1

.

While international headlines were bruiting Daesh bombings in Baghdad last week, a very different story was unfolding south of the capital in the historic region of Babylon, a story of culture vs. barbarism, in which I found myself playing the small but important part of contributing a 15-minute poetry set.

.

The Babylom Festival of International Culture and Arts was commencing its week-long schedule on Fri 13 May, just two days after the Wednesday bombings that had killed 100 people in Sadr City and around Baghdad. In London, I wondered if the organisers would cancel, or whether I should. An email appeared with the latest information about tickets and visas. The show was going on. I wasn’t worried about the Friday 13 date; that was Templar superstition.

.

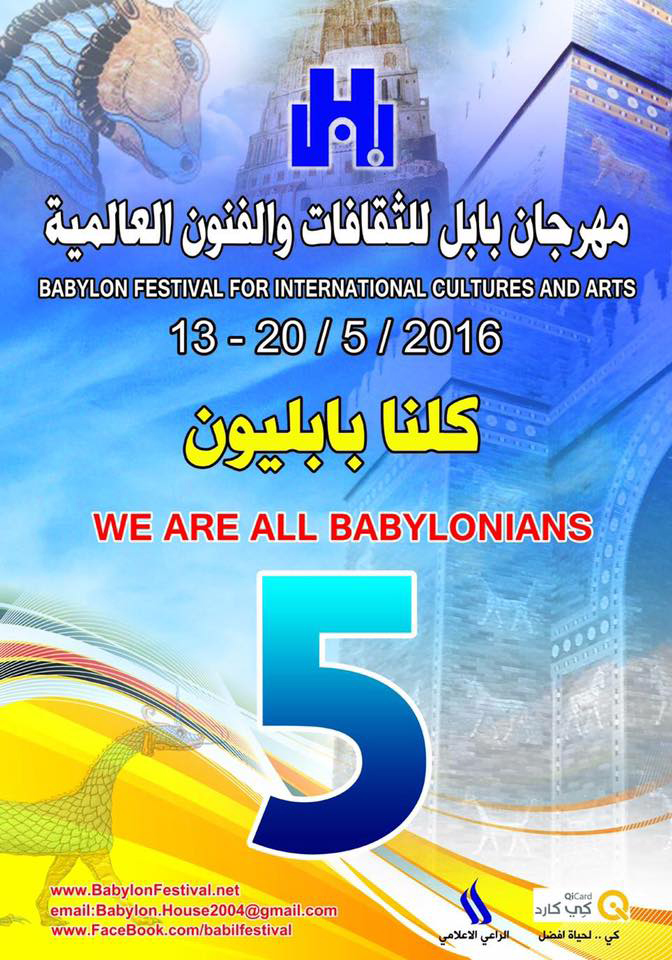

It was the fifth Babylon Festival. The poster displayed a large 5, and also a punchy phrase that seemed doubly resonant after the attacks: WE ARE ALL BABYLONIANS. The message is that we have all descended from ‘the cradle of civilisation’ where writing was invented. Classics of Babylonian literature include Gilgamesh by Sin-leqi-unnini and the Temple poems of Enheduanna, the world’s first ever ‘name author’, a woman. This poetry is as good as anything and should be as known as Homer and Sappho. The city of Hillah is 50 miles south of the Iraqi capital – in the Babylon Province – and just a few minutes by car from the ruins of ancient Babylon. The area had been car-bombed in early March, killing dozens. That had resulted in the festival being put forward from April to May.

.

It was Stop the War Coalition who asked me about availability. Heathcote Williams declined but suggested me. This only added to the culture vs barbarism theme. Iraq is still a war-zone and UK and US airstrikes still ongoing. I was glad enough to be travelling with an Irish passport. War would prove to be one of the major themes of the Iraqi poets and artists featured. Ironically, a precursor Babylon Festival had been inaugurated by Saddam Hussein following the first Gulf War. Saddams’ ghost is everywhere in Iraq, casting a megalomaniac shadow.

.

The 5-hour flight to Baghdad in the company of the English poet Agnes Meadows was effortless. Founder of the original forum for women poets, LOOSE MUSE, Agnes was a regular visitor to the Babylon Festival and able to answer questions en route. Suddenly the in-flight intercom was asking us to prepare for descent. I was blown away by catching a first glimpse of the Euphrates from my window seat. Our photocopied ‘I.O.U’ visas did not get us through customs, but we were allowed to fetch our bags from the carousel. Then we waited, the first of many waits.

.

.

2

.

Unexpectedly, the car took us through Baghdad. As the airport is southwest of the capital we presumed we would avoid it, but our driver was also picking up other attendees. We were suddenly in a huge urban space. ‘What city is this?’ I asked. ‘Baghdad’ said the driver nonplussed. He gestured to a wall. ‘There… the Green Zone.’ The first impression was of vastness, the second an onslaught of sun. Who was the hipster of the many bearded statues? It was Hammurabi, the giver of laws to the Iraqi people. Moses was a copycat.

.

After the city was a highway through the flatlands of the fertile crescent. The infrastructure was poorly, smashed by bombardment to something between building site and ruins. In the middle of the busy intersection was a woman in a wheelchair with a terrifying look on her face, and hands outstretched. Drivers would stop to offer her dinar notes. (The Iraqi dinar is like the Italian lire used to be). Much palm trees and rubble. There were regular checkpoints. Our ministerial visas meant we got through without interminable queueing. I dozed off slightly and awoke to see an amazing multicoloured row of parked lorries.

.

Soon we pulled up at a stately enough building seemingly in the middle of nowhere. It was a hotel designed by Saddam, informed Agnes. The Arab sign apparently says ‘The Old Babylon Hotel’. Inside the furniture was grotesquely gaudy, the chandeliers outlandishly outsized. Framed shotguns hung on ether side of an impressive conference table, regularly hired by grandees. The rooms were spacious and stylish. It felt weird to be accepting the posthumous hospitality of a deposed tyrant. But good. The last thing he would have wanted was an entourage of poets.

.

.

.

Behind the hotel was something more astonishing, the Euphrates. In theory, visiting artists were not supposed to wander off by themselves. Discreetly armed escorts were at hand. But the river was near, just at the hotel’s rear. Saddam had commissioned a terrace on its banks for power breakfasting. Today was Friday, the Islamic day off. Families were picnicking on the grasses, enjoying nature, the power of water. Babylon, like most of Iraq, is landlocked. Despite its somewhat littered, polluted state, it was a gorgeous full-flowing turquoise river. I would like to have swum it but desisted. There were too many reasons not to.

.

.

.

.

3

.

Saddam’s Summer Palace is built on an artificial hill. Another deserted hill a few miles away was also created as a contender, but its view of Babylon was unsatisying. A golden marble monolith, hacked for relics, graffitied, and with a basketball hoop adding insult to injury, it is a spooky ruin. Though unpleasant to visit, I was reminded of Robert Montgomery’s hopeful aphorism, ‘All palaces are temporary palaces.’ Here was a serious piece of evidence. This palace of fear had fallen. One side overlooked the river, but when I crossed through the shell to check the view from the other side, I was astounded again. It was Babylon, a mix of Saddam’s film-set reconstruction, and the genuine rubble of the ancient capital. I hadn’t realised that we were staying right in the heart of Babylon.

.

Looking downhill to the deserted, fenced-off site, on the public day-off, I realised that here was a unique opportunity for an unforgettable walk. I descended the hill to a road and continued on to a smaller rougher track with disused public conveniences. From the track there were tantalising vistas. The ancient capital was still extant and I was an enemy intruder spying out its dimensions. A plastic blue dustbin only added to the sense of time-travelling. .

.

A way into ‘the zone’ became apparent. I stepped over a thick carpet of dessicated palm fronds, walked up a mound of baked mud, and soon found myself facing a wire fence, looking through it to behold the truth of David Gascoyne’s line ‘Babylon the Great is now but dust’. Worried about arrest for trespass, I thought of turning back but found my feet were already pacing towards what was a clear breach in the security cordon. Someone had snipped the barbed wires. I shuffled in. My mock-leopard shoes were already coated in the dust of Babylon. It was slopes, sands, stones, foliage. White cotton was a sparse but insistent offering. I knew that certain mounds were the remnants of prominent places in the city, Marduk’s temple, Nebuchadnezzar’s palace, even the Tower of Babel.

.

Three figures in beautiful traditional garments were walking my way. They were not guards but fashionable youths enjoying their day off. One said ‘Salaam’ and shook my hand. Another said ‘Babylon’ and smiled. Another asked if he could take a photo of me with his friends and we posed. They wended on, examining the charged terrain. To my left I saw another figure, unmoving, made of black basalt. It was the Lion of Babylon, a powerful but now faceless animal standing over a helpless man, perhaps symbolising what would happen to enemies who attacked the city. This was where Belshazzar had seen the writing on the wall shortly before his assassination, and where Alexander the Great had died prematurely in Nebuchadnezzar’s palace. The atmosphere was Ozymandian. Saddam, the man who would be Nebuchadnezzar, had fucked it up with his tacky unfinished reconstruction. The U.S. military had fucked it up by turning the site into Camp Alpha. Vilified in the Old and New Testaments, Babylon never stood a chance. Now it’s a theme park waiting to happen. Only one obstacle remains : Daesh.

,

.

4

,

At the opening night I sat in the magnificent Ancient Babil Theatre with the co-founders of the festival, the German poet Tobias Burghardt and the Argentian poet Jona Burghardt, his wife. The goodwill that characterised the festival and made it run so smoothly emanated from them naturally. Kind and intelligent in equal measure their laid-back attitude made it easy for everyone to cope with any delays, uncertainties or culture-shock. The other mover and shaker for Babylon Festival is the dynamic Dr. Ali Al-Shalah, always on the phone arranging peoples’ safety. The ceremony was invigorating.. Poetry, music, theatre. An actor delivered a monologue on the huge stage festooned with war-zone props. He was telling of life as a soldier in the Kuwait War, the Gulf Wars, and the war against Daesh. Though a one-man show, the denouement was made more theatrical with the invasion of the stage by performers dressed in black masks and robes.

.

.

Another performer epitomised the spirit of the festival. It was the cellist Karim Wasfi, famed for playing his instrument at bomb-sites and Principal Conductor of the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra. He is one of Iraq’s foremost public figures, an artist-activist in the mould of Daniel Barenboim. He is a peace campaigner and secularist who deplores the sectarian nature of the current atrocities but regards them as a distraction from the more important issue of corrupt and incompetent government. He performed a superb original composition called ‘Live’ (as in ‘live music’) which experimentally fuses the Iraqi national anthem with more atonal improvised musicianship. A leonine man in a white robe, his outspoken views and street performances make him an obvious target for terrorists, but he willingly risks his life on a daily basis for the sake of free artistic and political expression. His anti-government views were even more strident at this festival because this was the year the Iraq authorities have cut all arts funding, claiming they need to divert the resources to the military. This itself is a victory for barbarism. All of us poets and artists attending the festival were doing so in support of Karim Wasfi’s example.

.

.

,

The week was well organised and, within Iraq, well publicised. Everyday a pullout featuring poetry, photographs and festival news was included in the daily newspaper Al Sabaah. One regret is that though I heard many great Arabic poets, I was not able to understand their poetry, I could only follow the music of their voices. One poet, Muwafak Mohammed, was particularly impassioned. Tobias told me that he had gone underground in the time of Saddam, disguising himself as a tea-seller and running his own stall. Saddam had avenged himself by killing Muwafak’s son.

.

.

Visits to the souk, the Hillah Contemporary Museum, various art galleries and theatres were accompanied by security. At the souk an impressive man in keffiyah and robes approached me and said; ‘Tell your friends in the west that the Iraq government has killed Iraq! Good day.’ He disappeared then reappeared. ‘Tell your friends the Iraq government is not protecting the Iraq people, it only protects itself! Good day.’ He managed to be both very angry and very friendly. The Iraqis we met were amazingly courteous and welcoming. Despite the games of the military-industrial brokers, Middle-East and West, humanity survives. Another image haunts the townscape from lampposts and buildings, that of a handsome young bearded figure, an icon reminiscent of Christ or Che. It is Hussein, grandson of the Prophet Mohammed, and an early Shia martyr. It is not just the Iraqi Army that fights Daesh, a voluntary Shia militia also braves the Western deserts and northern conurbations to defend its people from Sunni terrorism. We met one man with his arm in a metal brace; he had been hit by an RPG whilst driving supplies to Shia fighters. Most people are pacifist, wishing war to end, trying to build their lives in stability. The efforts of the arts community help the rest of the community. The poets voice mass hopes and despairs, sometimes to mass audiences. Non-violence is the message and the will of the majority. The reason we stand for culture against barbarism is that we are graduates of the Mesopotamian cradle, WE ARE ALL BABYLONIANS.

.

Text: Niall McDevitt

Photos: Babylon Festval

.