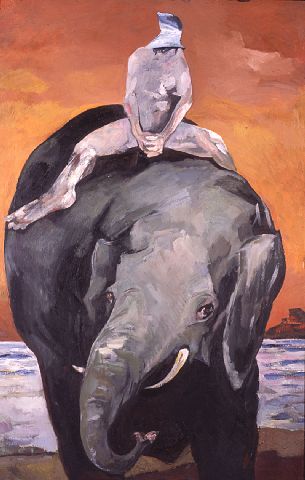

Hannibal – Stanislaw Frenkiel 1969

Synopsis

The story spans a day in November 2010, as the final preparations of a major retrospective of an aging painter are underway at Tate Modern. The private view; a jamboree of press, critics, celebrities and sponsors (even Tony Blair, a friend of the sponsor, is expected) takes place that evening, and the painter, Mateus Stefko, whose life has been blighted by war, secretly plans to make a citizen’s arrest. He becomes attached to a young art handler, Jerome, unaware of Jerome’s past in the care system, and who was helped into art school by Martha, a charismatic art therapist who had strong unconscious feelings for him. As Stefko and Jerome check the final hang, the paintings trigger Stefko’s memories:- pre-war Krakow, POW in the Soviet Union, cosmopolitan Beirut and eventual arrival in the UK. When they reach Untitled, a portrait of a partly dressed, masked woman, Stefko reflects on the intense relationship he had with its subject – Martha – whose hour by hour agonizing about whether to accept Stefko’s invitation to the opening is spliced into the unfolding story at Tate Modern. She hasn’t seen him for thirty years. Jerome’s story meanwhile is told in flashback, with the mysterious Martha at the heart of it. Neither Stefko nor Jerome know of her existence for the other until the denouement that evening in front of Untitled. This private drama is offset by a very public one, as Stefko waits and watches for his prey.

The novella is about how making art can deliver emotional salvation, as well as the relationships between the main characters, and how war has affected their lives. Dedicated to Stanislaw Frenkiel – 1918 – 2002 www.frenkielart.com. This is a fictionalised account of his life but the paintings described in the text and reproduced here are real. The tale will unfold week by week, through Stefko, Jerome, Martha and the paintings.

Part One

November 10th 2010

7am

Tate Modern.

‘Kto est jest?’ whispers Mateus Stefko, as he shuffles towards the young man squatting by the wall. ‘Ah,’ Stefko breathes into English, ‘a technician’. The technician, or art handler as he’s called these days, folds his spirit level, stands, and dips his head respectfully. ‘Morning Mr Stefko.’

‘Good morning young man, your name?’

‘Jerome.’

‘Please call me Matt,’ says Stefko, attempting to click his heels. But old Hushpuppies don’t click. He holds out a trembling hand.

Which Jerome takes in his own, wondering at the cool papery feel of it – how he still manages to paint. He looks into Stefko’s famous blue eyes, like creatures in a rock pool under the wire rimmed glasses. That hedge of white hair is surprisingly thick and springy for a man his age, his jowls hardly dragging at his mouth.

‘What is the matter with those two?’ Asks Stefko, thumbing backwards over his shoulder, where two paintings face the wall as if being punished.

‘Just back from the Elephant,’ answers Jerome looking around for colleagues. But they’re hard at work; Otis the paper conservator arranging sketchbooks in the Beirut room, Karl and Jasvir finishing the hang in the river rooms where a curator is strutting around like a stork. ‘Elephant?’ barks Stefko taking a sideways look at Hannibal, the painting ready to be hung. The blindfold warrior’s dunce’s hat sits low on his brow, his naked body as pink and vulnerable as a prawn, his legs splayed over the beast’s grey mass; clasped hands protecting his balls. ‘What elephant?’

‘Tate Modern’s quarantine store at Elephant and Castle Mr Stefko.’

‘What in Gods name is that?’

‘The place old paintings go to be checked for disease.’

‘Diseased paintings? How thrilling, what was the matter with them?’

‘There were moth eggs in a canvas.’

‘I see. Which one?’

Jerome searches the various pockets of his jeans, and Stefko makes a quick study; I’d paint you with a touch of cadmium yellow in the skin to emphasise your blue eyes, some green in your hair to highlight the brown. I would ignore the – what do they call them? freckles? frackles? Too childish in a boy as good looking as you.

Jerome retrieves a piece of paper, ‘river…’erm, Vist…’ he attempts, reddening.

‘River Vistula in the Winter,’ supplies Stefko, ‘and the other one?’

‘Eva, nineteen forty.’

‘Eva? Yes. Yes?

‘Had wood-worm in the frame’

‘Ah, nineteen-forty,’ sighs Stefko, thinking of the Eva of twenty-ten, hanging on in there, like himself.

‘Your wife?’ asks Jerome, wondering if this was too personal, and reddening again.

‘Yes, immature and sentimental, both of them.’ Stefko’s grin reveals a gap in uneven front teeth. ‘Paintings, not wives,’ he adds. ‘But early work is always required for major retrospectives – no?’

‘Sure.’

‘Starting my show at nineteen-forty gives a sense of…’

‘History?’

‘No, reach,’ snaps Stefko. ‘I have had a long painting life, not like old Gauguin who started late and got venerables disease.’

‘Don’t you mean…?’ Jerome hesitates, maybe that was the right word.

‘Tell me, did they allow the moth’s eggs to hatch?’ asks Stefko, imagining moths flying out of a wintry sky.

‘They poison them.’

‘A poisoned landscape? Fascinating. But I am delighted they caught Eva’s worms.’

Jerome smiles, warming to the old man, ‘I understand you wanted a chronological rather than a themed hang Mr Stefko.’

‘How else would a retrospective be?’ snapped Stefko. ‘I do not have themes, I have obsessions. And I told you to call me Matt.’

‘Doesn’t it depend on the curators? Matt?’

‘Bloody curators,’ grumbles Stefko, scratching his cheek. ‘They train the creatures these days; leech all the intuition out of them. There’s a whole coven of them here – even a curator of…?’ Stefko flaps his hand disdainfully, ‘interpretation.’

Jerome grins, thinking of the intense young Asian guy with the shaved head.

‘So Jeremy’ says Stefko, ‘what happens to Eva and the Vistula now that they are healthy?’

‘They stay on their foam blocks for the rest of the morning.’

‘Foam?’

‘It’s part of the risk assessment. And my name is Jerome.’

‘What?’

‘JerOME.’

‘I see. Why?’

‘All paintings have to rest on foam blocks to acclimatise them for the space.’

‘You mean a wall JerOME,’ says Stefko rolling his eyes at the ceiling. ‘The neutralisation of meaning by you English has always annoyed me. I suppose you call my paintings images – no? And I am a painter NOT a practitioner.’

Jerome smiles softly at the old man. I, Jerome Carter, am also an artist.

‘I stretched those canvases as a student in nineteen thirty seven,’ says Stefko, ‘attacked them with builders’ brushes, scraped the life in and out of them with palette knives,’ He pauses for breath. ‘And now I must sit down.’

‘Sure,’ says Jerome, clearing a grey plastic chair of his drill and spirit level. ‘Thank you.’ Stefko settles into the chair. ‘Those frames – on which worms have feasted – were made out of old furniture found in the street in Krakow. They weren’t treated so kindly then, nor when they were thrown in the back of a cart to get them out of Poland after the war. Foam blocks indeed. Risk assessment. Ha!’

Jerome smiles, realising that his art history lectures had just come alive, that this time spent alone with last of the great European Expressionists will feel precious one day. He glances at his watch. Hannibal is not yet hung, the Director has only just agreed to let Stefko have his poem next to it; not yet printed, let alone grafted onto the wall. The Triptych isn’t straight and they still have no idea where to hang Untitled. The morning will soon be gone and they’ll start falling over the caterers.

‘I am ancient Jerome,’ grumbles Stefko, who’d noticed the glance at the watch.

‘Yes, ninety, your dates are on the wall.’

‘And foreign, I have never felt so bloody foreign.’

‘Mustn’t use the eff word these days – Matt.’

‘I’ve had British citizenship for sixty years and I can say what I like so don’t give me that political correction shit.’

‘I think you mean politically correct.’

‘That is what I said,’ said Stefko, pointing at Hannibal. Do you know who that represents?’

‘‘erm Hannibal?’

‘No, I said represents, not IS.’

Jerome shrugs.

‘Your Tony Blair.’

‘MY Tony Bl…’

‘Mateus…Matt!’

They turn their heads together like a pair of meercats. A young woman in jeans, a mobile phone clamped to her ear, walks vigorously, almost runs, across the room. ‘Oh, Jenny,’ announces Jerome, reddening again.

‘Who? asks Stefko, admiring the black bob, long legs and full scarlet lips.

‘Jenny, media officer.’

‘Good lords I forgot,’ says Stefko, theatrically pressing the heel of his hand into his forehead.

‘Are you ready Matt?’ asks Jenny, her head coquettishly to one side.

‘It’s Mr Stefko’ snaps Mr Stefko, thinking her like a minstrel from one of Giotto’s later works. ‘Mr Stefko, so sorry,’ she replies, blossoms of pink forming on her cheeks.

‘I have to go and speak to the radio,’ says Stefko, slipping his arm into Jenny’s.

Bit familiar, considering he’s just insulted her, thinks Jerome, watching them walk off like a carer and her ward.

Jerome turns to the painting waiting to be hung. Hannibal – looking as if he’ll slide off his elephant and go home if he isn’t up soon. The painting unnerves him: that arrogant figure astride something too big for him ‘Yeah, Blair,’ he says to himself. ‘Cunt,’ he says, as he hoists it onto the wall.

Jan Woolf

Untitled: a novella is being serialised each week on International Times