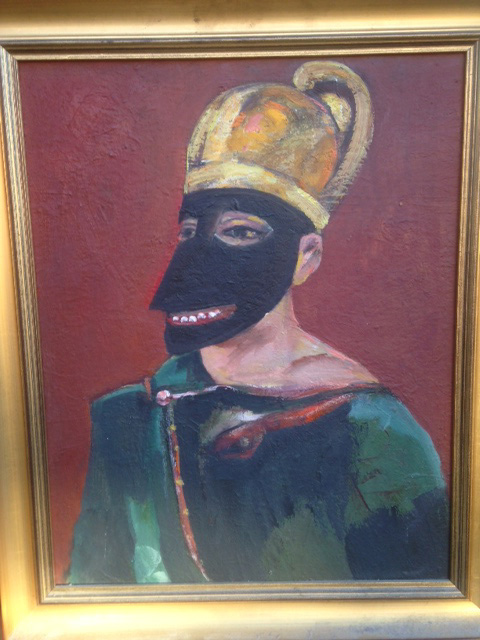

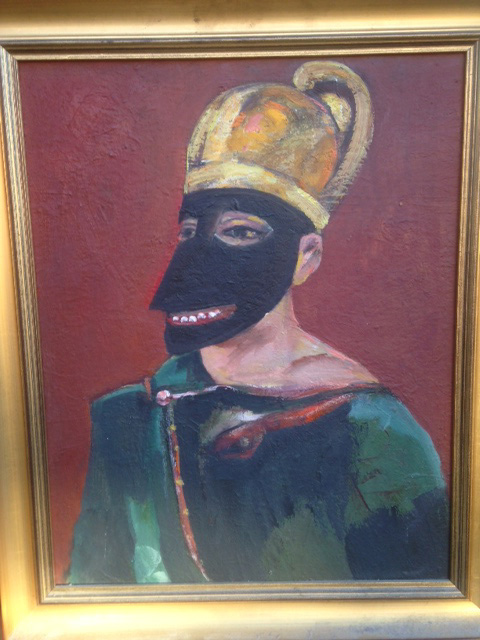

Doge Marino Falieri date unknown.

Stanislaw Frenkiel.

Synopsis

The story spans a day in November 2010, as the final preparations of a major retrospective of an aging painter are underway at Tate Modern. The private view; a jamboree of press, critics, celebrities and sponsors (even Tony Blair, a friend of the sponsor, is expected) takes place that evening, and the painter, Mateus Stefko, whose life has been blighted by war, secretly plans to make a citizen’s arrest. He becomes attached to a young art handler, Jerome, unaware of Jerome’s past in the care system, and who was helped into art school by Martha, a charismatic art therapist who had strong unconscious feelings for him. As Stefko and Jerome check the final hang, the paintings trigger Stefko’s memories:- pre-war Krakow, POW in the Soviet Union, cosmopolitan Beirut and eventual arrival in the UK. When they reach Untitled, a portrait of a partly dressed, masked woman, Stefko reflects on the intense relationship he had with its subject – Martha – whose hour by hour agonizing about whether to accept Stefko’s invitation to the opening is spliced into the unfolding story at Tate Modern. She hasn’t seen him for thirty years. Jerome’s story meanwhile is told in flashback, with the mysterious Martha at the heart of it. Neither Stefko nor Jerome know of her existence for the other until the denouement that evening in front of Untitled. This private drama is offset by a very public one, as Stefko waits and watches for his prey.

The novella is about how making art can deliver emotional salvation, as well as the relationships between the main characters, and how war has affected their lives. Dedicated to Stanislaw Frenkiel – 1918 – 2002 www.frenkielart.com. This is a fictionalised account of his life but the paintings described in the text and reproduced here are real. The tale will unfold week by week, through Stefko, Jerome, Martha and the paintings.

7pm

Tate Modern

I can’t read her letter here, thinks Stefko, patting his pocket, to make sure it’s still there. He is surrounded by a holy trinity of Eva, the Director, and a famous critic – Hannibal on the wall behind them. The painting also seems to be waiting, the vast elephant and its rider as patient as ever. Soon, soon. Before I get drunk.

‘Where’s Blair?’ asks Stefko, raising an eyebrow.

‘He’ll be here presently,’ purrs the Director, looking at his watch.

‘Good,’ says Stefko, straining now to look for Martha. I want her to see my citizens’s arrest.

Moving through the crush of the room, Martha spots Matt in front of Hannibal speaking excitedly to a group of people who have no idea of the recent small drama. Small? Is it small to hit someone in a public place? Hit someone anywhere? She doesn’t want to intrude, so sits – a little too heavily – on one of the square leather sofas, spilling some wine. Stefko catches her eye. Later, he mimes, looking rather red, prodding at his wristwatch. As he returns to the intensity of the conversation Martha watches an elderly woman put her hand on the small of his back in a gesture of affection rather than ownership. Yes, this will be Eva. Martha studies her. She’s taller than him, and dressed like an elderly hippy in her orange kaftan. Her russet hair clashes with it slightly, and her glasses are over large. But she carries herself well. How she used to resent her, cherishing Matt’s complaint she doesn’t understand me – or my art.

But I do Matt. I do.

Eva seems to understand him perfectly well now, as she tenderly strokes his arm. Like most mistresses Martha had conveniently forgotten that her rival (her rival?) was an accomplished woman. A psychiatrist – or something.

Stefko, his colour high, gulps at his wine. He knows that Martha is looking. Flourishing a hand, he gestures to her to stand, and walks over with Eva. ‘Meet Martha my dear, a student from the past.’

And Eva, smiling, looks her in the eye and offers her hand. ‘I have heard a great deal about you.’

‘Yes?’

‘Yes,’ echoes Eva looking sweetly maternal. ‘He only ever talked about the talented ones.’

He talked about me?

And then Eva’s clipped cry as her husband claws at his shirt, and falls. It is if a bullet has struck. The sound of Martha’s glass shattering on the floor seems louder that the shouts of ‘help’. A young woman in ripped jeans and a bowler hat emerges from the crowd.

‘I’m a doctor,’ she declares, undoing Stefko’s tie, pulling at the collar of his shirt, buttons popping. Eva sinks to her knees beside him. ‘Kochanie, Kochanie, Mateu.’ Martha hears her cry, then, in distress of her own, watches her take his hand.

Stefko’s mouth is turning blue. The doctor forces it open.

‘What are you doing?’ says Eva, ‘you shouldn’t do mouth to mouth these days.’

‘Checking he hasn’t swallowed his tongue,’ the doctor replies calmly.

‘Of course, sorry, sorry.’

Martha imagines it rolled back in his throat, curled around the words still unsaid to her. She steps forward, to reach for Matt’s other hand, but freezes, to defer to the wife: for both are hers to take at this terrible moment. Martha returns to the edge of the crowd, churning like restless cattle – the edge, where she’d always been in his life. The famous critic is agape, the Director waving one hand wildly, the other clamped around the phone at his jaw. Martha stares at the young doctor, who is lifting one of Matt’s eyelids – showing the whites of its eyes, like an animal. How he’d hate this indignity, thinks Martha, desperate in her helplessness.

‘Airways, breath, circulation,’ mutters the doctor in a mantra of professionalism.

‘I feel no breath,’ says Eva, the back of her hand at his mouth.

The doctor turns to the crowd, ‘don’t stand there gawping, get an ambulance.’ But someone already has – for Martha hears its faint wail underneath the commotion. ‘It’s a cardiac arrest,’ says the doctor, ‘we need to keep him warm.’ But Eva’s kaftan is already off as she spreads it over the body of her husband of sixty years. Martha closes her eyes in deference to the gesture; its love.

The young doctor presses the heels of her crossed hands into Matt’s chest. It looks as if she’ll break his ribs, but the hands bounce back. Martha wants to laugh at Matt’s feet in the old hushpuppies flopping aside like a clown’s. Why is tragedy often so comic? She thinks. Nature’s way of staunching pain? The doctor presses again – Martha unsure if she is forcing life in or death out – and checks again for a breath. ‘None,’ she says swearing softly to herself. Then more pressing – the doctor’s crossed hands mimicking a heart knocking at the door of Stefko’s own, Eva encouraging him in a series of soft Polish consonants. The medics are here now with some apparatus, which they fix to Stefko’s face making him look like a giant insect. ‘How long has he been like this?’ asks one.

‘Two and a half minutes,’ says the doctor checking her watch.

‘Exactly?’

‘Pretty well.’

‘Then he may have a chance.’

‘God. Please God,’ intones Eva, unable to say good-bye to him here – in public. The defibrillator is applied, strands of grey chest hair curling around the paddles.

‘Shame’ shouts Martha, as mobile phones are pointed – covertly of course, for an art crowd would never behave like this. Would they? But anything goes these days, and Matt’s death could be seen as the ultimate post-modern performance. ‘Come on, let’s show some respec’, growls a security guard, clearing a path through the crowd. ‘Or I’ll ‘ave those phones off you.’ Martha, in her distress, notes the residual decency of the working classes.

Stefko’s mind is floating. His pain over, he is free to feel the bliss of passing through a dark red tunnel. Birth – and sex – and death; the same red walls. He feels his body now as a young man, moving in his prime towards a light at the end, which is getting brighter, bigger. There are shapes, which he sees as faint figures, then faces encouraging him to move towards them. There is Mama – looking exactly as she did the day he said goodbye to her. Look, Anton in his prime, swigging whisky. Whisky? In heaven? Of course there would be whisky in heaven. He feels wonderfully happy as he moves towards them. He swears he sees his old teacher Georges Rouault. The faces get bigger.

He knows he shouldn’t look back, but he does. At himself covered in orange cloth, being rolled onto a gurney, a medic holding the mask. As he’s wheeled through the room the light of the surrounding paintings reach him like equidistant suns. Eva is at his side. Dear Eva, at least we had a happy evening yesterday. You made hunters’ stew – and we’d drunk Vodka together. Ice cold. He sees Martha, distraught, her fists in her mouth. Well Martha my love, at least I’ve seen you and I am no longer around to mess up your life with longing and memories. You can now archive me. Get some pictures up. The only thing I’d have left Eva for would have been a child. And that would have broken her heart. Take care Martha – I loved you very much.

The gurney is at the door now, by it a cluster of anxious looking people – at their centre a nervous looking man in a dark suit and white open necked shirt, emphasising his ridiculous suntan. The Director springs across to speak to him, the man and his entourage, for once, not the centre of attention. There is vigorous nodding and speaking into phones. Stefko turns once more to the light. Is old Rouault still there? My God he is. His feelings are ravished as the face of the old devil joins the others. Then he looks back again, into the room and its commotion, Blair nodding gravely, the Director speaking, almost yapping at him. And then at the doctor, who has put her hat back on. That must mean that I am dead, thinks Stefko. But he listens all the same.

‘Is he dead?’ Eva asks the doctor.

‘The defib’ may have helped, got some blood to his brain.’

Blood to my brain?

‘The next hour will be crucial,’ says the doctor. The faces at the end of Stefko’s tunnel smile and turn away. His journey reverses. ‘Where are you taking him?’ asks Eva through her tears.

‘Coronary unit at St Thomas’s. Over the river,’ hears Stefko.

Ha – across the Styx, the other way. And Stefko’s heart beats once more in rebellion, pumping blood that has not yet cooled.

Martha starts to follow his body. She must retrieve the letter. Eva must not find it. But there’s nothing she can do about that now, as Matt is wheeled off, towards the lift and the waiting ambulance outside – Eva at his side. Martha turns, to try and find Jerome, to tell him what’s happened, that Mateus Stefko appears to be dead.

Jan Woolf

Untitled: A Novella is being serialised each week on International Times

.