Dead, the conscience is dead, and knowing lost to knowledge. Closed by a magnetism acting on the blood’s iron, drawing the front of the brain cold, all those skulls that have grinned . . .

A sunrise has potential; sunset is the end.[i]

The first real escape many children have is by bicycle. Even if it is only to loop alleyways and garages, marked by lampposts and the occasional privet hedge of a class ascension internally clasped within net curtains. Breaking these fenced orbits among flats and terraces, some went further. On bikes hardly fit for the purpose, five miles out into overhanging summer, was as good as a voyage to the source, at least at the age of 7. The cow-parsley that lined the lanes was a miracle; the pub signs advanced from Eden. No doubt such escapes were exaggerated for my generation by the comparative freedom of the 60s and 70s. At weekends and especially on Sundays my mum and dad weren’t concerned what I was up to. They could ignore the neighbour’s dog barking as I crept away. They looked forward to a lie in. Boys particularly were expected to be outside and disappear. Apart from the assurance that I had a tuppeny piece for the callbox (two new pence we were supposed to say), my mum cast no restrictions; while the claustrophobia of helmets, the stupid prescription of sportswear and lycra, hadn’t been invented. In the event I never used that emergency 2p. Alone or in company, we always had a few rusty tools and a pump. Our bikes were too simple to go seriously wrong. They rarely had gears. Brake repairs could be improvised. Punctures were common but easy to fix. Who was I supposed to phone anyway? They had no phone until I was 14.

The dawn scene[ii] which opens Donnie Darko (2001)[iii] – filmed somewhere off the Angeles Crest Highway[iv]– has a grandeur which the view from high beechwoods[v] and rough grass hills looking over the Vale of Aylesbury, at least through my eyes of 1973, could perfectly match. This subconscious identification before even 60 seconds of Donnie Darko’s screening on 19th of March 2003 at the Taunton Odeon[vi], drew me in entirely.

As thunder left over from the pitch night of credits, gives way to faint birdsong, the viewer’s consciousness drifts towards the figure in the road. An ominous ambient drone[vii] is displaced by gently melancholic piano and ethereal vocals. Donnie awakes by his recumbent bicycle, to pass through several fleeting changes of mood ending with a short laugh. A whiteout cuts to Echo & The Bunnymen’s Killing Moon[viii]. Rubbing his eyes and frequently in the wrong gear, Donnie begins his lackadaisical cycle home. A rising sun flickers and flashes through woods; the blue of the sky gains confidence. This downhill journey recaptured the atmosphere of the Chilterns again, for the elevated road on which Donnie coasts homeward, recalled a new lane laid out in the early 70s, above the Hale valley and over the ridge – a silent route I first discovered alone, very early one morning, seven summer miles out. From its high end by the endless view from the escarpment, no clear effort was required to whirr, falling and rising through the beechwoods, strobing past the trunks as if in flight. With only a few turns of the pedal cranks, each crest renewed the previous altitude – to give the impression, as the dawn air and all the smells and sounds swept past, of swooping downhill for leagues. Although this new thread of tar between shining leaves and fresh-cut chalk and flint cuttings, can’t have been more than a mile or two in length – and judging by maps has picked up a lot of traffic and destinations in the decades since – it flowed naturally into the descent of the Hale valley. Dropping onward through the Wendover[ix] gap, it was possible, within two or three miles of the escarpment summit, to virtually freewheel into English versions of Donnie’s wealthy suburb – though nothing in Wendover was as widely spaced or lavish as Country Club Drive, Long Beach, California, appears in the film[x]. Due to the capacity of films to contract and expand time and space, editing distant locations together, Donnie’s bike ride of less than 90 seconds, in ‘real life’ would involve a distance of 70 miles! Such brevity interestingly encapsulates the superiority of the best films over long-form TV[xi]. Relentlessly, one could expand the characters and milieu of Donnie Darko to fill several series. Yet despite all the extra verisimilitude and incident, essentially, you’d get no closer to the people or places. Meanwhile the film’s mythic nature, its universality, would inevitably be diminished[xii]. Such a series might be popular, a money-spinner, a cult favourite – none of which would stop it being a waste of valuable leisure time. Is this the Big Brotherish, inadvertent, or secret Neo-liberal aim of long form TV? To be the ultimate opium of the people? Encouraged by a growing global obsession with trash and gossip, how many can resist being tempted by such time-wasting[xiii].

Inwards is outwards there can be no fear.[xiv]

If I happened to mention that I was going out next day, my mum would encouragingly make a sandwich and drink to take, then give me a 2p from her purse. But from about age seven, often I’d go spontaneously, just leaving a note on the table: “Back by dark.” My sister wasn’t so lucky, generally parents worried more about daughters. But of the kids on our council estate, most boys and a few girls had a freedom similar to mine – albeit commonly arising from neglect. Only a few, perhaps those with the most aspirational parents, were confined to their garden or street. Curiously, even given liberty to roam, many were content with the estate – its hidden areas, alleyways and small bits of green. At the time it seemed a couple of miles across. Others went up town.

K and I tried to give our children a similar freedom from the late 1990s. This was only possible to consider because we lived in a quiet inland part of North Devon. Where I grew up was not so remote: 42.9 miles from Waterloo Bridge – or so a modern device suggests as the best cycling route. Yet at the time, parts of Bucks could feel sylvan and detached. Perhaps some still do? To the north and east of an estate largely constructed to house “London overspill”, the landscape was rural, undeveloped and mostly deserted. Even back towards the wealthy commuter belt, up on the Chiltern Escarpment, at dawn it could seem like the very first world: a paradise beyond the grasp of suburbia . . .

Like a goat with a mouthful of questionable lingerie – cake-like but mystifying, a surface covering something ineffable – the universality of inevitable nostalgia, is something I can’t help chewing on, cannot bypass. Most things I feel driven to write either stem from it or circle its Corryvreckan-like force[xv].

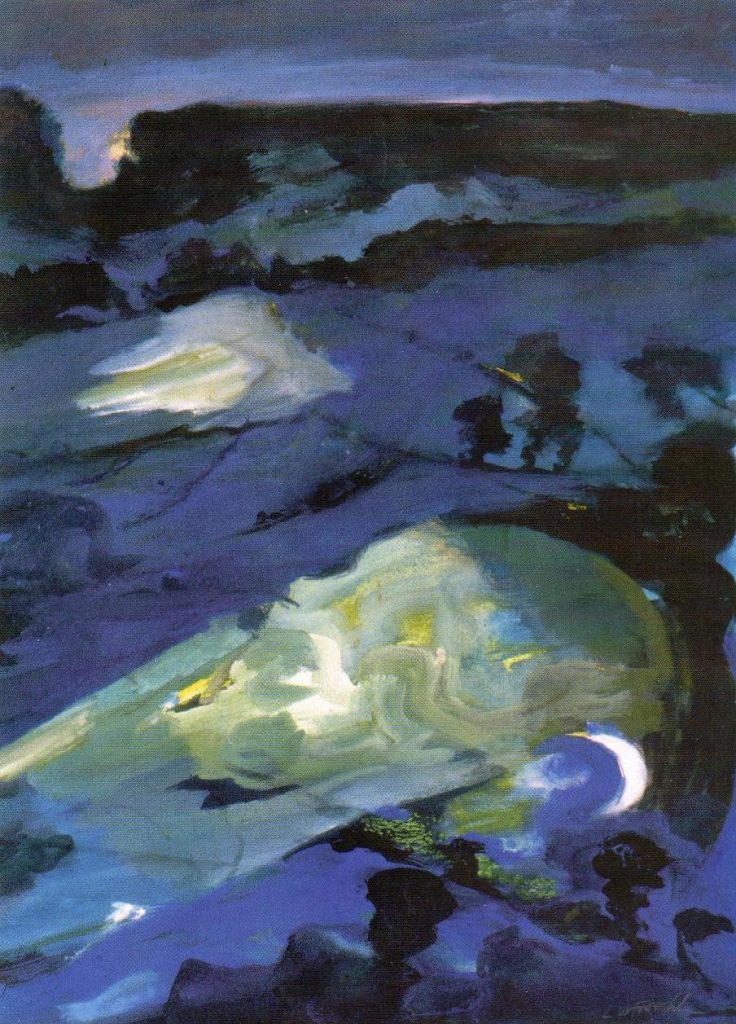

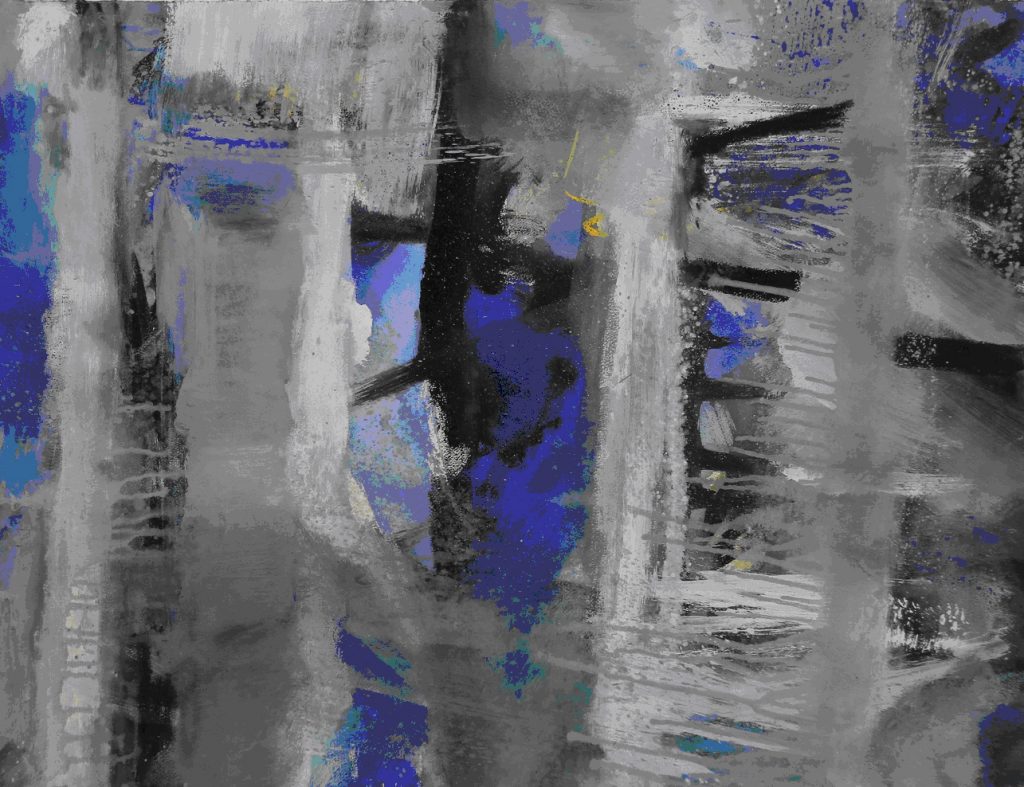

Only the best paintings somehow eclipse this inescapable obsession. The often-repeated journey towards their vertiginous tranquility, kept me partially sheltered in hope for thirty years. The smell of paint, the transitory borderlands of colour and shape, usually dissolving to nothing, but occasionally reaching a place I could never have foreseen . . . I lived in the potential of their balm – for many periods barely noticing time or space, aging or location.

With the exception of its poetic extremes or outriders, writing is necessarily more rationalistic, more tied – forcing those using its path to attempt analysis of what in the end will always be beyond it.

“Reality is pinched and parsimonious. Its project has failed . . .”[xvi] The rafts of feeling which spiral up uncontrollably every time I digress from reality[xvii] return with regularity – atmospheres filled with a hope that can never be fully grasped: the secret in the hills; the unknown person under the roof . . .

Re-watching the shorter theatrical cut of Donnie Darko – a clear case of “less is more” – with two of my children recently, many of these strong but untraceable feelings where stirred again. The world that will end in “28 days, six hours, 42 minutes and 12 seconds”, is eminently recognisable. Perhaps due to the “colonization of our subconscious”[xviii] such American neighbourhoods seem easily transferable, their attitudes, universal – at least to similar western societies. The cult expansion of Donnie Darko, for all its frequent daftness, is perhaps a more ideal form of hyperdiegesis[xix] than most? This expansion is something I’ve largely ignored, preferring not to sully the film’s archetypal universality with abstruse theories. Its 80s particulars are not of my generation. Apart from as an inducement to parents to spend X amount of petrol in certain garages[xx], I knew nothing of Smurfs, and wasn’t familiar with the songs made yet more iconic by the film’s soundtrack. Do the Pet Shop Boys (or their management) regret missing the extra glory they might have gained, had they wanted less money for the rights to West End Girls?[xxi]

Although I was 10 years too old for Donnie Darko’s milieu[xxii], grew up on the other side of the Atlantic and the other side of the tracks to the wealthy characters depicted, as with Alison Anders’ Things Behind the Sun[xxiii], Richard Kelly’s film mainlines into a universal well – flooding out as surely as Donnie’s axe in the Middlesex High School basement, our particular schools and homes in favour of an archetype.

But wait a minute, there’s a crucial personal factor I’ve overlooked: I was lucky in my life to be able to turn back the clock – in a sense, to repeat those vital teenage years. Unlike the first time, I was very self-consciously aware of my second chance – intensely in and yet partly above the days.

Employed part-time as a youth worker in the exact period in which Donnie Darko, is set[xxiv], I inevitably mixed with young people the age of its characters. Although this was a town in the West Country, a fair proportion of those who came to the youth club lived on deprived estates. Yet the landscape was beautiful and 1988, 1989 and 1990 blessed with long periods of rich summer light. High hill ridges encircled the settlement, over which to the south, the sea under red cliffs, wasn’t far away. There were even small pockets of suburbs almost as wealthy as those depicted in Donnie Darko – suburbs through which we could cycle, and golf courses where we would be disapproved of. At twenty-six I wasn’t so old that it was impossible to go back, to relive that opening of potential again, alongside those still closer to it. It was there that I met K – she was my Gretchen Ross[xxv]. Honiton in 1988, became to me what Wendover had been eleven years earlier. And Van Morrison’s, Beside You[xxvi], became our joint anthem.

Donnie Darko, the film itself, exemplifies both the self-doubt and the sometimes recklessly hubristic ambition of youth, as well as its desire for unhypocritical truth – a desire which the best of us never lose. Despite deploying such arrested concepts as literal time travel, the film accurately satirizes the crazy self-deception of the everyday world, while keeping both earthly beauty and the sublime within its compass – all of which is amplified by Donnie’s precarious enlightenment and grounded by his anguish.

Naturally certain aspects of Donnie Darko are hard to take – things which if one had kept a diary at his age, would quickly become embarrassing. Fortunately – with Jake Gyllenhaal as his ideal stand-in or alter ego – the adult Richard Kelly is too sincere, too honest to suppress his past enthusiasms. Freely referencing all the films he must have loved, Donnie Darko goes much further. It is far better than E.T., (1982) or Back to the Future, (1985-90). It is more of an outsider, it goes deeper; and yet for all its fantasy elements, it is also more down to earth, more fundamental – internal yet universal. It underlines that all the best art is already inside you.

I don’t care about theories of literal time travel. We can time travel in our mind any time we want. My living memories of Honiton are time travel. Literal time travel, by contrast, is ludicrous – far less believable than say the existence of gods. It’s controverted immediately (or maybe not, I don’t care) by the fact that no-one from the future has ever come back to tell us about it . . . unless that proves we have no future? In fantasies and speculations, time travel as a metaphor or as a confusion in the brain, can be thought-provoking, enjoyable or tragic. But in the end, all the stuff about wormholes, portals, liquid spears and jet engines, looked at too literally, is just silly – and so it’s surprising how well the fantasy aspects of Donnie Darko work. Even the CGI cloud-gathering vortex, successfully suggests the cosmic.

A quality in memory makes it different from mere recording. It has an element that goes against its apparent implication of time.[xxvii]

While I would disparage the over-explanatory Director’s Cut – which Kelly himself suggests in 2016’s Deus Ex Machina: The Philosophy of Donnie Darko, was premature and indulgent – many of its additional scenes do add something, and although once seen, they can be retained in the mind without disrupting the flow of the concise original, at times I’ve missed their living, breathing, presence. There’s a parallel here with the way friends often remember shared events quite differently. Or with the strange doubt we sometimes have over whether certain crucial moments in our life history ever actually occurred at all[xxviii].

One of composer Michael Andrews’ themes[xxix] for Donnie Darko has for me a strong associative overlap with the poignant music[xxx] used at many points in Granada’s 1979-80 TV adaptation of Catherine Cookson’s The Mallens[xxxi]. Re-watching the scene[xxxii] after nearly 30 years, where in a jealous rage Juliet Stevenson strikes a farm girl with her riding crop, I was reminded of the delicate tragedy of this music, despite the melodrama that develops on screen: poor struck girl rolling down steep Allendale hillside ends up ravaged by a random plough. Would impoverished 19th century farmers have left such valuable machinery lying around in fields? In the next shot it seems as if the plough has jumped up and run over its victim several times. In a rush, another farmworker struggles up the hillside, hurrying to fetch the doctor. He claims he can reach Allendale faster on foot than on horseback – perfectly plausible to anyone familiar with the terrain – yet takes time out to call Juliet Stevenson a “murdering bitch” and beat her with what sounds like a duff coconut or hollow rock. Astonishingly, when she recovers consciousness some scenes later, this attack (arguably more brutal than her hot-tempered single strike), cures her long-term deafness. Amazing! Happy day! Every coconut has a silver lining! Yet in Random Harvest (1942), Ronald Colman, loses and later regains his memory in equally implausible fashion.

Like Donnie Darko, Random Harvest plays with time. And the intensity of its end, if you can fully enter into its devastating 40s wistfulness, disregarding its absurdities[xxxiii], depends partly on the sense of wasted time[xxxiv]; on the deeper connection the two main characters might have had, living in their studio cottage by its studio stream with the perpetually blossoming cherry tree outside, above the gate whose squeak has become so poignant. Had anyone ever oiled that gate, the painted landscape for miles around would have been diminished. Considering the life they missed, and the child who has come and gone without his father ever knowing he existed . . . is a form of exquisite pain. This is no ordinary romantic end, (“sentimental tosh” according to K), and every time I register its meeting-again-melancholy of time lost and partly recovered, it breaks me in half. Colman’s resigned realisation. The way Greer Garson, says with a catch in her voice, “Oh, Smithy . . .”

Music I become obsessed by, tends to wear out fairly quickly, even if the temptation to overplay it is half resisted. Playing the last few minutes of Random Harvest’s hopeful/hopeless resolution for almost an hour, I wondered if I could break through the cherry blossom to walk the painted winding lanes before I became indifferent.

Nothing needs to be allowed for with Donnie Darko’s bittersweet end, the slow pan over the characters, half-aware of what might have been, and the conclusion in their alternative present aided by the music[xxxv] is so flawless that the only thing it risks is somehow completing itself – an awkward concern of my own as to whether art requires a degree of imperfection to attain true perfection. This may be a question of how closely you look. In certain heightened moods, I can get to the point where every thought that crosses my mind seems a revelation! Such a state of mind is clearly insupportable in daily life. Anyway – to keep to the point – perhaps the idiotic time-travel conundrum provides just the imperfection required to make Donnie Darko perfect?

By contrast, I can’t remember how The Mallen’s ended and can’t really be bothered to find out. Complete with wobbly walls and theatrical overacting, The Mallens often qualifies as trash TV of soapian forgettability, yet there are positives – not least the true grey-greenness of the wonderfully bleak Northumbrian locations. Of course, when the doors of houses shut and the ‘action’ moves indoors, it’s like being shut in a big wardrobe, light years away from the wind and sun outside. But back then TV viewers were used to this cardboard world of up-close thespian angst beneath the flaring of studio bulbs[xxxvi]. Today, viewers under a certain age, may struggle to suspend disbelief. Occasionally though, the acting is powerful enough to blast all production limitations to kingdom come: Take Juliet Stevenson and Gerry Sundquist[xxxvii] in the antagonistic love scene at 58.40[xxxviii] – a scene that like the ending of Random Harvest[xxxix], I also interrogated over and over, as if I could enter its tunnel towards some higher light!

Literal time travel may be an irrelevance, but imaginative or internal time travel is different. Yet although we do it every day, generally it seems to be treated with condescension, nay contempt. By contrast, I often think that so-called reality itself, is only a pale washed-out sketch for the greater truth of memory and imagination[xl] – a conviction which doesn’t synchromesh with my political or environmental viewpoint. Donnie Darko, character and film, struggles in all these crosscurrents – from the personal to the metaphysical. It reminds us that the memory of our inner potential remains valid whether we are young, middle-aged or as old as Grandma Death. It combines the universal with the particular to a paramount degree.

Amongst groupings of inexplicable feelings, the most powerful to me for many years, I entitled The London Feeling (or London Atmosphere). I took this to be a kind of vast nostalgia – universal I hoped, yet perhaps particular only to me?[xli] All kinds of things, predictable or totally unexpected could set this off[xlii]. At an emotive level The London Atmosphere would engulf me in a kind of visionary sensuality, purely joyous, expansive and relaxed, until inevitably, I began to question its origin and meaning. (Alone and shut away, was everyone subject to such racking enigmas, without even one friend who could be bothered to listen, let alone be sympathetic?). Eventually, I assumed The London Atmosphere must be a blurring of my pre-conscious life beneath the age of four at Chiswick and Brentford – ‘from under the flyovers’[xliii] – with the new redbrick world of the Alderhurst Estate, floating on fields at the edge of Arrowsby-on-Lyre[xliv], where my family moved in 1966. There, among all the other exiles, lovers of allotments and retired flower beds, neighbour’s emphatic shouts against washing getting wet: “It’s rainin’!” ice cream vans failing to turn a profit amongst the gardens of car parts . . . there, must have been where this quasi religion came into being?

The Vine Inn as it was in July 2003 – a locus of The London Feeling . . .

Ideal pub gardens have remained key to my own arrested development, my talisman to believe in, and railways also – to out-accelerate, to exceed literal time-travel. All these regressions – everyone should have at least one – are crucial to individual survival. My railway fervour expanded over time into almost all forms of transport – which back then, even if risky, embodied hope rather than destruction.

I’m not sure when it was I finally twigged that all my various atmospheres, those with the ability to reveal and expand a relaxed intensity, had the same universal source – and that this wasn’t nostalgia, but the truth we cannot sustain . . .

Perhaps this revelation was owed to the Vine Inn? 157.2 miles west of Waterloo Bridge down a concealed alleyway in Honiton, sometime around the Millennium, I realized that the environs of The Vine perfectly encapsulated both The London Feeling and also the atmosphere of the Midlands canal-side pub. Beyond the particular was a universal, a time beyond time and a place beyond place.

Hard to believe as it is, these revelations come and go. How often I have to struggle to recover their balm. Occasionally it seems obvious that other griefs of mine, perceptions that cannot be sustained – the purer form of love[xlv], the buried personality[xlvi] and the inevitable lost potential of children – are linked. To take the last grief (that of the child prior to contamination by the wrong-headedness of human society, prior to infestation by the universal technopoly[xlvii]), it often appears at certain moments that the ideal source which informs all “atmospheres” and revelations, is directly perceptible through children – one’s own children or other children, as well as the children we once were. One can only hope that its essence, against the implication of time, lives on in our spirit, regardless of the mass conformism[xlviii] to futile consumer goals, regardless of our inability to grasp and hold onto it.

Art should be a doorway not to the production of more art – too much of which is just a pretty or ugly wall with no openings – but to the more intense[xlix] life around and inside you. Through its atmosphere, its story, its music, and from the potential of some of its children, Donnie Darko summons this intensity.

Despite all my experience before and since, I will always associate the presence of gorse with the Isle of St. Agnes in the Scillies[l], and fried mushrooms (reduced, Lidl, Paignton) with a holiday in a coombe above Teignmouth. If only the driving spirit of occasional revelation, its connective power and possible cure for all griefs, could remain so consistently prevalent.

© Lawrence Freiesleben,

Cumbria, March 2020

NOTES

[i] Paraphrased from the 1982 version of The Bow. [Revised version, Stride Press, 2000]:Bow-Lawrence-Freiesleben/dp/1900152657/ref=sr

[ii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XeZU0km1H0 or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=76IkuYLoJkE

[iii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0246578/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

[iv] California (and the landscape around State Route 2) standing in for the Virginia of writer/director, Richard Kelly’s 80s childhood,

[v] “Further from the lavish beechwoods south of our youth / Far above the individual houses, sequestered in gladed roads” http://internationaltimes.it/hemmed-in-by-the-days/

[vi] First screened in the wake of 9/11, the film died in the U.S. having only recouped 10% of its production costs. Luckily, in 2002, encouraged by word of mouth recommendation, in less than a fortnight it made 50% more in the U.K. than during its entire American run – a success which led to unforeseen distribution in the provinces (including Taunton) and rapid cult status.

[vii] In December 2019, I wrote to Sight & Sound magazine about the over-use of the term Lynchian (see below). In this case however, although it’s fair to say that the opening atmosphere of Donnie Darko, accompanied by the ominous drone, has a Lynchian tone about it – this is soon subverted by one of Michael Andrews’ ethereally bittersweet themes. While other aspects of the film also have Lynchian undertones, as with the many other clear influences, Kelly’s voice is unique enough to transcend them.

LETTER TO Sight & Sound: “I wonder if the lazy use of the term Lynchian (increasing universally, as well as peppering Sight & Sound these days) is due to the youth or suggestibility of the writers rather than to fashion or to an intelligent form of dumbing-down? Obviously, the best works of David Lynch (of which I’m an enthusiastic fan) have a few distinctively ‘Lynchian’ aspects, yet it does appear that many critics have mislaid their knowledge of say, Dennis Potter or Fritz Lang’s, Dr Mabuse – to take just two random precursors. I doubt it’ll help Lynch in the long run, to be gifted credit for half the archetypes long present beside the stranger highways of human culture. Such an annexation of our collective unconsciousness is not only a gross oversimplification but a dangerously misleading convenience – albeit one typical of societal and historical categorisation.”

[viii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LWz0JC7afNQ

[ix] From: http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-6/: A real place under the Chiltern escarpment, but a symbolic place also – one that stands in for many similar towns and villages. The Wendover in my mind, remains how it was between 1970 and 1980, I’ve hardly been there since.

(“but as they connected to other summers, to other rivers, or even to moments that appeared quite dissimilar; to the friend under the roof[xxiv]; to the memory of the exotic[xxv] girls of Wendover[xxvi].”)

[x] http://www.movie-locations.com/movies/d/Donnie-Darko.php An impression gained via that amorphous little yellow google figure, however, suggests that the film emphasises the luxuriousness of the environs by excluding the more average dwellings.

[xi] “As for long-form television and binge watching, I have no desire to become the latest willing sacrifice to such mind-suicide.” From: http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-4/

[xii] You don’t need a TV series to expand upon what the best films latently contain – though the temptations of expansion are inevitable. Recently re-watching the brilliant Klute (1971) I found myself wishing for a sequel. Did John Klute and Bree Daniels live happily ever after in the country? But stories should end. Dragging on forever, they become substitutes for our own lives.

[xiii] Matthew Harle’s review of Birth of the Binge: Serial TV and the End of Leisure by Dennis Broe in the June 2019 issue of Sight & Sound notes that Broe’s “most important criticism” “is that the rise of the serial marks the disappearance of authentic leisure.” “The serial drama has become part of Capitalism’s last hope and stands as a “beacon for its promise of abundance and the site of its last pretensions to equality”. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/41709967-birth-of-the-binge

“When we binge, Broe claims, duration and endurance have replaced pleasure.”

[xiv] From the 1982 version of The Bow.

[xv] The famous Scottish whirlpool. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulf_of_Corryvreckan – as featured in Powell & Pressburger’s 1945 film I Know Where I’m Going

[xvi] From, Haunted Memory: The Cinema of Victor Erice by Adrian Martin, Cristina Álvarez López, 2016, 13 minutes), which I came across as an exceptional extra on an outstanding film: El Sur (1983) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0084740/. The short video essay is also available to watch at: https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/video/video-haunted-memories-cinema-victor-erice

[xvii] Two recent attempts to escape from parsimonious reality arise towards the end of both http://internationaltimes.it/devon-and-derby-an-english-journey-digression/ and: http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-6/

[xviii] As Wim Wenders has Bruno phrase it in Kings of the Road (1976): A road movie set in a divided Germany whose protagonists are haunted amongst other things, by American music, films and attitudes.

[xix] A pretentious-looking but useful word: https://hyperdiegesis.wordpress.com/2014/07/01/the-hyperdiegesis/

[xx] For X amount of petrol bought, they could obtain a Smurfs figure for the kids: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Smurfs_merchandising

[xxi] I’m afraid the Pet Shop Boys were a complete blank to me, but aren’t we supposed to see the popularity of Sparkle Motion as sick/satirical? Sexualized pre-teens introduced by a pedophile and cheered on by their community! Just about sums up the misdirection and blandly degenerate excesses of consumer society. While the lyrics of West End Girls aren’t exactly poetry, the tone is sarcastic and observational, i.e. too clever. The triumphal, inclusive mindlessness of Notorious, is more apposite.

[xxii] Just as I was only 6 when Van Morrison’s ‘Beside You’ (1968) was released – a song that became so important to K & I, 20 years later https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ke27QakSPxM

[xxiii] http://internationaltimes.it/things-behind-the-sun-a-digression-on-memory-trauma-and-mystery/

[xxiv] As with most period films, certain aspects of Donnie Darko are more in keeping with the time in which it was made, than the time in which it wants to be set. Some of the jargon and expressions definitely wouldn’t have been understood in the Honiton of 1988, while by the time we first saw the film in Taunton in 2003, my eldest son – roughly Donnie’s age at the time and not far off in temperament (minus the “emotional problems”) – would have had no problem with the argot.

[xxv] Donnie’s girlfriend (played by Jena Malone) in the main timeline of the film. When he turns back the clock, she no longer quite knows him.

This sense of parallel possibility is also something which struck me about the film – of missing people in time, of the paths we did not take:

“But just as such a resolve was becoming firm, he would see his future self – was it his future self that he had been watching? – cycling or in some way passing through the edges of these areas, ten years on, from somewhere else . . . How devastating would the blankness be that would surely come upon him then? How far away that lost land of opportunity – a bright circle of sand and green leaves, or the bay through an arch at the end of an ever-darkening tunnel.” From Maze End, chapter 8, Undying Love.

[xxvi] Ibid: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ke27QakSPxM

[xxvii] From the 1982 version of The Bow.

[xxviii] I frequently confuse fictional characters and situations – particularly of my own invention – with ‘real’ people and events. The Quay Royal of Certainty Under the Rose for example, has become if anything, more real to me than the early 1980s Bideford without which it could not have existed. A far wider example would be all those visitors to London who search for 221b Baker Street, honestly believing that Sherlock Holmes actually dwelt within.

[xxix] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4riivOFlhIU (12:52) 08. Gretchen Ross

[xxx] Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to trace the composer.

[xxxi] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0166921/?ref_=nm_flmg_act_83

[xxxii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4iZ13grIFH4 at 2hrs 10 minutes for approximately 3 minutes.

[xxxiii] As you must disregard the MacGuffin of the Glueman in A Canterbury Tale (1944) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MacGuffin

[xxxiv] Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1987) is another film partly about the tragedy of lives passed over. Based on the Marquez novel, it achieves a slightly haunting quality thanks to the slow-paced exotic atmosphere and the (albeit endlessly repeated) poignant music. What it lacks is a clear focus. Alternating between four main characters, it fatally dilutes all of them. A contrast between the isolated and beautiful white house with pristine Jaguar XK 120 outside, and the same decayed location 27 years later, the car rusted away having never moved, carries more emotive weight than anything human – especially when Rupert Everett and Ornella Muti, have only had flour spilt on their hair to indicate the passing decades. Aristo Everett even walks the same!

[xxxv] A simplified cover of Tears for Fears Mad World by Michael Andrews & Gary Jules which changes the tone entirely. Despite the A+ lyrics, the frenetic original with cackling background instruments and fairground sounds certainly wouldn’t fit the film.

[xxxvi] A low budget version of Random Harvest’s fabrication.

[xxxvii] The young “man with the pretty eyes” was how we used to describe him. Sadly, I discovered much later (via IMDb), that Gerry Sundquist took his own life by jumping in front of a train at Norbiton station in 1993, just about when K & I were watching The Mallens on video (slowly, I hasten to add – we never binge). Writing a fan letter to Juliet Stevenson in the mid-nineties after also seeing her in The Secret Rapture (1995) I had a very nice handwritten reply saying how pleased she was that someone had written an enthusiastic letter about her first ever filmed part in The Mallens.

[xxxviii] Link as above: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4iZ13grIFH4

[xxxix] Judging by its high IMDb score, many people must appreciate Random Harvest, but do they just soak up its tragedy with a box of tissues and then go back to normal?

[xl] If art is life with the boring bits cut out (a variation on Hitchcock’s dictum), then memory is quite capable of disregarding the drudgery of life, its materialism and bureaucracy.

[xli] It also appeared to be shared most obviously by my dad, who while he grew impatient of any kind of conversational ramblings (except his own – and what’s unusual about that?), had endless patience for whatever obscure ponderings arose from The London Feeling. This tolerance and even enthusiasm, led to our tradition of epic walks across various parts of London.

[xlii] From Maze End: “When he was lucky, other places, moments or feelings, green paths to shanty sheds, would give him a “London atmosphere” – though what exactly this was, had remained impossible to define. Enhanced by touch, it might flow from expanses of red brick in hot sunshine. It could arise from summer allotments and the tangle of runner beans climbing their bamboo frames – red flowers against the green. It could materialise from country cottages and hanging baskets; from market stalls and boring roundabouts . . . As if all these were only limbs and outposts of London – kept essential by the life blood pumped from Albion’s heart!”

[xliii] From an unpublished poem of June 2019, Beautiful Eyes.

[xliv] Aylesbury’s alter ego in Maze End.

[xlv] Some combination of the Maitri, Karuna, Mudita & Upeksha of Buddhism perhaps? These are concisely laid out at https://upliftconnect.com/the-four-elements-true-love/ . . . if you can overlook the dubious illustrations – which if you have any benevolence, should not be difficult.

[xlvi] From The Bow chapter 10b: “To get past this night, slow rock wheel . . . Morning lights into the world of flawed people and flawed self and takes away the memory-feeling of the pure centres of people. Here in daylight they cannot work. Here they only make it clear, how much smaller are our whole life stories.”

[xlvii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technopoly – a 1992 book by Neil Postman that I’ve yet to fully absorb, defines a Technopoly as “a society in which technology is deified”.

[xlviii] What’s so sad for children today, is that this conformism is thrust upon them at an ever earlier age. People my age had the dangers of TV, later generations the computer; now the mobile device, rarely switched off, follows them around, undermining or destroying the freedom they might have had, often convincing 6-year-olds that they’re teenagers and teenagers that real life is elsewhere.

[xlix] Or is this ‘intensity’ I endlessly go on about, strictly limited to people of a certain temperament – a quality or flaw not appropriate for society as a whole? In society, does the quest for ‘intensity’ only lead to discontent – to a kind of ego-materialism which endlessly dismisses practical life, compromise, relationships and so on, always, in pursuit of something ‘better’? Should there be a disclaimer on intensity: DON’T TRY THIS AT HOME?

[l] From Maze End, Chapter 16, A Quiver of Arrows/Revisited Islands: “Unseasonably for late April, the weather had been hot and sunny – he could’ve been alone on an island in the Cyclades. Beyond the few dusty tracks and small-leaved, densely grown hedges protecting the flower fields from the prevailing wind, was an area of gorse and rocky moorland. Short turf between granite tors – as though a distinctive zone of Dartmoor had been broken off and dropped into a royal blue sea. In dazzling contrast to the deep blue filling the horizons, all the gorse was in full bloom, blazing yellow: the smell was overwhelming, as if soft turf and rock, covered a giant spice cake.

Just fascinating and I ADORE these paintings!! Superb

Comment by Andy on 3 April, 2020 at 6:34 pm[…] [xiii] See the latter part of: http://internationaltimes.it/donnie-darko-a-digression-on-universality-and-inevitable-nostalgia/ […]

Pingback by Bomb Damage Maps – A West London Digression . . . | IT on 14 June, 2020 at 2:18 pmI’ll never look at coconuts the same way!

Comment by Martin on 27 December, 2022 at 7:07 pmSeriously, though, thay could become my new association, maybe forever, or maybe until another experience ‘attaches’ itself to the fruit…