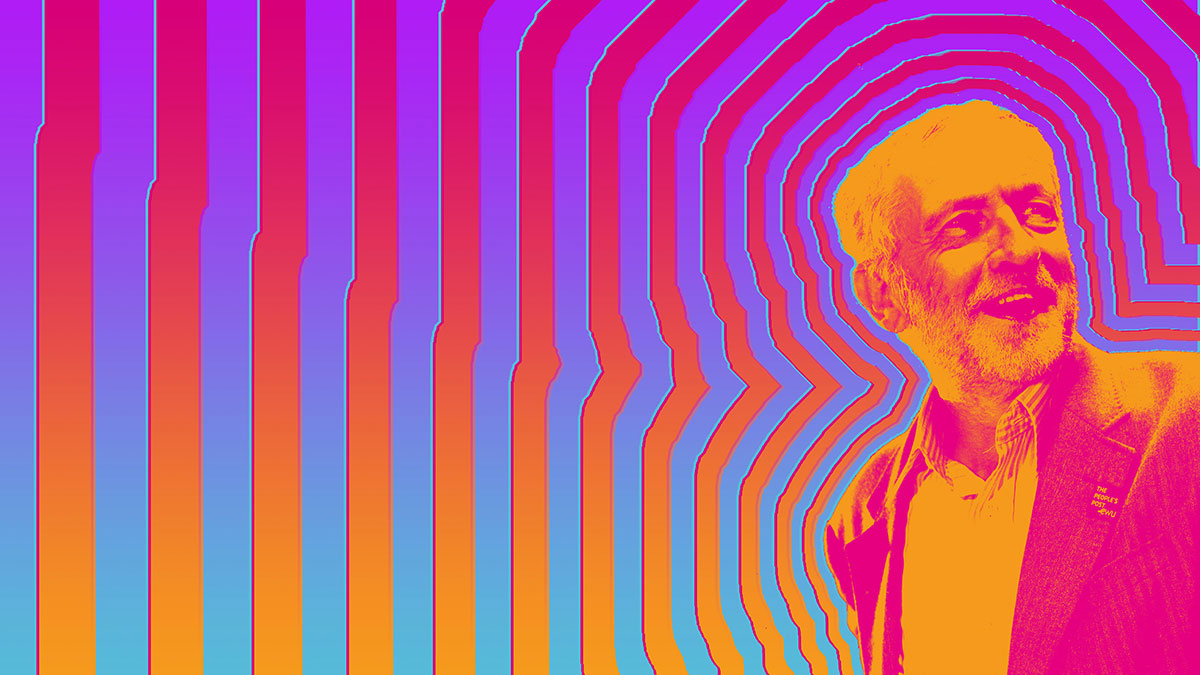

Jeremy Gilbert on how radical Labour politics can be inspired by the utopianism of the counterculture

Illustration: Tom Lynton

Illustration: Tom LyntonBefore my friend Mark Fisher died in January, he had been working on a book called Acid Communism. This was Mark’s term for a utopian sensibility shared by the political radicals and psychedelic experimentalists of the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s. It rejected both the conformism and authoritarianism that characterised much of post-war society and the crass individualism of consumer culture. It sought to raise the consciousness of individuals and society as a whole, be that through the creative use of psychedelic chemicals, aesthetic experiments in music and other arts, new kinds of household arrangements, radical forms of therapy, social and political revolution, or all of the above.

Mark had no personal interest in psychedelics. He liked the idea of ‘acid’ as an adjective, describing an attitude of improvisatory creativity and belief in the possibility of seeing the world differently in order to improve it.

In fact, when we first got to know each other, he still considered himself a hippy-hating post-punk, utterly dismissive of the legacy of both the summer of love and the radicalism of ‘1968’. But I (and others) persuaded him that it was a mistake to go along with the views of figures like Slavoj Zizek, or Adam Curtis, who simply dismissed the counterculture and the radicalism of the 1960s and 70s.

These commentators tend to focus on how the utopianism of the counterculture apparently led directly to the banal individualism of ‘new age’ and late 20th-century narcissistic consumerism. I have always argued that those outcomes must be seen as distortions of the radical potential of the counterculture, which had had to be neutralised and captured by a capitalist culture that found itself under genuine threat from radical forces in the early 1970s.

Technologies of the self

From this perspective, techniques of self-transformation like yoga, meditation or even psychedelic drugs, in theory, might have some kind of radical potential if they are connected to a wider culture of questioning capitalist culture and organising politically against it. By the same token, they can easily become banal distractions, ways of enabling individuals to tolerate every-intensifying levels of exploitation and alienation.

These ‘technologies of the self’, to use Michel Foucault’s term, have no inherent political meaning. From a progressive political perspective the question is whether, and if so how, they can be used to challenge entrenched assumptions of capitalist culture, enabling people to overcome their individualism in order to create potent and creative collectivities.

For the women’s movement of the early 1970s, the most important ‘technology of the self’ was probably the ‘consciousness-raising group’ – small groups of women who would meet to discuss all kinds of personal and social issues from a feminist perspective, seeking to liberate themselves from sexist and patriarchal assumptions. This was also the moment when black power and the gay liberation movement reached their most intense levels of politicisation, and when the politics of the ‘New Left’ was at its most influential.

What linked together all of their political positions was a rejection both of traditional hierarchies and of any simple individualism. These movements were libertarian, promoting an ideal of freedom, but they understood freedom as something that could only be achieved or experienced collectively.

Higher consciousness

Mark was interested in reviving the idea of ‘consciousness-raising’, and in theorising the effects of capitalist ideology in terms of ‘depletion of consciousness’. This is a way of thinking about the techniques used by various apparatuses of power – from school league tables to the tabloid press.

As many previous writers have noted, such institutions operate not just by feeding us false information, but also by affecting us emotionally in order to make us feel less able to act in the world, less able to think creatively or dynamically. From this perspective, ‘raising’ consciousness isn’t just a matter of giving people information about the sources of their oppression. It is also about enabling them to feel connected and alive, personally and collectively powerful enough to challenge their oppression.

There’s a fascinating confluence between the idea of ‘higher’ consciousness that emerges in some of the mystical, yogic and philosophical literature of the 20th century and the idea of politically ‘raised’ consciousness that became so central to 1970s radicalism. Both of these ideas had older antecedents.

Radical politics can take strength and inspiration from cultural forms that promote feelings of collective joyThe idea of raised political consciousness had its roots in the Marxist idea of ‘class consciousness’, whereby workers come to realise that their shared interests as workers are more significant than their private interest as individuals, or the cultural differences they may have with other workers. The mystical idea of ‘higher’ consciousness has its roots in Hindu and Buddhist ideas of the individual self as an illusion. Escape from that illusion, realisation that the self is only an incidental element of a wider cosmos, is sometimes referred to as ‘enlightentment’. But the original sanskrit and pali terms might be better translated as ‘awoken’. Maybe it’s not an accident that ‘woke’ has become a popular radical slang term for raised political consciousness.

Collective joy

Many writers thinking along similar lines have argued that radical politics can take strength and inspiration from cultural forms that promote feelings of collective joy (festivals, disco, etc), overcoming the alienating individualism of capitalist culture. An interest in this, and all of these other ideas about consciousness-raising and radical social organisation, motivated some of the organisers of The World Transformed, and Labour activist Matthew Phull, to approach me about the possibility of creating a space to discuss them at this year’s event.

It was Matt who came up with the phrase ‘Acid Corbynism’, a suggestive term implicitly raising the question of whether it would be possible to link the politics of the current Labour left to this tradition of utopian experimentalism.

In fact, there are already historical links between them. A crucial feature of the politics of the New Left was its critique of bureaucratic authoritarianism, in the public sector and the commercial world. The radicals of the New Left called for the democratisation of households, workplaces and public institutions, from schools to the BBC.

Labour’s general election manifesto made few concessions to this tradition, being almost entirely a list of things that central government would do and rules it would impose. But last year Labour commissioned a study into the feasibility of implementing new co-operative and radically democratic forms of ownership of enterprises and services, reminding us that the call for workers’ control of industry was part of the radical tradition associated with Tony Benn and his followers in the 1970s and 80s (the most famous of those followers being Corbyn himself).

Although critics of Corbynism see it as a personality cult focused entirely on the leader himself, Corbynite activists have found themselves part of a largely self-organised movement, seeking to raise public consciousness and their own political effectiveness through the use of cutting-edge communications technologies. Perhaps campaigning apps and organising platforms are our new technologies of the self.

Whether these radical tendencies can be developed into a full-blown project to democratise British institutions (including the Labour Party) remains to be seen. But history suggests that political and social change on the scale we seek must be accompanied by extensive cultural innovation. Pro-Corbyn memes and football chants are a start. What new forms of expression may emerge in the years ahead, nobody can predict. It seems certain, however, that the struggle against neoliberalism and authoritarian conservatism will still require forms of culture that are collectivist without being conformist, liberating without simply breaking social ties.

The World Transformed session on Acid Corbynism is from 9.15pm on 25 September at Fabrica, Brighton. Session info and the full programme. A longer version of this piece will appear on Jeremy Gilbert’s blog next week.

Why not try our new pay as you feel subscription? You decide how much to pay.

There was something essentially ecstatic and joyful about the 60’s but it was underpinned by determination and a certain amount of discipline inherited from the 50’s. I don’t see that quality in Corbynism which is flabbily self-righteous and leaden footed. The world might be ready for another Che Guevara to throw himself – or herself – into the breach, somebody with the combination of low cunning and high morals to be an effective revolutionary. What it doesn’t need is another jam making geography teacher spouting platitudes from the 70’s.

Comment by DJC on 3 October, 2017 at 9:29 am