Before the days of the ceramic garden gnome, a human being often played the role of stern, robe-wearing guardian of flora and fauna — and that person was preferably a grizzled old man who didn’t mind living in seclusion and forgoing even basic personal hygiene.

Meet the ornamental hermit.

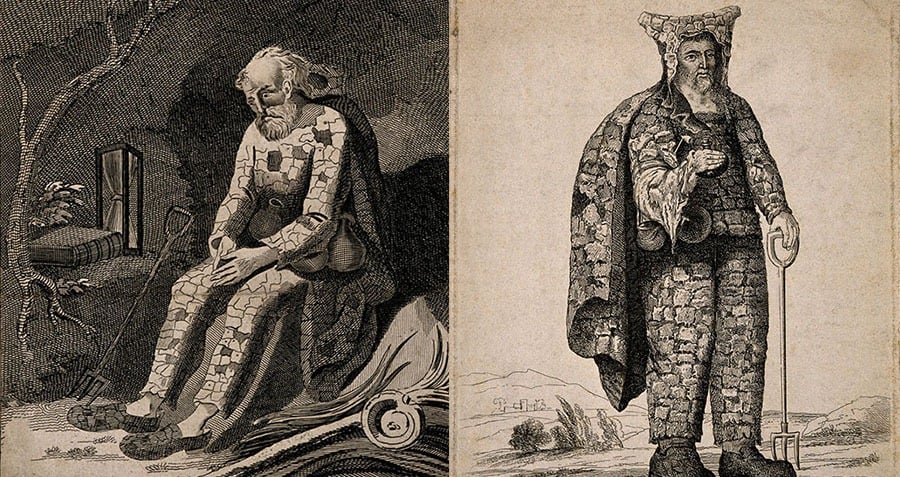

Wikimedia Commons

Two trends in Georgian England created a moment in history for the phenomenon of ornamental hermitage: solitude and overt displays of material wealth.

Wealthy landowners desired expansive and often ornate gardens on their property, and would use these expanses to reflect not just financial riches, but existing social mores such as melancholy.

Elite circles viewed this deeper, more introspective form of sadness as a mark of intelligence, and thus sought to associate themselves with the sentiment whenever possible. Physical property presented an easy, obvious avenue to bring this social virtue of melancholy to life.

Soon enough, wealthy landowners began placing want ads in newspapers to fill this very aim. Ad writers often sought men who would agree to live in a garden for a span of time (usually about seven years, it seems) and devote themselves to a silent, forlorn — if not also wise and mysterious — existence. One such ad placed by Charles Hamilton outlined the expectations for a hermit-in-residence as follows:

…he shall be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a hassock for his pillow, an hourglass for timepiece, water for his beverage, and food from the house. He must wear a camlet robe, and never, under any circumstances, must he cut his hair, beard, or nails, stray beyond the limits of Mr. Hamilton’s grounds, or exchange one word with the servant.

The more eccentricities the hermit possessed, the better. While some consider modern day hermits’ preference for sequestration pathological, 18th century Europe lauded an individual’s proclivity toward solitude, and paid a pretty penny to those willing to go nearly a decade without a bath or new clothing.

This was a tall order, and some men who took on the position couldn’t stand the life for more than a few months or years. These men must have been rather miserable, as hermitage contracts often stated that if the hermit left before his tenure ended, he would also forego payment for his services.

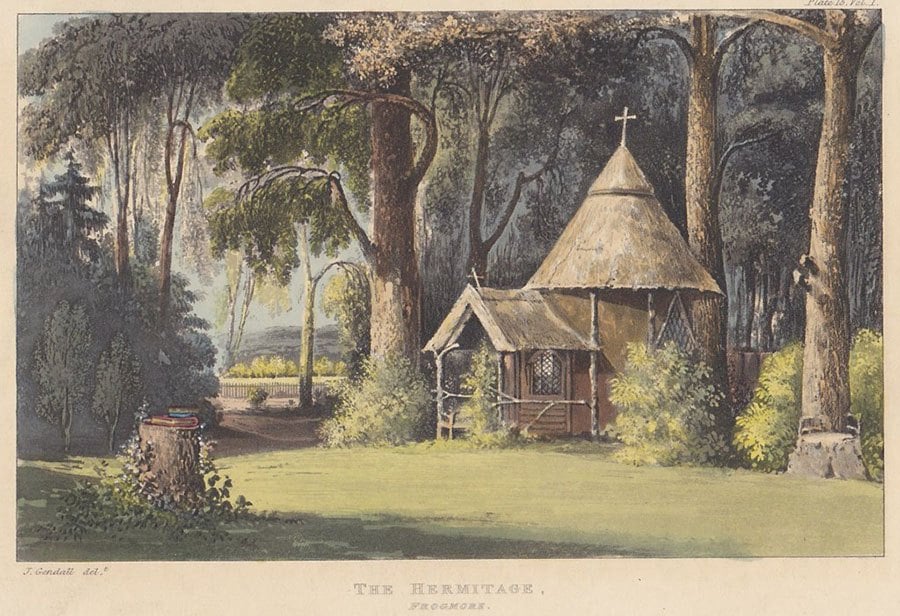

Public Domain

For those who stayed, life was fairly straight-forward. Most hermits lived in small shacks or caves built for them on the property, and offered themselves to guests as a silent, physical symbol of solitude and the nearness of death.

Not interacting with guests was the hermit’s key job function — at least most of the time: some accounts tell of hermits performing duties such as light agricultural work or bartending garden parties.

More often than not, though, the hermit’s existence justified his paycheck. Not unlike the way a nobleman of the era would have shown off his prized mare or his lovely wife, an ornamental garden hermit provided the elite another asset for others to praise.

For those who couldn’t afford to actually employ a hermit, they often set up a hermitage to imply that a hermit may soon arrive or had just departed, which offered the property owner a similar air of prestige.

As cultural and technological changes shifts led society away from the maudlin and excessive — and treating humans as ornaments — the garden hermit soon swapped skin and solemnity for glass and kitsch to become the ceramic garden gnome we know today.

As with all obscure practices from days yore, if you dig around the internet for long enough you can usually find someone eager to usher in its revival: In the summer of 2014, an advertisement appeared on Craigslist: Gentle Lady Seeks Ornamental Hermit.

While the not bathing or speaking for several years may be unpalatable for many, as far as job duties go, “Reminding all passersby of our shared mortality” certainly beats data entry.