Throughout their career, Pink Floyd treated sound as something unstable and open ended, something that could suggest ideas and emotions without explaining them. Their connection to the avant garde lies less in provocation and more in a sustained interest in process, perception, and ambiguity. This approach allowed their music to evolve slowly, absorbing new ideas without ever settling into a fixed identity, blending avant garde tendencies with melody, atmosphere, and psychological depth.

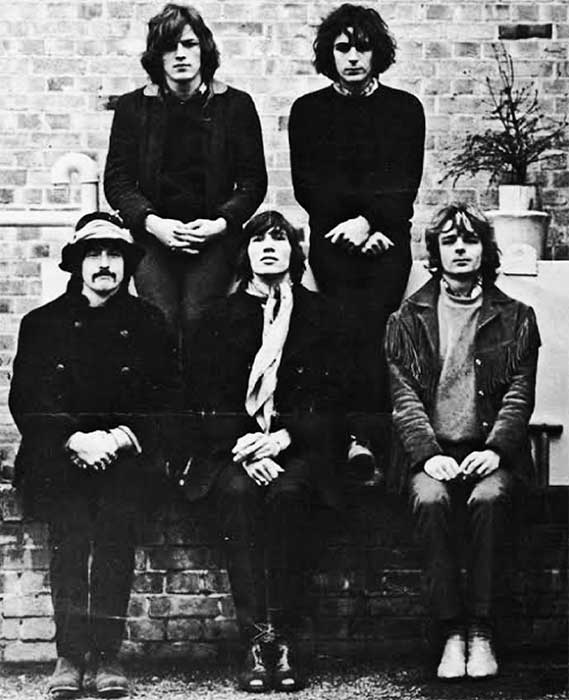

Their beginnings in the mid 1960s London underground are essential to understanding this outlook. Pink Floyd emerged from a cultural environment shaped by art schools, shared houses, and informal happenings where boundaries between disciplines were deliberately blurred. Music existed alongside painting, experimental film, poetry readings, and light shows, often happening at the same time rather than in isolation. At venues such as the UFO Club, performances were immersive environments rather than conventional concerts. Liquid light projections flowed across walls and bodies, sound systems were pushed to their limits, and repetition was used to alter attention and perception. Pieces could stretch far beyond expected length, sometimes losing any obvious structure altogether. Improvisation was not decoration but method. In this underground scene, music was provisional and responsive. Mistakes were absorbed, chance was welcomed, and duration mattered as much as melody or rhythm. These conditions formed the foundation of Pink Floyd’s experimental instincts and shaped their understanding of music as experience rather than product, hinting at avant garde approaches without abandoning accessibility, and reflecting the wider counterculture that celebrated experimentation, fluidity, and shared experience.

Syd Barrett was central to shaping this early identity, both musically and culturally. He was not simply a songwriter but a figure who embodied the openness and fragility of the underground itself. Barrett understood pop music deeply, but he seemed instinctively unwilling to treat it as stable or authoritative. His songs often feel as though they are gently resisting their own form. Chord changes arrive unexpectedly, rhythms loosen or falter, and lyrics drift between playful imagery and quiet menace. His vocal delivery reinforces this instability, sounding conversational one moment and strangely detached the next. Barrett was also deeply interested in sound as texture. Echo, distortion, and feedback were expressive tools used to blur edges and unsettle familiarity. His approach suggested that songs were not finished objects but living things, capable of shifting shape each time they were performed. Barrett’s work exemplifies the band’s earliest flirtations with avant garde thought, showing that experimentation could exist within a pop sensibility.

Before the first album, this approach was already visible in the band’s early singles. Arnold Layne, released in 1967, is a striking example of how Pink Floyd combined pop accessibility with unsettling subject matter. On the surface it is catchy and melodic, with a structure that fits radio expectations. Yet its narrative, centred on a socially marginal figure who steals women’s clothes, introduces ambiguity, humour, and discomfort. The song neither condemns nor explains its subject. Musically, its unusual harmonic movement and prominent organ line disrupt the smooth flow of conventional pop. Arnold Layne demonstrates how Barrett used everyday oddness as a way of unsettling normality, turning a three-minute single into a quiet act of defiance against lyrical and musical convention, hinting at avant garde experimentation in a mainstream form.

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, released in 1967, captures the moment when underground experimentation briefly intersected with commercial visibility. Beneath its surface charm lies a casual disregard for conventional form. Songs frequently change direction without preparation, as if following shifting attention rather than a plan. Instrumental passages expand beyond their apparent purpose, prioritising texture and atmosphere over progression. Studio effects create space and disorientation rather than polish, reinforcing the sense of instability. Interstellar Overdrive remains a defining statement, reducing rock music to raw elements, a riff, noise, silence, and gradual reconstruction. The track unfolds like a live experiment preserved on tape, directly reflecting the band’s extended improvisations at underground venues. Even the album’s shorter songs resist neat closure, often ending abruptly or unresolved. Piper presents experimentation as instinctive and playful, rooted in imagination and curiosity rather than discipline, showing early engagement with avant garde ideas.

Barrett’s departure marked a profound rupture. His withdrawal removed not only a songwriter but the unstable centre around which the band had revolved. A Saucerful of Secrets, released in 1968, documents a group searching for a new collective identity while still carrying the weight of recent loss. The album’s unevenness is part of its meaning. Songs feel tentative and fragmented, reflecting uncertainty rather than confidence. The title track is especially important. Beginning in near silence, it slowly accumulates sound, moving through dissonance, noise, and rhythmic pulse before reaching a solemn choral conclusion. Meaning emerges through duration, contrast, and massed sound rather than lyric or narrative. The piece resembles a ritual or process, emphasising collective movement and emotional release. Elsewhere on the album, traces of Barrett’s influence linger, but they are refracted through a band learning how to function without him, carrying forward an experimental and avant garde spirit in a new direction.

More, released in 1969 as a soundtrack, continues this exploratory phase in a quieter and more restrained form. Rather than asserting itself, the music functions as atmosphere and emotional colouring. Many tracks are brief, understated, and unresolved, existing as fragments rather than complete statements. Acoustic simplicity sits alongside drifting electronics, creating a sense of gentle dislocation. Repetition plays a central role, creating suspension rather than development. Silence and space are given unusual importance, allowing the listener’s attention to wander. Some tracks, such as Green Is the Colour and Cymbaline, mix folk simplicity with experimental textures, highlighting the band’s growing interest in mood and environment rather than melody alone. More shows Pink Floyd refining their ability to suggest rather than declare, revealing a maturity in restraint that contrasts with their earlier, more chaotic experiments, all while maintaining an experimental undercurrent reminiscent of avant garde thinking.

Ummagumma, also released in 1969, stands as one of the most revealing and uncompromising documents of Pink Floyd’s experimental process. The live half captures the band at full volume, emphasising distortion, repetition, and extended improvisation. Familiar material is dismantled and reshaped, transformed through endurance and gradual variation. These performances recall the physical intensity of the underground scene and prioritise immersion over clarity. The studio half removes collaboration entirely, isolating each member within their own sonic space. These pieces function as personal sound studies, exploring noise, texture, silence, and unconventional structure. Some ideas feel deliberately awkward or unresolved, and that discomfort is central to the album’s value. Tracks such as Sysyphus, composed of four distinct movements, explore duration, thematic development, and sonic layering in ways that foreshadow later progressive experimentation. Ummagumma refuses polish and coherence, presenting experimentation as exposure and risk, drawing on avant garde principles while remaining rooted in rock.

Atom Heart Mother, released in 1970, marks a turn toward scale and extended form. The title suite combines rock instrumentation with orchestra and choir, not simply to create grandeur but to explore contrast, density, and emotional range. Themes recur in altered states, sometimes fragmented, sometimes submerged beneath massed sound. The piece moves between pastoral calm and overwhelming intensity, resisting clear narrative or resolution. Its ambition lies in holding opposing moods within a single structure. Brass and woodwind passages interplay with guitar and organ textures to produce a tension between serenity and unease. The shorter tracks on the album, including Fat Old Sun and If, provide contrast, emphasising intimacy, domesticity, and space. Atom Heart Mother treats the album itself as a continuous field of exploration, balancing excess with restraint, and demonstrates the band’s growing skill in combining rock with orchestral and experimental techniques, hinting at avant garde methodology without abandoning accessibility.

Released in 1971, Meddle represents a pivotal transitional moment between the large-scale experimentation of Atom Heart Mother and the fully immersive cohesion of The Dark Side of the Moon. The album balances rock energy with long-form compositional ambition. The side-long epic Echoes dominates the record, stretching over twenty-three minutes and moving through multiple musical landscapes. Beginning with aquatic-inspired sound effects and gradually building a hypnotic motif on guitar and keyboards, Echoes shifts from contemplative passages to climactic intensity. Its use of space, call-and-response motifs between instruments, and gradual layering of vocal harmonies demonstrates the band refining ideas first explored in A Saucerful of Secrets and Ummagumma. Other tracks, such as One of These Days, introduce more direct rhythmic propulsion while retaining subtle experimentation with tape effects, instrumental layering, and dynamic contrast. Meddle shows the band moving toward longer, more unified pieces that communicate conceptually without relying on narrative lyrics, continuing their avant garde-inspired approach while embracing a more polished, cohesive style.

The next album, 1972’s Obscured by Clouds captures Pink Floyd at a quietly adventurous moment. Made quickly as another film soundtrack, the album feels loose and instinctive, as if the band were testing ideas without worrying too much about polish. That freedom gives it an experimental edge, even when the songs sound simple on the surface. The tracks drift between moods rather than settle into one place. Synths slide in and out, guitars shimmer rather than dominate, and rhythms feel more suggested than fixed. There is a sense of movement throughout, like passing landscapes seen through a window. Short instrumentals sit next to songs with plain, almost fragile lyrics, creating an unsettled but curious flow. Much of the experimentalism lies in how the band treat sound as texture rather than statement. Electronic tones are used sparingly but boldly, often carrying the mood instead of the melody. Songs fade in and out without clear endings, and ideas appear briefly before dissolving. This approach reflects a band more interested in atmosphere and feeling than in traditional song structure. What makes the album feel avant garde is not shock or excess, but restraint. Pink Floyd strip things back and let atmosphere do the work. In doing so, they sketch ideas that would soon grow into something bigger, while still standing as a strange and thoughtful piece in its own right.

The Dark Side of the Moon, released in 1973, represents the most refined integration of experimental techniques into a coherent whole. Often described as accessible, it is built on methods drawn from avant garde and electronic sound practice. Tape loops, synthesiser drones, processed speech, and environmental sounds are woven into a seamless structure. Tracks bleed into one another, shaping time as a continuous experience rather than a sequence of separate songs. Spoken voices appear as fragments of thought rather than commentary, detached from identity and functioning as shared inner dialogue. Effects such as clocks, heartbeats, and cash registers ground abstraction in physical sensation. Concepts of mental strain, mortality, and human experience are explored through musical texture, rhythm, and tonal shifts, creating an immersive experience where experimentation becomes integral to emotional impact rather than novelty.

Wish You Were Here, released in 1975, turns inward, focusing on absence, memory, and emotional distance. Long instrumental passages unfold slowly, allowing repetition and space to carry weight. Studio effects suggest mediation and separation, as if the music itself is struggling to connect. Tracks such as Shine On You Crazy Diamond pay homage to Barrett, blending melancholy lyricism with layered sonic textures that stretch over a long period of time, highlighting the band’s interest in emotional resonance through extended form. Themes of disconnection and industry critique are interwoven with lush soundscapes and subtle rhythmic experimentation. The album’s experimental quality lies in restraint and patience, trusting atmosphere and texture to convey feeling more powerfully than explanation.

Animals, released in 1977, adopts a harsher and more rigid musical language, reflecting social tensions during the late counterculture period and the broader cynicism emerging as the optimism of the 1960s dissipated. Extended tracks such as Dogs and Pigs (Three Different Ones) unfold over long arcs, built on repetition, density, and slow transformation. The music exerts pressure rather than offering comfort, mirroring themes of control, alienation, and social hierarchy. Tension builds through rhythmic insistence, sustained chordal structures, and layered instrumentation. Experimentation here lies in how musical form itself becomes an expressive tool, conveying the emotional weight of social critique through structure, texture, and duration rather than conventional melody or harmony.

The Wall, released in 1979, represents a shift toward narrative and psychological exploration. Often described as a rock opera, it functions more accurately as a fragmented mental landscape. Recurring motifs, abrupt perspective changes, spoken dialogue, and intrusive sound effects collapse the boundary between inner thought and external reality. Tracks like Comfortably Numb combine virtuoso performance with immersive studio layering, creating moments where technical skill and atmosphere converge to communicate inner isolation. The album uses sound to enact emotional and psychological fragmentation, drawing on techniques associated with theatre and radio art to place the listener inside a constructed mental space.

The Final Cut, released in 1983, continues this trajectory and strips the music back to its emotional core. Sparse arrangements, extended spoken passages, and deliberate pacing allow silence and restraint to speak. The album avoids release or resolution, leaving grief, anger, and disillusionment exposed. Its experimental quality lies in its refusal of spectacle, using understatement and fragmentation to convey emotional weight. Tracks like The Fletcher Memorial Home combine orchestral arrangements with minimalistic rock instrumentation, showing how experimentation can support narrative and theme rather than dominate it, closing a trajectory that moves from psychedelic underground and avant garde experimentation to political, personal, and social reflection.

Following a hiatus from studio albums, Pink Floyd returned with A Momentary Lapse of Reason in 1987. The album reflects the lingering influence of counterculture ideals of openness, reflection, and collaborative exploration, even as the band adapted to a more technologically advanced, synthesiser-driven sound. Themes of memory, isolation, and existential concern are present throughout, and the music often feels like a space for contemplation, echoing the immersive, atmospheric tendencies developed decades earlier, while responding to the anxieties and technological culture of the 1980s.

The Division Bell, released in 1994, continued the focus on reflection and human connection, exploring communication, unity, and the tension between isolation and understanding. Its layered textures, atmospheric production, and expansive instrumental passages echo the meditative experimentation of the counterculture era, while adapting it to a mature, postmodern sensibility. Tracks such as High Hopes revisit ideas of transition, nostalgia, and emotional resonance, highlighting how the band retained an experimental ethos even late in their career.

The Endless River, released in 2014, serves as a contemplative coda to the band’s career. Largely instrumental, it draws from sessions recorded during The Division Bell and revisits ambient textures, atmospheric soundscapes, and improvisatory passages. Its reflective nature and focus on mood and space recall the immersive environments of the 1960s underground, carrying forward the counterculture spirit of exploration, openness, and shared emotional experience. It functions as both homage and final exploration, closing a circle that began with Syd Barrett and the UFO Club.

Pink Floyd’s originality lies in treating experimentation as a long conversation rather than a phase or statement. From the London underground of the 1960s and Syd Barrett’s fragile imagination, through the risk taking of More and Ummagumma, the ambition of Atom Heart Mother and Meddle, and the immersive precision of The Dark Side of the Moon, experimentation remained central. Their engagement with the avant garde was never about rejecting the listener but about trusting them, believing that sound could carry thought without explanation, while the later works reflected the counterculture’s evolution into a more questioning, critical, and reflective stance across decades of social and musical change.

By inviting listeners into spaces where meaning remains open and unresolved, Pink Floyd created a body of work that continues to resist final interpretation. That openness, shaped by curiosity, risk, and patience, remains at the core of their lasting significance.

Ade Rowe

.