around: he namechecks the Slits, Adverts, X-Ray Spex, the Banshees as well as reggae and Don Letts.

And then there’s another jump, to the later decline and demise of the Pistols, including both their and The Clash’s attempts to storm America, where of course the Patti Smith band are. Kaye notes the arrival of MTV and their requirement for musicians who look good, but also that ‘Punk doesn’t go away’ but lingers on as hardcore. ‘Now there’s a story for another day.’

But instead of that story, we find ourselves in a schizophrenic chapter that is in both Los Angeles 1984 and Norway 1993, a chapter concerning itself with metal, in all its variant forms: heavy, pop and hairy. ‘Hair – that shaggy signifier begins to tease, perm, primp, visit the beauty parlour and salon’, notes Kaye, interestingly suggesting that it is a West Coast version of the UK’s New Romantics. Meanwhile, Black Metal, with its ‘shards of satanic shrapnel’ is summonsed up: ‘Scratch the Scandinavian surface and the gates of hell doth open’; ‘it is Norway that popularized the peculiar sword-and-sorcery that is black metal’s uncompromising howl.’ It’s hard to know whether Kaye really expects us to take this chapter seriously or not. He certainly has a few digs at the poodle-rock elements and doesn’t seem to take the blasphemous satanic rock ritual he discusses very seriously:

Despite its twisted family tree, there is something comforting about the decibel avalanche at metal’s core, the layers of civilization it scrapes away. To unleash our subhuman roar, the primal animal.

Kaye is more taken with grunge in Seattle 1991. Apparently, ‘Everybody’s in a band’, and Kaye suggests that grunge emerges from music created by Husker Du, The Melvins and Green River, that is from punk and hardcore roots, although he doesn’t really convince this reader or himself. He lists known and unknown bands, goes wide to consider New Wave, and also cites REM, before Soundgarden and Pearl Jam take off and everyone buys flannel shirts. Kaye takes a pause for breath and then declares ‘NIRVANA IS THE RUNT OF THE LITTER’, noting that ‘They contain all the bands of Seattle within them, which is why they’re picked from the pack.’ It is not long before ‘IT’S THE WORLD’S TURN to overdose on Seattle’, which of course is what the world did.

But we all know how it ends, how it always ends. Bands implode, singers shoot themselves, critics look elsewhere and the music re-emerges somewhere unexpected. Despite having spent almost 400 pages writing about the past, in lively and enjoyable, immersive prose, Kaye concludes the book proper (there’s a brief ‘Aftermath’ section) by stepping back:

Let’s live in the now. The present, how we experience music, played or received.

This moment, this place. It’s all we have.

But of course, the now is made from the past and is about to become the future. And Kaye’s history is one of the best.

Rupert Loydell