L’agent leve son baton blanc, Jumble Hole Clough (Jumble Hole Clough)

The Duke of Wellington, Derek Bailey / John Stevens (Confront Recordings)

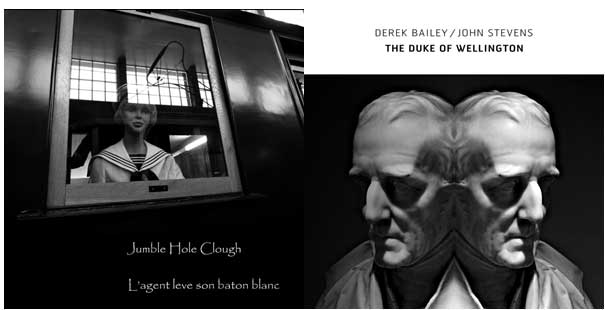

The art that goes with the latest Jumble Hole Clough album, L’agent leve son baton blanc, is an image of a mannikin in a sailor suit staring out of a window at an interior we see reflected in the glass, which itself includes windows. It’s hard to read the expression on its face, but, of course, whatever it might be thought to represent, mannikins are devoid of feeling. Any emotions conveyed through the expression on their faces are merely in our minds, not theirs, a trick of construction – just as any expression of emotion through music is a trick of construction. It is, I think, a very appropriate image for the album: I’m not sure why but it’s partly, I’m sure, something to do with all this and, I guess, more simply, because mannikins and dolls, like JHC, always project a slightly edgy, disconcerting aura.

I was talking to Colin Robinson (aka Jumble Hole Clough) the other day about the origin of the title. It was, he said, simply a phrase used in his school French lessons. L’agent leve son baton blanc et les autos s’arrête. He told me how if a phrase sounded good, he’d use it. He went on to say how important it was to get the lyrics down without overthinking them. Let your mind freewheel. Work fast. You only have to say l’agent leve son baton blanc over a few times to get a feel for the rhythm and see how it might appeal. The words find their way into the third track, ‘et les autos s’arrête’, both in French and English, though the more surreal English version is hardly a literal translation: ‘the policeman waves his magic wand and the cars all disappear’. JHC lyrics are nothing if not surreal, although what comes over to the listener as Surrealism, Colin said, usually has its roots – albeit obscurely – in his experience of real life.

You could describe L’agent leve as haunted by the past. Strictly speaking, we’re not talking about hauntology here, although the music often has a dreamy quality: what haunts this music is not a ‘futuristic’ future that never came to pass, but a past that’s in danger of being forgotten, musical gestures that – as certainly as Vesta curry – belong to a particular time and which, now, speak of that time at least as much as, back then, they moved us emotionally. With hauntology we find ourselves mourning the loss of a future, whereas with this we find ourselves mourning the loss of an admittedly – in many ways – imperfect past, although not, I hasten to add, in any nostalgic way. The end result is anything but nostalgic. Musical gestures and textures from the 1960s and 70s find their way into the music here as ‘found objects’, much like the phrase from the French lesson. And it’s less memory lane, more ghost train. If I had a phantasmagorical dream about my teenage years and the gigs my mates dragged me to at Birmingham Civic Hall, this could be the soundtrack (if I had to choose one track for the purpose, it would be the aforementioned third). JHC describes itself as ‘music influenced by the landscape, industrial remains and experiences around Hebden Bridge’, but I wonder if this time Colin has produced something more inward-looking. I guess, in a way JHC always was: after all, if you work fast, trust word associations and dreams (the earlier album, Don’t Say Nowt is based on dreams), you will. Perhaps I’m reading too much into it, but maybe it’s significant that the central found object to this album isn’t the bells in the valley or the crows in the field but a memory of learning a language over half a century ago.

There again, I guess you never know what you’ll pull out next from a jumble hole. Talking of found objects, as we were, the biggest here is Steve Lacey Marsden’s story (‘The playground by the abandoned mill’ – definite overtones of the Hebden Bridge environs there). It’s the sort of thing James Joyce might’ve written, had he been from West Yorkshire instead of Ireland. ‘History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake’, as Joyce’s fictionalised, younger self says in Ulysses. Dedalus took himself far too seriously but then I probably did at that age. Robinson, being older and wiser, doesn’t: his starting-point is personal history (although the implications are wider) and what we get, rather than nightmare, is wry acceptance. As he says in track two, ‘From Belgrade to Zagreb by bus’:

I don’t know what you were expecting:

it probably wasn’t this.

I don’t care what you think:

this is what it is.

Realistically, there is no alternative: we bring our pasts to the present and what we do in the present becomes the past; the past is both imperfect and unchangeable. It’s a bleak thought, but, thankfully, the vagaries of free association don’t allow one to take it all too seriously. As he sings in the first song:

He was praying in the tabernacle

genuflecting while fumbling his tackle

We’ve all been there – metaphorically, at least.

There are some real treats here: ‘Monsieur Thibaut est ingénieur’, harks back, I suspect, not only to another French lesson, but to Colin’s past preoccupation with generative music (it either uses such systems, or is heavily influenced by them). ‘Sleep Apnoea’ is wonderfully evocative of something – uncertainty itself, perhaps. There’s a truly magical moment in the middle of ‘You can whistle down the wind’. ‘A man said hello to me’, like ‘et les autos s’arrête’, harks back to another, more recent JHC preoccupation, namely, building longer forms. ‘Squally Showers’ is the kind of track that, if it cropped up on the radio, might get people checking out JHC. The final track, ‘it’s time to go home’ is a light-hearted jam, although the words, and the final ‘goodbye’, are perhaps an allusion to mortality, especially given the earlier tracks’ allusions to the other end of life.

I make this the forty-ninth JHC album. I was going to say it’s great that an artist can still put out their best work after producing so much, but, in fact, it’s not surprising: it’s often the way of things. There are places you can only reach by putting years of creative work and Colin Robinson has reached them. Have a listen!

For the second time in a matter of weeks, here we have an opportunity to hear more from guitarist Derek Bailey, this time performing with John Stevens. Neither man should need much by way of introduction: both were seminal figures in the world of free improvised music as it took shape in the 1960s and 70s. Thanks to Michael Gurzon’s recording, here they are, in 1989, performing together at The Duke of Wellington in London.

The first track, ‘I’m Alright Actually’, begins with a series of slippery shapes, the noise-elements of Bailey’s guitar merging with those of Stevens’ percussion in a non-stop stream of invention. The music reaches a point of stasis before moving off into a series of angular shapes which give way to a stream of more slow-moving ideas. There is always a sense of restlessness though, a feeling that, at any moment, things might get more chaotic, which, inevitably, the do. The music ebbs and flows, but the inventiveness and the sense of restless energy is always there. A few seconds of applause have been left in at the end, which really captures the ambience of the venue (the same goes for both the other tracks, too).

The second, ‘What’s the Time?’, begins with more spacious, harmonic-dominated ideas from Bailey, in dialogue with Stevens’ ‘pocket trumpet’. Almost seven minutes in, the music becomes more dense and agitated. Towards the end it almost comes to rest in another section dominated by harmonics, then tries to build up to a climactic moment before subsiding back into something more reflective.

The third , ‘More’, starts with some shifting chords from Bailey backed up with some fragmentary interventions from Stevens, after which things quickly become more sustained and fast-moving. About 6 minutes in, the pace drops and we’re treated to a strikingly lyrical piece of playing from Bailey.

Anyone interested in improvised music will want to listen to this, not just on account of its undoubted historical value, but because of the music itself. It’s both a great listen and a text-book example of how to make up music as you go along.

Dominic Rivron

LINKS

L’agent leve son baton blanc:

https://jumbleholeclough.bandcamp.com/album/lagent-leve-son-baton-blanc

The Duke of Wellington:

https://confrontrecordings.bandcamp.com/album/the-duke-of-wellington

.