Exploring the disorienting & inspiring openness [1997, remix 2025]

Review: Ocean Of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound and Imaginary Worlds by David Toop, Serpent’s, 1995

by bart plantenga

“the subworld … an environment which registers on our perception at the level of sensation, displaced effect, a suspicion of the other existence.”

- David Toop, “Electric Dreams: Shamanism, Music & Intoxication”

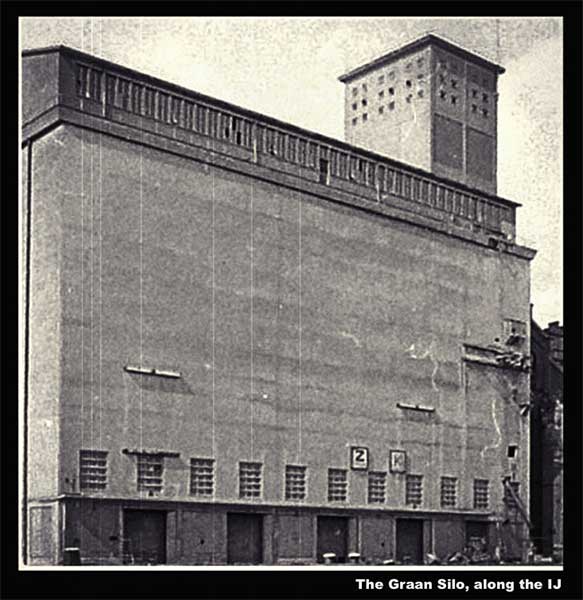

To find the mood I decide to write this piece on set, during the radio show I do on legendary pirate station Radio Patapoe that’s located in the Silo, a giant fortress-like, abandoned granary silo [1896], squatted by artists and punks. It houses studios, a cafe, performance space, living spaces, a radio station, and looms Medieval-esque in an industrial strip in Amsterdam’s Westerdokseiland along the Ij, a lake that most people think of as a river. The front half of this ominous structure just north of Central Station was originally constructed in brick in 1896, to which a monstrous cement addition was finished in 1952. I lived in an temporary Shell office built on stilts in the water in the shadow of the Silo. It was abandoned and quickly squatted by artists in the late 80s. I was offered an office-living-space; my rent was 75 guilders [c. $45, £30] covering utilities and water.

At 3 PM I gather my cassettes, CDs, LPs, buy beer at the Shell station and walk to the Patapoe studio just down the road with an old taperecorder exposed to traffic, headphones on to hear exactly what the machine is “hearing” in the rain – that wOOsh of traffic pushing through rain – “…sound comes from everywhere, unbidden. My brain seeks it out, sorts it out, makes me feel the immensity of the universe…” (David Toop).

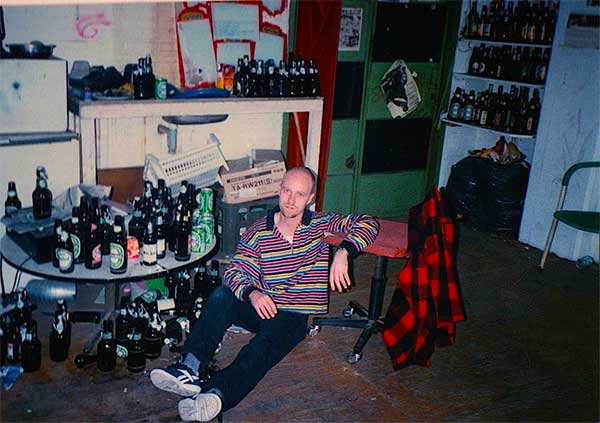

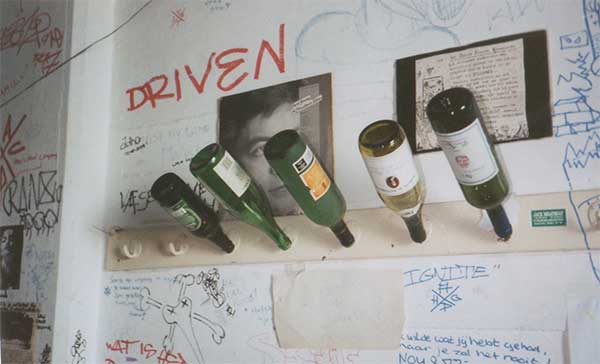

The rusty gate is locked again so I walk to the Silo’s backend, where the cafe is – and water, water in the river, water in the sky and in every fiber of my clothes. There is no way in, until I spot someone in a doorway who begrudgingly lets me cut through the bike stalls so I can balance tipsytoe along the slender cement ledge on the Silo’s riverside to the metal door that allows entry into this musty cavernous shaft. The creak and thud of the door slamming reminds me of Roger Corman films seen in my youth. I climb the 5+ stories up the rickety rusty, taped-up staircase – I think of the belltower scenes in “Vertigo” – “metal phase echoes of footsteps moving along an alleyway, wind in drainpipes …” (Toop) I am reminded of the greasy, musty dust of abandoned factories in derelict industrial zones. I unlock the padlock, enter the studio where every horizontal surface is covered in beer bottles, empty dolmens marking the passage of (festive) times experienced here with an olfactory ambience of flat beer soaked into the album covers of records no one wants to admit they ever liked.

We are in a dank HQ of sound, a crow’s nest full of mangled cassettes, scratched CDs, spurned vinyl, a hand-drawn grid of the Patapoe schedule nailed to the wall. In this regard, Toop quotes Sir Francis Bacon (1624) describing “‘a Sound-House where we practice and demonstrate all sounds and their generation …’”; Patapoe’s equipment is basically held together with hope and duct tape. Some things work: 1 of 2 turntables, 1 of 3 tapedecks, 1 of 2 CD players – but which ones? There’s the mic, with its loose, exposed wire!

DJs must bring their own sound carriers. We do not have a record library except what’s scrounged off the streets… One deck eats a tape right away. I sit down, uncap a beer, put in a tape in the other deck and let it play, and gaze out the window – the tape’s a rehash of an old WFMU show with a new spin – Queen Juliana speeches on turntable II slowed down, backmasked, mixing out of Glenn Branca’s “The World Upside Down” mixed into ocean surf, which blends into Gavin Bryars’ “The Sinking of the Titanic” when – I need to pee (the cold – you can see your breath lay itself down on your cassettes). Its either pee in a bucket in the silo’s main shaft (I look down – a net would MAYBE catch me) that is so pungent with aged piss it gags you while peeing; the open mic in my pocket recording the act. Or I can pee out the window – I’ve done it before and sent me into crazy vertigo, kneeling, shivering in the sill, see “Het Steenen Hoofd” (The Stone Heads), a configuration of old concrete pillars of a pier long ago removed, now appropriated as an official preserve of “art” sitting in the cold Ij. The fade in is the gloomy-hypnotic “Come to the Edge” by Zoviet France.

From another old radio show tape arises David Toop’s ”Bodies of Water” into which I’ve mixed a reverb-enhanced and slowed down Reverend Ike (capitalist Christianity at its baldest) “acccccept whaaaaaat yooooooouu neeeeed” mixed to the point of perfect amalgam; I can’t believe I’m hearing something I have done that makes me smile – perfect mix and totally UNconscious. TSSSH – another beer.

We are here in a subworld, a shared frequency where ghosts of distant voices are heard through headphones; the aural nether where sound grumbles along below sea level, snugly hugging the contours of territory, sound identifying space, the way water defines coast, with great spectral and counterfrictional lassitude, way below the fetishized thresholds of pain, near the edge of all audibility. This is where that subworld’s signature sound (pungent alloy of ephemeral noise, found sound, archival musics, distended rhythms, echo, natural ambience, auto-piloted composition, psychodynamic mood enhancement, and disembodied voices), rumbles along at the somnabulatory frequency of 30 hertz.

Or, as Toop described KLF’s great samplodelic symphony, “Chill Out”, “tuned in to organic and synthetic rhythms normally inaudible to the human ear without radio receivers, hydrophones, parabolic sound reflectors, satellite listening stations … cars roaring across the soundfield … waves on the seashore …” Reverb, a key in this psychoactive ambience, “invokes the sacred…” and can be visualized as a ghostship pushing out its concentric emanating waves. When the waves hit shoreline they fold back into one another to produce a crunched accordion effect of sound, ricocheting from ear to ear – reverb wreaking aural havoc on the stable ear; fomenting dislocation – sound residing both forward and back, as well as inside one’s head (head as drum).

I can see my own breath fall dankly, saturated with grey cement dust – Urban Sax’s “Fractions Sur Le Temps Dans L’Eau”, Hafler Trio’s “Fuck”, Aphex Twin’s “Raising The Titanic”, Gainsbourg’s “L’Eau a la Bouche” – as I remember reading Toop in, I think, The Face, and now The Wire; amazed by how he got away with nerdy erudition in glossies, actually leading readers AWAY from the anxieties meant to stimulate consumption. He should be in “Ethnomusicologia Quarterly” or similar music school library journal. On hisCD “Screen Ceremonies” (Wire Editions/Staalplaat, 1995) he plays all the instruments, paying homage to the places ambience has taken him, tracing arteries on a map of terra incognitas, circling all their genius loci.

All this is subworld music comprised of, as ambienoid, Bill Laswell puts it, “metarhythms…hidden currents,” or what Richard Gehr (Village Voice) called “brain-melting echo,”“in the obscurity of the decibels of the sound systems where dub deploys its magnitude.” (Laurent Diouf, “Octopus”, Paris, Winter 1995.) Toop belongs to this “secret” [in 1997 in any case] enclave of neuronauts, marginal homebodies, hypnoriddimists, soundwave surfers, macrobiotechnicians, and “psychic travellers driven by desire and curiosity” as Hakim Bey puts it in “T.A.Z. Temporary Autonomous Zone” (Autonomedia, Brooklyn, 1991.) who have made of this “landmind” web of data called consciousness a kind of clandestine sanctum of the auditory cortex (near the temporal lobe) where musical sounds can become that phenom called “hearing music in one’s head.”

WFMU, my training ground in the 1980s, is a well-known freeform, listener-sponsored radio station in Jersey City (NY-NJ listening area), where the shrinking American Dream constricts around the necks of the despairing consumer. This is my old radio station, where freeform, that loose association of various music(s) into a more fluid, less categorizable whole, like improvisation, encourages – almost enforces – the incongruous and beautiful meeting of musical forms at that magical intersection, that synaptical and anticipatory instant called the segue. Thus DJs can create an atmosphere (an “auditory dérive”?) where listeners are surprised – sound as Zen satori – to discover new ways of hearing from the collaged infiltration of one sound source by another. This is further encouraged by WFMU’s record library – artists aren’t categorized by style or genre, but alphabetically. This means DJs predisposed to certain kinds of music in their searches come across music they may never have heard before and, as often as not, their curiosity, leads them to wander away from style preconceptions into uncharted sounds thus further encouraging the adventure, the cross-fertilization of genres and cultures. The fact that, for instance, I discovered that both the Swiss people and Aka Pygmies yodel led to a cross-cultural dialogue [and eventually 2 books on the world of yodeling]. This meta-lingual shuffling of disparate sources nudges musical philosophies into a vague cohesive entirety, enhancing an appreciation of the world’s cultures through sound. It’s a proliferation of “new” sound and reconstituted “old” roots – the past becoming ticket to the future, primitive becoming model for the electro-canonical.

Ocean of Sound is the soundsurfer’s guide to sonic waves, perfect for the reentry after you’ve gone so far out. It tells you why you went where in a supremely poetic, idiosyncratic manner, making for jazzy speculative hypertext (it dares to postulate “what-if”), charting streams with endless gurgling tributaries, fountainheads, pools, white noise rapids. When people ask what I’ve done for 11 years as a DJ, I used to say: “just read Ocean of Sound.”

Toop’s main service has been to fuse two disparate streams flowing in seemingly different directions – the “feel good” branch of music verging on the “Muzakal” and the “agony” tributary where Yma Sumac suddenly becomes Diamanda Galas, in what Doris Lessing called “divine discontent.” Toop practicing what Hakim Bey calls “psychic nomadism,” by the “intersecting exterior and interior disturbance” (“The Electronic Disturbance”, Critical Art Ensemble, Autonomedia, Brooklyn, 1994), conjures up the purpose of his book: “… to explore … the path by which sound has come to explore this alternately disorientating and inspiring openness through which all that is solid melts to [the] aether … of the WorldWide Web, waiting to be downloaded, hoping to talk to somebody.”

Toop makes vague claims to community, a kind of fraternal order of neurological astronauts, deep sea divers (the world being 70%, and humans 90%, water) of aural-informational space where old methods for judging culture(s) fall by the waveside; where abandoned factories (or silos) give way to the encroaching jungle and its new inhabitants. A world no longer beholden to standard psycho-economic powerbrokers: “Music in the future will almost certainly hybridise hybrids to such an extent that the idea of a traceable source will become an anchronism.” In other words, “concocting ‘ethnic’ forgeries” (term first used by inventive group, Can) where chanting Buddhists meet sacrilegious Beastie Boys on “Shambala,” where medieval psalms are electronically hybridized, as Hildegaard von Bingen, 12th century celestial scientist and heavenly music composer, so presciently prescribed: “underneath all the texts these watery varieties of sounds and silences, terrifying, mysterious, whirling … must somehow be felt in the pulse, ebb, and flow of the music that sings in me.”

Toop does fine work hammering down elusive music(s) which defy gravity and musical composition but abide the open systems of nature and the Tantra to “hear all sounds as mantras.” Through anecdotal musical anthropology he expands the very notions of ambience exactly while he is giving it shape, dimension and character. As ornithologist, Toops tells us: “The mole cricket digs a loudspeaker-like burrow and then sits inside, rear end airwards, and stidulates, so increasing the amplitude of its song.”

This is circumnavigational poetic scholarship, that strange and inspirational alloy welded by ferociously inventive thinkers who write delightfully and clearly with the aim of a Zen archer – Hakim Bey’s “T.A.Z.”, Mike Davis’ “City of Quartz”, André Breton’s “Nadja”, John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing” – and now Toop’s “Ways of Hearing.”

Toop explores many corners of ambient sound and reports (in the guise of various “-ists and -ographers”) that there’s no single source, no one musical note to which ambient can be traced. Instead he makes a good pluralist’s argument which connects all the liquids – ice, storm clouds, water on the brain, precious liqueurs – into one great acqueous body of mankind – a kind of aural amniotic fluid. This is, in part, aided by the intricate warp and weave of dream diary entries that often fluidly, sometimes awkwardly, carry his personal freight of memory, dream, ephemera, mental effluvia and subliminal sounds along that thin mindstream of astral turf. Toop riffs through music’s secret histories (“… a significant find by Chinese archaeologists: two xun wind instruments, estimated to be 6,500 years old, used as decoys by hunters to attract birds…”) to create a nonlinear evolution of our auditory world through memory (“I have a daughter; she is singing ‘Daisy, Daisy’…Sounds that have remained mysteries for decades”), dream, and phenomenology (“The fizzing drone of a street light.”)

Toop (ob)serves as biographer, bricollager of ephemera, zoologist, oceanographer, geographer, political scientist, psychoanalyst, mythologist, ornithologist and sound aficionado to describe sound as a source of bafflement, healing, community, escape, psychotropic equivalent, and insidious socio-political destabilizer of status quos.

For instance, as an archaeologist, he tells us there have “always” been ambient musics – classical, folk, indigenous – that evoked atmosphere, effectively draping aural tarps over the ghosts of inexplicable phenomena, outlining the unknown. He quotes from a 1992 issue of New Scientist, “‘A scientist member of the American Rock Art Research Association claimed that prehistoric cave-painting sites were chosen … for their reverberant acoustic character.’”

Definition: ambient music sculpts the atmospheric shape of a space. (Think of Dvorak and the symphonic music one associates with high seas adventure flicks starring Errol Flynn, or the Carter Family’s pained-twang harmonies, or Negro prison blues, multi-vibrato Tuvan throat singers, the trance-inducing Master Musicians of Joujouka, the psychic-sonar of Nonplace Urbanfield, the Gyoto Monks’ mantric grunts and grumbles sending shivers and “sympathetic vibrations” down that most “bass-ic” of neurological bass strings – the spinal cord. Or Dutch carillon music swelling the Sunday air with calls to the faithful). Toop in fact, reminds us that Christians appropriated pagan rituals and used music as a charm to ward off misfortune: “With bells being rung to subdue storms at sea…”

Ambient defines liminal and subliminal space, which Toop describes as a “recovery of silence” from the music inside our heads. Or as Toop quotes Thomas Köner, “creator of threshold recordings”: “‘… these sounds that so closely relate to silence transport some of their origins into the music, like a memory …’” Ambient even begins to sound like orgone energy, the vital nonmaterial element that Wilhelm Reich swore permeated the universe. Reich’s orgone box, which he claimed harnessed the healing powers of orgone energy, is not unlike today’s electronic outpost or homebody’s bedroom or chill-out club, or yoga retreat, or zen garden – they all embody the meditative qualities of fountains in the Alhambra. Or for that matter the rivers of static and electro-voyeurism of Robin Rimbaud as Scanner, producer of fascinating “‘field recordings,’” of appropriated private telephone calls, white noise and atmospheric hints of beat. His goal (among others) is to morph prurient voyeurism into a spirit realm that “can also track unconscious desires as they irrupt into the glue of ordinary dialogue.”

As audio archaeologist, Toop describes the “properties of sound – ascribed to pagan forces” which certainly goes a long way toward enamoring me to his irrefutable and “ontological,” assertion that “… the Roman emperor, Nero, attempted to improve his singing technique by lying under sheets of lead and administering enemas into his own back passage. For pleasure, he and his male ‘wife’ enjoyed dressing in animal skins and attacking the genitals of men and women tied to stakes.”

Toop takes up lit-crit’s pen to analyze texts as precursors (or “pre-echoes”) of the trends of our new now. Thomas Pynchon’s Crying of Lot 49 (1966) foresees interactive multimedia ambience clubs: “‘…starting midnight we have your Sinewave Session.’” Toop quotes, “‘that’s a live get-together, fellas come in just to jam from all over the state … We got a whole back room full of oscillators, gunshot machines, contact mikes, everything man.” Toop also finds in J.G. Ballard’s (1971) “Vermillion Sands”, “choro-florists selling singing plants and sonic sculptures growing on the reefs.” This looks just far enough afield to humble trendmongers, and puts interactive multimediaticians and Powerbook cowboys that tout their self-glorifying avantness into a different framework of borrowed ideas and rehashed pasts.

As pop journalist, Toop interviews among others, Sun Ra, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Kate Bush, Brian Wilson, Kraftwerk, and Brian Eno. As early as 1975, Eno wrote blueprints for an ambient music: “‘An ambience is defined as an atmosphere or a surrounding influence: a tint … intended to induce calm and a space to think … it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.’” Like La Monte Young’s Dream House in which sound defines your relation to a space. These revelations seem perfect for our time and are, as Toop points out, “anathema to those who believe that art should focus our emotions, our higher intelligence, by occupying the centre of attention, lifting us above the mundane environment which burdens our souls.”

Eno’s elaborations of, as Toop describes, “insinuating music into chosen environments as a sort of perfume” was a major preoccupation of J.K. Huysmans’ 1884 novel Against Nature in which he imagines a world of mixed media, of Rimbaud’s deranged senses, where the main character “blends musical correspondences with tiny drops of liqueur … fantasizing whole ensembles from the synaesthetic linkage of dry curaçao with clarinets, anisette with flutes, gin with cornets,” to, as Toop quotes, “‘escape from the horrible realities of life’” – art as escapism against a background of highly-staged “total-art spectacles” in the 1890s. This mirrors, in Toop’s eyes, today’s esoteric pursuits of new pleasures and just plain escape through psycho-auditory and pharmacological sensory derangements.

Escapism, is the psychosurgically implanted pacemaker of Tekno (disco + “the human-machine interface of Henry Ford’s assemblyline” in Toop’s words), as it is for disco, punk, ambient, ganja-fed dub, rock & roll, opera, you name it. Escape in the most shamanistic, and yet also, the most facile, convenience-predicated, inept, quick-fix, trend-mongering terms. I believe the human spirit seeks highs like a magnet seeks iron. And I believe if there is a soma (be it laughing gas, ecstasy – the chemical and the religious state – or just oxygen deprivation), a substance, a sacred place, or sound that transforms the dreariness of hanging around all day in your own confined space called the body, then the aboriginal or urbanite will know where to find it. In New York you know which corner, in Amsterdam which coffeeshop, in Jamaica which sound system, in London which club, in Kentucky which moonshine. Like Toop, I believe that kicks and escape are not the same as psychotropic investigation; that headbanging is not exactly the same as incantation or deep meditation but I do believe there is a point where they join the same continuum of effective methods of reality alteration. It’s easy to get too low-brow or high-brow about something like escape (low) or incantation (high). Toop’s anthropological extrapolations of ambient’s mongrel bloodlines eruditely disses (without going either too high-brow or too populist) the mosaic of holy style factions enduring their preferred discomforts as rites of passage into various beat-controlled fad enclaves.

Toop’s investigative enthusiasms also tucks into deep sleep the tired Us-vs-Them notion (most famously exploited by metal-prole Ted Nugent when he tried to buy Muzak, Inc.) that Muzak is THE pernicious mental bacteria infecting our souls. In fact, it is the very boldfacededness of rock & roll as marketable rebellion that has actually become the new Muzak! (Meanwhile, rock music has become the staple Muzak in super markets these days.) Toop quotes a “Billboard” analysis of Muzak to present post modernism in its most gloriously insidious disguise – ”’Muzak has switched…to so-called foreground music (the original hit record by the original artist).’” Rock intent, enshrined in cliché, has become the perfect perpetual youth nostalgia for Muzak’s demographic formatting of enhanced consumerism.

Art historian Toop investigates the visual glum uncles of ambience, minimalists Rothko and Reinhardt et al., (later musically, Reich, Glass et al.) who sought, as Claire Polin pinpointed, “‘to escape into an enfolding quietude from the pressures of a frenetic, discordant world …’” which to Toop is where “music has become voracious in its openness … colonial in its rabid exploitation, restless, uncentered, but also asking to be informed and enriched by new input …” These empty spaces, these synaptic sectors serve as the exposed orifices, the tympanic playgrounds for artists to play in; the deep breathing space where contemplation and invention thrive.

As musicologist Toop reveals his love for music by stringing pearls of insight together so that we are eventually presented with a cohesive if speculative history of music(s). In the chapter, “burial rites,” he manages to string Edgar Varese to Zappa, but also to Jules Verne, the sacred texts of the Mayans, to Charlie Parker asking Varese to teach him structure, and to the exciting (for a dj) notions of “what-if” Varese compositions had been played by Sun Ra or “what-if” the Futurists’ notions of noise had been incorporated into Stravinsky’s “Le Sacre du Printemps”.

In the section “content in a void” Toop’s creative speculation becomes poetic elation, convincing me that biographies of such complex characters as Dean Martin and Howard Hughes reveal lives of “weird, hermetic, formless existences” which coincides with elements of ambience. This allows Toop to make the case for the true tension of modern life in terms of musical atmospheres: “disquiet hovers in balance with the act of escapism or liberation. That tension between the specifics of the soul and the siren call of the oceanic…” That pulsing hum of “9 1/2 Weeks”, “Miami Vice”, Bryan Ferry, Diva, Grace Jones, “Blade Runner” – ”atmosphere as style; style as mood…” This allows him to couple Bono with Sinatra at their duet: “I‘ve Got You Under My Skin” “where beneath the gloss of celebrity … were distant, unspoken connections between a realm of ambient, electronic experimentation and the nice-and-easy-does-it domain of supper-club Las Vegas…” Which really gives Baudrillardian resonance to that late 90s bifurcated concurrence – new and nostalgic or “lounge” as granddad’s chill-out room.

Toop relates how Hendrix dreamt of working with Rahsaan Roland Kirk; how Hendrix came within a few months of working with Miles Davis on “Bitches Brew”. Davis was listening to Sly Stone, Hendrix and James Brown and, with the guidance of Paul Buckmaster of the obscure Third Ear Band, “investigating the music and theories of Karlheinz Stockhausen.” Toop’s bio-speculations amplify the notion that as we grow closer together and familiar as humans we grow equally distant and alien, “trying to replace alienation with techno-spirituality, using contradictory messages to express confusions for which our history has not prepared us.” A post-modern tautological malaise; spiritual aetheists in search of new isms to conquer with smug cynicisms.

The recording studio is where idiot-shaman music producers perform this uneasy contradictional surgery between aether and metal, speculation and sound, well-being and angst. Third world roots, indigenous, and organic communiques get downloaded by psychotropic acousticians on electro-prosthetic mixers to extrapolate and amplify the neural-organic sound for the 21st century – producer as ambassador, Albert Hoffman, anthropologist, surrealist. Because, as Toop puts it, “The imagery of altered states, along with the desire to travel through intangible dimensions … to float and be intoxicated by rhythm and frequencies are central to the force of music.” I think of how Jon Hassell’s muted trumpet could be heard “mindsweeping” the inner-atmospheres. The faders, knobs, and microchips serve in the roles of LSD-like psychotropically-drenched cells in synaptical space, the subworld, where musics are destratified, defactionalized, genre-obliterated and engaged in inveterate play where the tangible becomes substanceless, boundaries and aesthetic prejudices blur, become liquid, liberated from the mind’s “material matrix” as paleontologist-theologian, Teilhard de Chardin once described it.

In “altered states iv: machine” Toop refreshes our memories of that mid-80s cultural cross-polliination of hiphop kids breakdancing to Kraftwerk while others retooled Kraftwerk’s “Man Machine” to make dance music that was already dance music. And how Kraftwerk defined hot by being cold. The tension between flesh and steel, emotion and logic. “Anticipating the deification of sporting speed stars … the fetishisation of communication regardless of content … the destruction of homes to make way for roads …” Meanwhile, 70 years earlier, Erik Satie who “lived like a machine” pre-saging Kraftwerk, as well, presaged the industrial music of Einstürzende Neubauten by composing music “in 1917 for ‘Parade’, a ballet collaboration between Erik Satie, Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso and Léonide Massine, [where] Satie scored for typewriter, pistol shots, steamship whistle and siren alongside more conventional instruments …’ which expressed’” as Toop quotes James Harding, “‘both the ugliness of a mechanical, commercialised age, and the spirituality that is crushed beneath it.’” John Cage learned his own essence from how Satie’s “work explored extremes of simplicity or repetition” and how “Satie’s jokes invariably concealed a serious purpose.”

Anthropologist Toop relates how Balinese gamelan music, which totally mesmerized Antonin Artaud in 1931, infilitrated the musics of many of today’s greats: Don Cherry, Gavin Bryars, Harry Partch, et al., even recent ambient dubsters, Loop Guru, noting that this music’s “‘pleasant and delightfull’” ambience was documented as long ago as 1580 by buccaneer Sir Francis Drake! Leonard Huizinga (1937) in describing gamelan’s effects, could easily have been describing chillouts or all-weekend raves: “‘This music does not create a song for our ears, it is a “state”, such as moonlight poured over the fields.’” Extended – sometimes for days – gamelan performances “as a kind of ambience.” Toop further extrapolates an important cultural connection by placing Claude Debussy at the Paris World Fair in 1889 where he heard gamelan music with its watery themes which could have been important in Debussy’s many watery themed works: “La Mer,” “Jardins sous la pluie” ... These javanese themes, to Toop suggest HIS own raison d’etre when they, “suggest an emergence of dreams and unconscious desire into the tangible world …” Debussy’s “drift into unknown sound zones” has led to the “Increasing numbers of musicians … creating works which grasp at the transparency of water … moods and atmospheres, rub out chaos and noise pollution with quiet … avoid form in favour of impression …”

We see Toop floating down the Orinoco River on his psycho-pharmacological-mental-time-dilation expedition (“the journey seems to take ages”) into the tympanic membrane of darkness where Toop in post-modern situ – he’s reminded of “Apocalypse Now” – tries to confront the dandy’s version of “Aguirre, The Wrath of God” inside him, the nature of curiosity seen floating on the river. He seeks, in no small way, the confluence of all his concerns – where and how memory, dream, psychoactive drugs, ritual, shamanism, travel, water, sound, beauty, terror, sensory deprivation and overload come together. A daunting mission but Toop pulls it off, risking a hoot and snicker here and there. He floats into the mouth of the river to declare: “…we return to the sea for a diagnosis of our current condition. Submersion into deep and mysterious pools represents an intensely romantic desire for dispersion (Natalie Wood, Robert Maxwell, Hart Crane, Dennis Wilson, Ray Johnson …) into nature, the unconscious, the womb …”

As I lived ON the water for 1.5 years, with water literally lapping up underneath my floor, through pillow, into my innermost ear, I took all this to heart. In fact, “scientists have discovered that your stapes bone in your inner ear emits a drone …” (Listen to “A BoneCroneDrone” by Sheila Chandra.)

Maybe music’s role is to harmonize this internal drone with external ambience; a symphony of interior and exterior signals, to make all collective, connective. As Toop quotes Theodore Schwenk’s “Sensitive Chaos”: “‘Through watching water and air with unprejudiced eye, our way of thinking becomes changed and more suited to the understanding of what is alive …” I am sure that when I catch myself “fishing in the dark” it will be in efforts to catch some bigger fish from some ever deeper subworld.

~~~

- This is a significant remix of the article that originally appeared in the January 1998 issue of AMERICAN BOOK REVIEW

- David Toop’s interview with composer-eventsmaker Charlie Morrow on iMMERSE! addresses the immersive state in music, architecture, literature, & atmosphere: https://immersesoundlightspace.podbean.com/e/david-toop/ .

- Many of my Wreck This Mess radio/mixcloud soundscapes utilize, borrow & wallow in the ambiences touched upon in the article: https://www.mixcloud.com/wreckthismess/ .

- about Zoviet France, silence & seclusion in the South of France: “Shouting at the Ground” https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/shouting-at-the-ground-through-the-trees-by-bart-plantenga .

Really interesting article, thank you.

Comment by Rupert on 27 September, 2025 at 7:55 amFantastic to see this alternative world that also is filled with sound.

Comment by Black Sifichi on 12 October, 2025 at 9:45 am