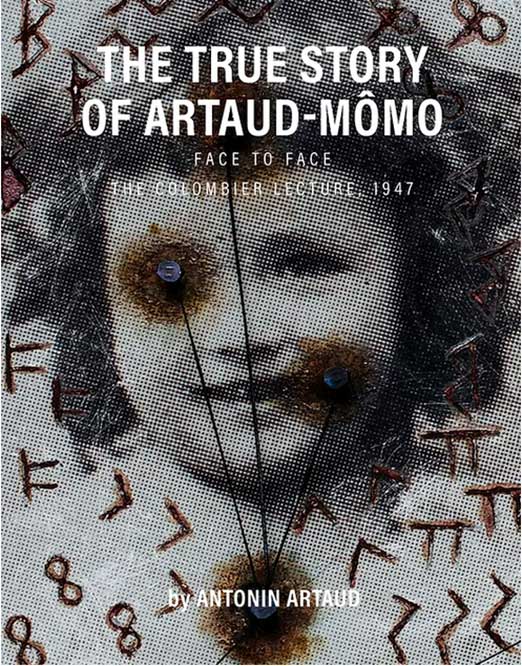

The True Story of Artaud-Mômo, Antonin Artaud (Infinity Land Press)

It is strange what chance throws up: this new Artaud book arrived in the same postal delivery as an anthology of Radical Christian Writers. So, on the one hand there are the likes of John Milton and William Blake being mystical, along with faith-inspired social activism from The Levellers, Dorothy Day, Steve Biko and Daniel Berrigan; and on the other the obsessive declamations of magician, writer and artist Antonin Artaud, who is fascinated by shit, piss, masturbation, sex and other bodily functions, especially his own.

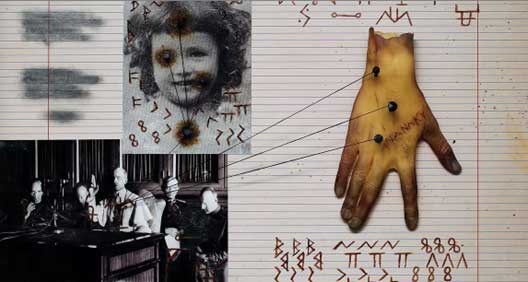

This new volume from Infinity Land Press is a beautifully produced and illustrated hardback edition and sits well within what the publishers claim is ‘a realm deeply steeped in pathological obsessions, extreme desires, and private aesthetic visions’, an intriguing and perverse list. The book includes reproductions of pages from Artaud’s own notebooks as well as new collage art by Martin Bladh and Karolina Urbaniak, a contextualising foreword and afterword, along with a bookmark.

Artaud was always an extreme artist, although both his poetry and drama manifesto, The Theatre of Cruelty, had an important and lasting impact on the arts in the 20th Century and beyond. His appropriation and reinterpretation of various cosmologies, surrealism, occult writings and practices not only informed his writing but also his theatre and film work, which he regarded as a form of magic and ritual, a way to shock and entrance an audience. His artistic obsessions with the extremes of self-expression paved the way for performance art before that existed: screams and sighs, abuse and verbal harassment, sensual overload and physical sensation…

All of which helped maintain the myth of the tortured artist, the lone genius and visionary, the misunderstood (secular) prophet who can articulate what no-one else can. He may not have chopped his ear off, like Van Gogh, but Artaud aspired to ‘the body without organs’ (a phrase later adopted by philosophers), a pure form of life and experience that remained apart from the filth, refuse, banality and constraints of everyday life.

For Artaud, his life included long period of internment in lunatic asylums, which did not help his physical or mental wellbeing. He was given electroshock treatment and remained convinced that he had died during the treatment, and that afterwards he remained in a permanent state of shock and pain, and that his soul had been assassinated.

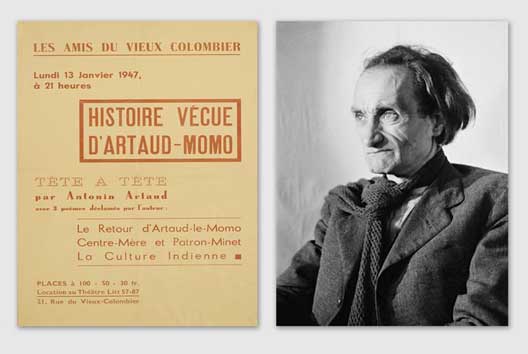

This book, one of many books by and about Artaud which have helped swell his ever-expanding posthumous bibliography, focusses on a lecture he gave in Paris at the beginning of 1947, a little over a year before he died. Although he had prepared extensively for this event, he ended up improvising much of what he said; the Introduction describes the actuality of what occurred, cleverly making use of contemporaneous reports by those who were present, such as André Gide, as well as newspaper reports and Artaud’s own letter about the lecture to André Breton.

The bulk of the book is, of course, Artaud’s own writing. There is the text of three notebooks he took along to the lecture, as well as what are called ‘Preparatory Texts’ here. It is unclear how much of the notebook material was actually used, or whether it was always designed as a prompt for the event. The preparatory work makes it clear that Artaud was already resisting and deconstructing the idea of a lecture or performance:

I am not going to give an elegant lecture and I am not going give a

lecture.

I don’t know how to speak,

when I talk I stutter because someone’s eating my words,

I say they’re eating my words

and to eat you need a mouth, etc.

although he clearly craved an audience:

So, you see, I wanted to see a few people here because I have something

to say

and I want to be heard and I want you to hear me.

What Artaud really wanted was to be believed, about how he had been hurt and tortured and imprisoned, about magic in the world that had entranced and attacked him, about the non-existence of god, religion or the mystical, despite proclaiming that he had been ‘fighting against spirits for 31 years’. He maintained, however, that he and poet Gérard Neval had ‘come to the same conclusion’:

that there is no spirit

no occult,

no world beyond,

that everything beyond the dead is here,

in the hand, the foot, the arm.

At base, Artaud is questioning ‘what is the world of reality?’ but it is unclear if he regards the conscious and subconscious as the essence of man or a by-product of the bone and flesh and sinews he is condemned to inhabit and then vacate. His physical body has endured both physical and mental pain, both inflicted by society, which he tries to resist by encouraging others to recognise that they are ‘a magician who doesn’t know he’s one’ and should inhabit ‘the plane of depravity’ where, he claims, can be found ‘the real fabric of life’.

Whether we regard Artaud as mad, revolutionary or merely a provocative writer, actor and performer, his convoluted experimental texts, his screams, spells and incantations remain, questioning the very nature of reality and how society works (or doesn’t). Doesn’t the following sound rather familiar and still true today?:

I, Antonin Artaud, say, that except for the few rare friends I know,

we are all surrounded by lunatics and scoundrels by virtue of some

sinister schemes that are both simplistic and also supremely criminal

and wanton.

Whilst his mutually embracing and rejecting magic, liturgy, mysticism and science is confusing, Artaud seemed to deliberately engage with contradiction and confusion as a way to answer the biggest question of all: ‘What does it mean to feel you exist?’, which is perhaps a question we have all asked despite knowing, as evidenced here, that there are no answers to that question or many others.

What is life, where are we, what is there? are the questions I keep

asking myself

.

Rupert Loydell

The Infinity Land Press website can be found here.

.