Original Graphic Art ‘On the Phone’ specially created by Amber Pletts

Saturday 14th February 2026 for Ma Yongbo 马永波 and Helen Pletts’ 海伦·普莱茨 Response Poetry.

On the Phone 打电话

“Where are you?” which suggests

people may not be where they’re supposed to be: home or at work

Escape or pilgrimage?what does it matter if we’re on the way

“What’s up?” Then say something

But with phone bill cheapest at midnight

enthusiasm drops to zero degrees. A call from God

shakes the dark rotary phone, nobody answers

Something perishing like shining particles in rising river

may be the reason for the call

“Nothing much. Read, go to work,

write something. Let’s fix a date for meeting”

Some other day, other day. See you.

Putting down the receiver, people keep walking

but unlike Jack Kerouac who spanned

the whole dark land searching for meaning

Go upstairs. I write

“Cloudy and then sunny. The world is there.”

Now somebody is waking up in a stranger’s bed

1998

Response Poetry By Ma Yongbo 马永波

Response Poetry Translated by Ma Yongbo 马永波

打电话 On the Phone

“你在哪儿呢?”这说明

人们不在惯常称之为家和单位的地方

逃亡还是朝圣?总之是在路上

“有事儿吗?”那么说些什么吧

电话费在午夜降到最低,热情

也降到零度,上帝的电话

在黑暗的支架上震动,无人倾听

打电话的理由是一些事物的消失

像上涨的江水中发亮的东西

“我没干啥。看书,上班,

写点儿东西。找机会聚聚吧。”

那么改天吧,改天聚聚。再见

放下电话,人们继续在路上

但不是凯鲁亚克那样,去跨越

整片黑暗的大陆,寻找一些意义

(或者词语)。上楼,我接着写

“今天天气阴转晴。世界存在着。”

有人从陌生人的床上醒来

1998 马永波

the phone reimagining itself as a third eye, or turn off the phone—for Yongbo

written in response to his poem ‘On the Phone’

you are where the phone tells you,

only the phone knows where you are.

Not being a part of the phone

does not mean that you have ceased to connect

to the higher being, which is somewhere in the middle of a dark square

where the latitude is a subtle latino ballad that you always thought

you loved until it broke the silence of the cinema,

repetitive and openly challenging your taste in music,

dropping you into a dark well like a stone

forces it’s way through darkness until it hits the end,

or water slows the speed itself, like a free falling hand

desperately searching into a dark pocket

4th August 2025

written to make us both smile because we have both been ill

Response Poetry By Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨

Response Poetry Translated by Ma Yongbo 马永波

手机将自己重新想象成第三只眼睛,或者关掉手机

为回应永波诗《打电话》而作

手机说你在哪儿,你就在哪儿,

只有手机知道你在哪儿。

不成为手机的一部分,

并不意味着你已中断与那更高存在的

连接,它就在某个黑暗广场的中央,

那里的纬度是一首柔和的拉丁民谣,你一直以为

自己深爱着它,直到它打破了电影院的寂静,

循环往复,公然挑战着你的音乐品味,

将你如石块一般投入一口深井

奋力穿过黑暗,直至抵达尽头,

或被水流减缓了速度,像一只自由落体的手

在黑暗的口袋里急切地摸索

2025年8月4日

谨以此诗博取彼此一笑,因为你我都在病中

海伦·普莱茨

Cover of Jade Moon, Issue 3

Ivana Milanovic, Editor-in-Chief, Jade Moon magazine

“I created Jade Moon because I believe there is beauty and value in understanding cultures beyond our own. The magazine’s name reflects its mission: jade symbolises virtue, grace and timeless strength, while the moon—universal yet deeply personal—represents reflection, connection and poetic inspiration.Together, they form a vision of cultural exchange, where readers can discover China’s stories and see echoes of their own…The purpose of Jade Moon is simple: to open a window. To allow readers to look beyond borders, discover the beauty of China’s cultural heritage and maybe find inspiration to explore further. Whether you are drawn to mythology, history, literature or the arts, I hope this magazine will spark curiosity, conversation and understanding.”

Ivana Milanovic, Editor-in-Chief, Jade Moon magazine

Ivana Milanović is the founder and editor of Jade Moon, a bilingual magazine dedicated to Chinese culture and traditions, and cross-cultural dialogue in the Balkans. The magazine is written and produced independently in English and Montenegrin, with a focus on history, mythology, literature and contemporary cultural exchange.

She holds degrees in Italian language and literature, cultural mediation, and political studies. Her academic background supports her work in translation, editorial research, and the presentation of Chinese thought across linguistic and cultural contexts.

Through Jade Moon and related projects, she develops participatory cultural formats and regional initiatives that connect readers with Chinese cultural traditions.

She works independently across languages and regions.

Jade Moon Magazine Jade Moon, a bilingual magazine celebrating Chinese culture. From ancient legends to modern voices, each page brings to life history, myths and timeless tales.

FULL CHINESE VERSION OF JADE MOON ARTICLE HERE:

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/iWt6bw5csxfQ1A0n-VniUQ

Echoes of the Soul, Poetic correspondence: Ma Yongbo and Helen Pletts

In Jade Moon’s first two issues, we explored China’s great classical traditions through the Book of Odes and the Songs of the South. This time, we follow that thread into the present asking how one of those long-standing practices — poetic correspondence (赠答诗) — continues to function in contemporary literary life.

From the Tang and Song dynasties onward, poets used exchanged poems to sustain friendships across distance, reflect on shared moments and think together through verse.

These paired works were both personal communications and part of the public literary record. While the historical context has changed, the core impulse behind the form remains recognisable.

The article opens with Ma Yongbo’s work and reflections, before moving to poetic correspondence with Helen Pletts.

Ma Yongbo: A Poet Between Languages and Worlds

Ma Yongbo is one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary Chinese literature — a poet whose work bridges geographies, languages, and literary traditions. Born in Heilongjiang and now based in Nanjing, where he teaches at the Faculty of Arts and Literature, (at Nanjing University of Science and Technology), Professor Ma is widely regarded as a representative figure of Chinese avant-garde poetry and a leading scholar of Anglo-American literature. His career spans four decades of writing, translating and teaching, yet at its heart is a simple belief: poetry is a conversation that can cross all boundaries.

Parallel to his life as a poet, Ma has built a distinguished career as a translator of English-language literature. His translations include many of the most influential Anglo-American poets, among them Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Wallace Stevens, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, John Ashbery. He has also translated major works of prose, most notably Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick — a major translation project whose Chinese edition has reached a wide readership (over 600,000 copies sold).

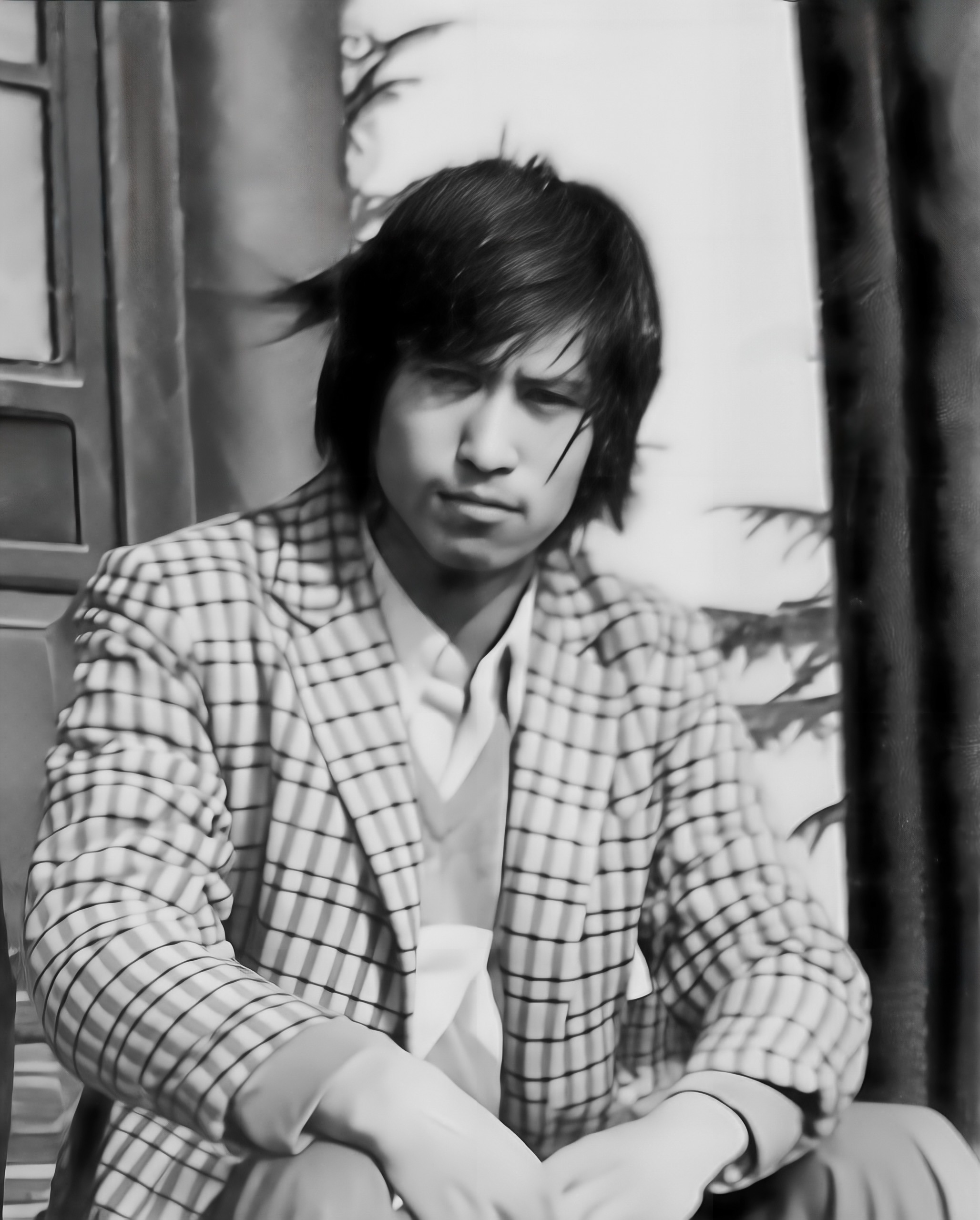

Professor Ma at Xi’an Jiaotong University, where he studied from 1982-1986

Over the years, Professor Ma’s poetry, criticism and translations — more than eighty books in total — have been published widely. In 2024, this body of work was gathered in a four-volume Collected Poems, bringing together over a thousand poems written across four decades. Despite this scale, he approaches poetry with the same openness that has marked his career from the beginning. He continues to take part in readings, collaborations, and exchanges that privilege genuine connection — moments where the focus is not on prestige or theory, but on the shared act of making and sharing poetry.

That openness has led to projects that extend beyond conventional literary boundaries. His recent collaboration with British poet Helen Pletts began with a simple online encounter and developed into a sustained exchange of poems, each written in response to the other. This practice of poetic correspondence has deep roots in Chinese literary history, yet here it unfolds across languages and cultural contexts, showing how inherited forms can remain alive through dialogue.

In many ways, Ma Yongbo’s career reflects a balance between tradition and experimentation, depth and accessibility. He brings a scholar’s knowledge of literary history together with a poet’s attentiveness to the present moment, a translator’s discipline alongside a collaborator’s openness. While his work moves between languages, it remains anchored in the idea that poetry itself offers a shared ground.

Professor Ma, you write, translate, and teach. How do these three roles shape and inform each other in your daily work?

Although my areas of engagement are quite diverse, poetry remains the core of my writing, translation, and research work. Translation serves as an essential complement to writing: it plays a crucial role in maintaining linguistic sensitivity and expanding cultural horizons. Moreover, a poet who can create and think in more than one language gains a richer understanding of the world and adopts more perspectives in judging things, thereby largely avoiding one-dimensional linear thinking—for the world may take on vastly different forms when viewed through the lens of different languages.

The Impact of Writing on Translation and Teaching—

As a translator, my sensitivity to poetic language and understanding of poetics have become unique strengths in my translation work. Firstly, writing experience has enhanced my ability to perceive language. Take my translation of John Ashbery’s works as an example: I adopted a literal translation approach, striving to preserve the original text’s formal structure, word-formation patterns, and sentence structures, rather than overemphasising “domestication” (i.e., adapting the text to fit the target culture’s conventions). This translation strategy stems from my understanding of the essence of poetic language—the form of poetry itself carries meaning.

Secondly, creative practice has influenced my translation choices and philosophy. My main focus is translating Anglo-American postmodern poetry, which is closely aligned with my own creative direction. In the context of Chinese poetry, I have advocated for key poetic concepts such as “narrative poetics,” “meta-poetry,” “pseudo-narrative poetics,” and “objectivist poetics.” These explorations have directly shaped my selection of texts to translate: I tend to choose works that are innovative and experimental in terms of poetics.

In teaching, I believe writing experience allows me to connect abstract theories with concrete creative practice. As Professor of Western Cultural Studies at Nanjing University, I taught a course on modern poetry for 16 years, integrating insights from my own writing and translation into the curriculum to ensure the course was highly targeted and practical. I also transformed my writing experience into a unique teaching method. For instance, I proposed the concept of “difficult writing,” which emphasises the experimental nature and intellectual depth of poetry. In class, I often encourage students to experiment with language and try new modes of expression—because the “craftsmanship spirit” in poetic writing is more of an ethical attitude, one that requires balancing spontaneity, improvisation, and rationality.

The Multifaceted Impact of Translation on Writing

Long-term experience in translating poetry has endowed my own poems with not only the linguistic style of a local (Chinese) poet but also the influence of Western poetic traditions, thereby granting them enduring aesthetic potential that invites repeated contemplation.

For example, through translating Ashbery, I gained a profound understanding of postmodern poetic techniques such as fragmentation, collage, and processuality, which I later integrated into my own creations.

Translation has also provided me with a cross-cultural perspective. The works I have translated span from 19th-century Romanticism to 20th-century postmodernism, and from American eco-literature to contemporary British poetry.

This extensive translation practice has given me a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of Western culture. When translating Walt Whitman, for instance, I delved into his democratic ideals and the “American spirit”; when translating Emily Dickinson, I focused on her religious beliefs and the complexity of her inner world.

Such broad translation experience has allowed me to recognise the characteristics of poetry across different cultural contexts through comparison, enabling me to integrate Chinese and Western poetics in my own writing.

This ability to synthesise cultures ensures that my poetry embodies both the heritage of traditional Chinese culture and the innovation of Western modernism. For example, I combined the traditional Chinese concept of “harmony between humans and nature” with Western ecological ideas to develop a unique eco-poetic philosophy. My theory of “objectivist poetics” also reflects the integration of Chinese and Western poetics: it draws on Western narratological theories while incorporating the traditional Chinese idea of “viewing things through the lens of things themselves” .

In your view, what is the greatest challenge — and perhaps the greatest reward — in translating poetry compared to prose?

Translation of prose places greater emphasis on the accuracy of semantics and coherence of logic, with relatively few constraints on form. On the premise of preserving the original meaning, translators can make appropriate linguistic adjustments.

Poetry features a unique relationship between form and meaning, exhibiting characteristics of mystery and polysemy. This linguistic trait enables poetry to carry infinite connotations within a limited length.

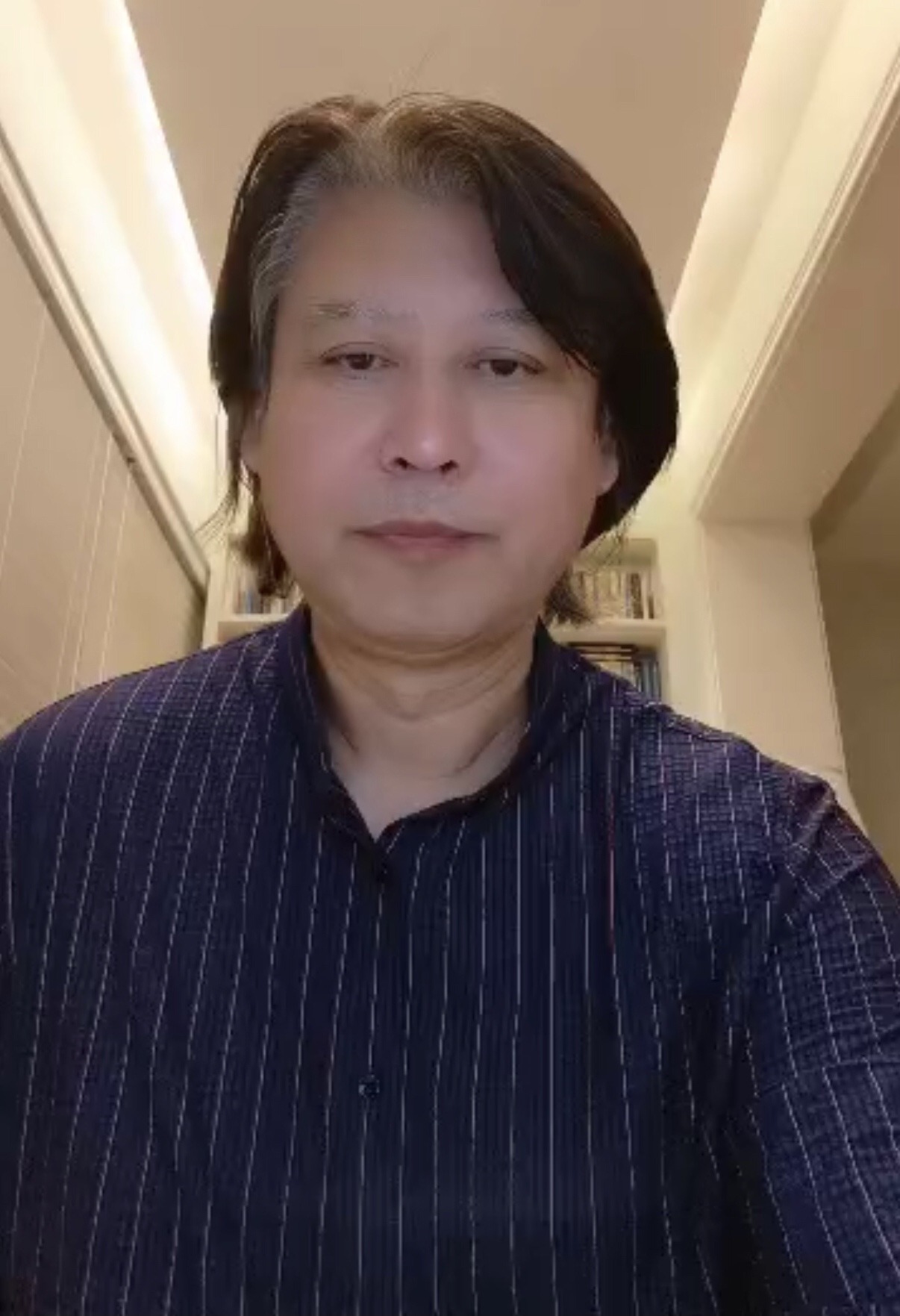

Professor Ma at Luoyang Normal University, September 2025

If poetic writing is about expressing the “inexpressible,” then translation is about “accomplishing the impossible.” The inherent differences between language systems mean that poetry is indeed untranslatable in a strict sense. It can only be a vague imitation—like “viewing flowers through a barrier”—and a re-creation of the source-language text using the target language, as well as a re-interpretation and expression of the original work’s cultural value in a new cultural context. Inevitably, this process may lead to some loss of the original poem’s cultural uniqueness, trapping the translation in the dilemma of cultural homogenisation.

No two languages share an identical phonological system, making it impossible to recreate the sound effects of a work composed in one language using another. Such phonological differences not only affect the musicality of poetry but also directly relate to the expression of its meaning, for many poetic effects are precisely achieved through the subtle arrangement of sounds.

Secondly, differences in the syntactic structures of different languages make it impossible to replicate the grammatical features of the original work. For example, personal pronouns cannot be omitted in English; however, in classical Chinese poetry, explicit subjects are often unnecessary. This difference not only impacts the surface structure of sentences but also relates to the construction of the poem’s artistic conception. The omission of subjects in classical Chinese poetry often creates an ethereal and implicit aesthetic effect—one that is difficult to directly reproduce in English.

In my view, the greatest challenge in translating poetry is not cultural differences, but rather how to convey the original work’s artistic conception and emotional depth. This is because artistic conception itself is characterised by ambiguity and polysemy; especially in poetry since the advent of modernism, ambiguity and polysemy have become the norm. Polysemy first manifests at the lexical level: the understanding of the same word may vary significantly across different cultures, and it is extremely difficult for translators to find entirely equivalent expressions in the target language. Secondly, the challenge of polysemy also lies in the uncertainty of the overall meaning. The meaning of a poem is often not single or definite, but open and interpretable in multiple ways. This openness is an important source of poetry’s charm, yet it also poses a dilemma for translation.

You have translated some of the most complex works in American literature and poetry. When you return to writing your own poems, do you find that those voices linger, or do you consciously push them away to find your own?

The impact of translation on my own poetry writing is extremely complex and subtle, so much so that I cannot clearly trace its logical thread. However, to sum it up, I quickly forget the poems I have translated. There are poets who have fascinated me for a period of time, yet my “loyalty” to their poetry is not that long-lasting. For instance, Elizabeth Bishop’s painterly observation of details once gave me a sense of “like-mindedness among kindred spirits”;John Ashbery’s deliberate ambiguity once allowed me to break free from the excessive dominance of rationality and extend toward the irrational movement of language. But it seems I have never deliberately imitated their “voices”. The influence of foreign poets on me lies more in the inspiration they provide for my poetic ideas, or in some form of spiritual encouragement.

How do you decide when a translation is “finished,” especially when poetry can feel endlessly open to refinement?

I am not a translator or writer who indulges in meticulous refinement. My own poems are rarely revised, and I approach poetry translation in much the same way: once I am satisfied that the core meaning has been conveyed accurately and the overall “atmosphere” feels sufficient, I stop revising. Moreover, after completing the first draft of a translation, I usually set it aside for a while before rereading it—treating it as a Chinese poem—to assess its overall effect in the Chinese language. The advantage of setting it aside and revising later is that you can view the translation through the lens of the target language’s conventions, gaining a detached, panoramic perspective. Only then can you more clearly observe the relationship between small details and the overall work.

If you could introduce one of your poems to a completely new audience with no context, which would you choose, and why?

I would choose poems whose images are close to life, free from comprehension barriers, and condense my core style. I am accustomed to exploring profound meanings in small daily things, extending to reflections on “existence” and “time,” and realising a leap from mundane experiences to a certain mysterious realm.

Such poems not only retain the philosophical nature of my poetry but also avoid excessive abstraction. I have selected my elegy Ode to Mother: Litany of Fire.

Through the arrangement of a series of images, it presents a breathtaking moment of final farewell—the cremation process of my mother’s body. It confronts an extremely cruel experience in life directly, while those aesthetically pleasing images fully aestheticise this cruel experience, creating a certain distance for emotional response.

Ma Yongbo, 12th June 2025, Nanjing, China, Planet Earth, The Universe

Helen Pletts, 16th July 2025, Cambridge, UK, Planet Earth, The Universe

Ma Yongbo and Helen Pletts: A Dialogue in Poems

If Ma Yongbo’s work reflects a life between languages, his collaboration with British poet Helen Pletts shows how those languages can meet in an ongoing conversation. What began online in early 2024 grew quickly into steady exchanges of drafts and translations — a conversation in verse carried across time zones.

(Helen Pletts is a Cambridge-based poet whose work is marked by a strong visual sensibility and a precision of phrasing that often draws from the natural world. Her poetry has appeared in a range of British literary journals, and her collections explore themes of identity, love, loss, and the fleeting textures of daily life. She is as attentive to the shape of a line on the page as she is to the sound of it in the ear, a quality that makes her work particularly well suited to the intimate format of poetic correspondence.)

The practice prof. Ma and Pletts share has a long history in China. Poetic correspondence (zèngdá shī 赠答诗) stretches back more than a millennium; poets such as Bai Juyi and Yuan Zhen, or Su Shi and Huang Tingjian answered each other in verse to keep in touch and discuss ideas. The exchange was both personal and public — a way of deepening bonds between poets, and at the same time creating works that could stand on their own in the larger literary record.

In prof. Ma and Pletts’s case, the tradition has taken on a cross-cultural dimension.

Writing in different languages — Ma in Chinese, Pletts in English — they translate each other’s work so that every poem exists in both languages.

Their collaboration is also part of a larger project. Their first bilingual volume Night-Shining White will be published in 2025/26 by Open Shutter Press (UK), presenting many of the poems in their original languages with facing-page translations.

For readers, this will offer the rare chance to see how a poem lives in two languages — not as an exact replica, but as a living text that adapts to each voice and cultural frame. For both poets, it is also a statement about the possibilities of literary exchange in a time when distance often feels unbridgeable.

Professor Ma, when you receive one of Helen’s poems, what is the first thing you look for before beginning your response?

To be honest, I am not as quick-witted as Helen. She can finish a short poem in just ten-odd minutes, and her inspiration is so abundant that I can’t help but feel both admiration and, at times, a touch of envy—for my own inspiration comes at a much slower pace. Helen seems to have acquired a magical ability: she can quickly transform any material into poetry while maintaining consistent quality, with rarely a flawed piece. Every time I see a poem clearly marked by Helen as written for me, I feel a sense of gratitude. Regardless of whether the content of the poem has an explicit connection to me, I always experience a feeling of joy. Naturally, my first curiosity is to find out how she sees me in the poem.

People always hope to see their own image reflected in the mirror of another, and I am no exception. What I most want to perceive is that sense of “connection”—it lets me know, amid the long years of loneliness in creation, that the world exists; especially that in another language, there is another lonely soul who exists, not only for herself but also for me. Through the unceasing translation of each other’s works and our responsive poems, Helen and I have built a space where two souls can breathe.

I haven’t had the chance to write responsive poems for many of the pieces Helen has sent me. Among the responsive poems I have completed, sometimes I make a direct response to the core theme of her poem—much like two people engaging in a dialogue around a topic. At other times, however, I start from a certain point that touches me and develop a poem that seems to have little connection to the main theme of hers. Take, for example, our responsive poems about collars and candles. This kind of “response” is a bit like two friends chatting casually by the fire: it is more free-spirited, and sometimes it can even spark new ideas and inspiration more effectively. Going off-topic can be interesting too.

How do you decide which elements of her imagery to keep in your own language, and which to transform?

I tend to retain all her images and follow them closely. My translation is guided by the principle of faithfulness, which requires the translated text to convey the meaning and ideas of the original work accurately and completely.

Beyond that, I also transplant the original images exactly as they are. The images themselves are ideas, so it is even more important to convey them in full. Images also serve as a guarantee for the polysemy of poetry; I oppose oversimplifying rich and concrete images into abstract ideas—translations that merely convey the general meaning of the original cannot be called poetry.

To date, I have translated more than 470 of Helen’s poems from different periods and in different styles, and as far as I can remember, I have never reduced or omitted any images from her poems, but remained fully faithful to the original.

The only instance where I made an adaptation in Chinese was with her poem “red residing in me at the white core of everything shiny” She used a great deal of the word “red,” and to avoid monotony, I made subtle adjustments during the translation by using different Chinese vocabulary to express the concept of “red.”

The tradition of poetic correspondence has deep roots in Chinese literature. Do you see your exchange as part of that tradition, or as something entirely new?

The responsive poems exchanged between Helen and I not only inherit the tradition of poetic exchange in Chinese poetry but also represent a brand-new attempt against a cross-cultural backdrop.

In ancient China, poets often responded to each other through poetry. For instance, Bai Juyi and Yuan Zhen produced a great number of such responsive works.

Helen and I also create both responsive poems (works that directly echo each other’s themes or images) and poems on the same topic. Traditional poetic exchange is usually infused with emotional communication and resonance between poets; in our interactions, Helen and I express our respective understandings of life, insights into emotions, and more through poetry. For example, we both experienced the grief of losing loved ones, and we comforted each other through poetry—this kind of emotional resonance and communication aligns with the essence of traditional poetic exchange.

Building on this inheritance of tradition, we have also made our own new attempts and innovations. One notable aspect is our cross-cultural backgrounds: traditional Chinese poetic exchange mainly occurred between poets within the same cultural context, whereas Helen and I come from different countries, with distinct cultural backgrounds and literary traditions. Our exchanges integrate Chinese and Western cultural elements. For example, I incorporate the imagery of yin and yang from Eastern philosophy in my poems, while Helen often creates against the backdrop of Western mythology. This cross-cultural exchange brings new elements and perspectives to poetic exchange.

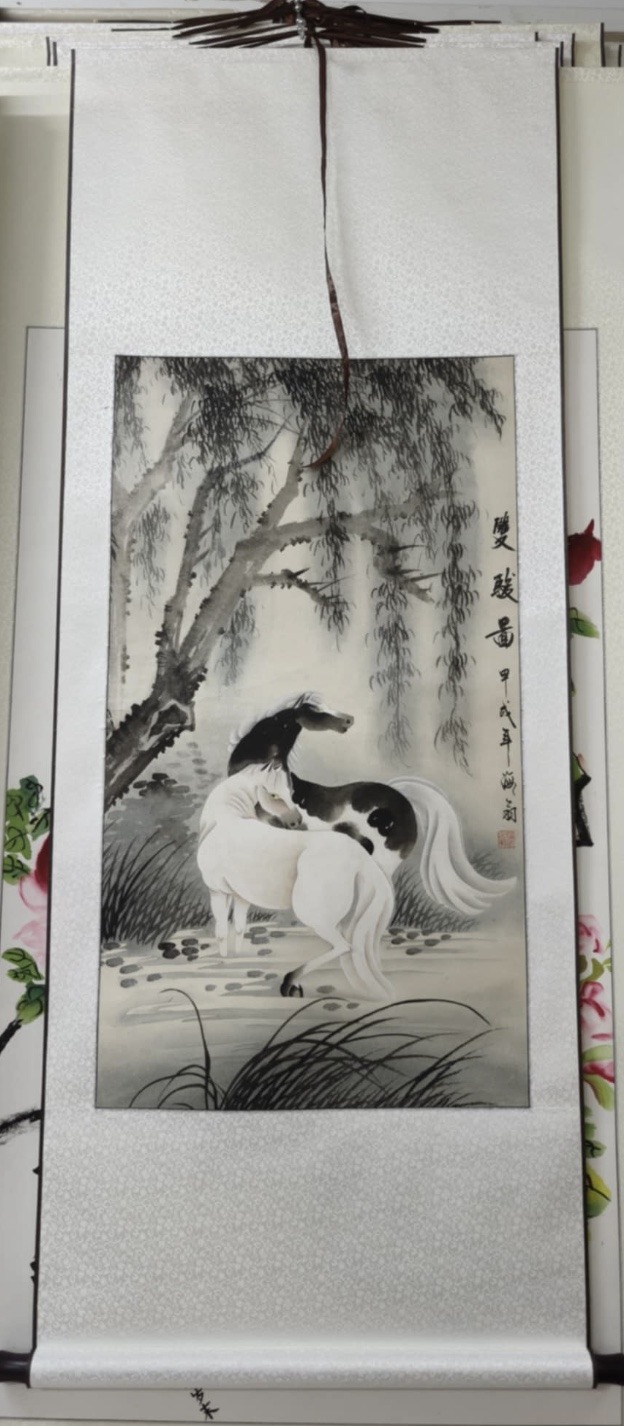

Additionally, our responsive poems incorporate modern and postmodern elements. Take the creation of works related to the painting ‘Two Horses by Hai Weng 海翁’ (a gift to Pletts from Professor Ma Yongbo on the 15th April 2025), as an example: these pieces embody the convergence of postmodernism and Zen aesthetics.

Such innovative creative techniques and concepts have injected new vitality into the tradition of poetic exchange. Helen’s poem of this series carries a passionate and spirited emotional tone, filled with praise for strength, freedom, and light, and eulogises a spiritual realm that transcends the ordinary. In contrast, my responsive poem to it adopts a tranquil and leisurely emotional tone, brimming with love for nature and life, and strives to convey a sense of inner peace and calm.

Helen’s poetic language is concise and full of tension, while my linguistic style is relatively more natural, with looser sentence structures and a gentle rhythm.

Ma Yongbo purchased the painting, ‘Two Horses’ by Hai Weng 海翁, in Harbin’s Chinese Baroque Cultural Street also known as Lao Daowai 老道外 and gifted the ‘Two Horses’ to Helen Pletts, April 2025.

two soft horses of golden sunlight—for Yongbo

together they are blazing in the bright street,

their hooves occasionally meeting in sparks.

Gold re-fashioning their soft forms;

light softly entering and re-entering their shapes.

How does a horse move silently

as a ribbon of stolen light?

What door is left ajar?

Without the dull fixings

they gently spin in softer air?

And every surface of glass shimmers,

clouds are left undefended.

They can neither grey, nor whiten;

the sun is the furnace keeper of two.

20th April 2025

两匹柔软的金色阳光之马——致永波

它们一同在明亮的街道上燃烧,

它们的蹄子偶尔碰撞出火花。

黄金重塑着它们柔软的身形;

温柔的光反复进入它们的轮廓。

一匹马如何无声地移动

像一条偷来的光带?

是什么样的门虚掩着?

没有笨重的羁绊

它们在更柔软的空气中轻轻旋转?

所有玻璃的表面都在闪烁微光,

云朵卸下防备。

它们既不变灰,也不变白;

太阳为它们两个守护着熔炉。

2025年4月20日

Freedom in Spring — For Helen

A willow uses its soft green tresses

to tickle its own reflection in the water

A silver stream listens to itself

its garbled stories will gradually grow clear

In the dark soft mud beneath the water, walking clams

reveal their chubby, fleshy bodies

Two horses, one black, one white, stand dozing by the river

swaying gently, sometimes rubbing their shiny rumps

printing wavy barcodes on everything around them

In the distance, green mountains rise and fall softly in sleep

clouds stay motionless, holding back another rain

Everything dozes lightly, as sweet as breath in the ear

April 20, 2025, midnight

春天的自在——给海伦·普莱茨

一棵柳树用柔软的绿色发丝

撩拨自己水中的倒影

一条银色小溪倾听着自己

它含混不清的故事会逐渐清晰

水底漆黑的软泥里,行走的河蚌

露出粉嘟嘟多肉的身体

两匹马,一黑一白,在河边站着打瞌睡

微微摇晃,有时摩擦着发亮的臀部

给周围的事物打上波动的条码

远处的青山在睡梦中轻轻起伏

云彩久久不动,忍住了又一场雨

一切都在浅睡,甜蜜如耳边的呼吸

2025年4月20日午夜

Helen Pletts

Helen Pletts is a Cambridge-based poet whose work is marked by a strong visual sensibility and a precision of phrasing that often draws from the natural world. Her poetry has appeared in a range of British literary journals, and her collections explore themes of identity, love, loss, and the fleeting textures of daily life. She is as

attentive to the shape of a line on the page as she is to the sound of it in the ear, a quality that makes her work particularly well suited to the intimate format of poetic correspondence.

You’ve worked with many different poets, but collaboration with Professor Ma is also a cross-language, cross-culture experience. Has it changed the way you approach your own writing in English?

I have only worked closely with other poets and artists internationally. I met graphic illustrator Romit Berger in Prague, who illustrated my poetry for over ten years from 2010. I have edited a few English translations of single poems for other poets but Professor Ma Yongbo is the only consistent poetry partnership that I have ever embarked upon and this has also developed into a very deep and meaningful friendship, where we two can say absolutely anything to each other.

The only point at which I felt less communicative was on experiencing severe illness, in case it was too distressing for Professor Ma Yongbo, or too irrelevant to our writing and translation, which is our great shared purpose.

However, Professor Ma Yongbo soon corrected this, offering his full support for any worries and concerns that I had, listening to me attentively and even researching my adjuvant treatments. Our connection is completely symbiotic. I am inspired to write because he is my first reader and the process of translating his fascinating work has enabled me to become inspired by his life too. I went around with a phrase of his in my head for days:

“I am like a child, or like God,

who carefully counts his treasures, then calms down.” Ma Yongbo (Snow falls on snow)

Helen Pletts with Sox, 1st January 2026, Cambridge, UK, Planet Earth, The Universe

From very first reading it, on the 12th February 2024. I kept thinking, ‘who writes like this?’ I was reading the first translation of his poem by Deborah Bogen.

We re-translated ‘Snow falls on snow’, together at a later date for Claire Palmer at International Times. IT.

My poetry with Professor Ma Yongbo is continuously evolving because he introduces me to his great intelligence through his own poetry in translation and it is like opening the vault to some great expanding universe of reasoning, ideas and beauty and how could anybody as curious as myself simply walk on by. Of course I have to go in and look.

His poem (Rooms in my body), an early co-translation was so unusual that it peaked my curiosity further and I was greatly relieved to hear that he had written nearly 2000 poems because I was enjoying myself so much that I did not want to run out of the possibility of new co-translations.

My own poetry style suddenly became freer, and after writing much prose poetry, I decided to skip with form entirely, concentrating on creating images that I was fast learning would magnify in Chinese and be very enjoyable to read, I did not change my thinking as a writer, I just removed all my preconceived ideas about language entirely and wrote in the moment anything and everything that I was feeling.

One such poem is ‘this is the violet hour’ which has now been translated into 8 languages, including Chinese by Professor Ma. International poets and translators have often noticed my poetry through their own direct contact with him first.

This new found confidence is a direct result of him, of not being alone as a writer and of really becoming so dependent on the other part of your partnership that you become courageously imbued with a sense of freedom and energy.

I will write anywhere and send my first draft to Professor Ma and then an overwhelming sense of peace and fulfilment, or joyousness creeps in, I am so delighted myself by what I have written because it feels natural and yet every word seems to be consciously working hard. I simply could not write like this without him.

He likens us to a Catamaran, in my birthday poem (Catamaran —A Birthday Poem For Helen Pletts) and this is indeed the perfect analogy for us, and it suits us both, we inspire each other equally and continuously and we are all the better for it.

We relax into our work together knowing there is always a welcome exchange and kindness between us both.

This support extends into everything into our lives, giving us an even greater continued feeling of support, someone always there cheering you on no matter what you do. We had both lost beloved family who used to do this for each us, within the space of one year, his brother Ma Yongping and my mother Ann Bannister.

Some poems seem to resist translation. Can you recall a moment where you found an unexpected solution for something that seemed untranslatable?

The joy of working on translation with Professor Ma is that he knows that I only want to find the best point at which his poetry connects with an English reader and this does not mean recreating his poetry in the process.

I wait to find his voice and his Avant garde poetic style creates the most beautiful imagery. At the beginning, I spent over a week on individual translations and they were more my voice than his. Lyrical and meaningful but his own poetic voice is very strong. I had to leave my voice behind and just engage my own poetic sensibility.

Semi colons and hyphens in English can have a bizarre affect in Chinese, making translation very difficult. Chinese has no capital letters, pronouns are complicated, likewise tenses.

I decided to translate in the present tense where possible to keep control of the poetic text and to create a more intimate experience for the reader.

Professor Ma Yongbo has often been criticised for being overly Western in his own poetic style. He can create poetry in Chinese but it is in a Western format, with stanzas and phrases.

I remember when he wrote a poem directly in English (Columbus’s Cat) and we were both very excited and inspired.

Professor Ma is a genius, very few can produce over 80 books—nine of his own poetry, alongside tens of translated volumes—without being gifted, while also always working simultaneously full time. He is also a recognised art critic and editor.

One poem title stumped me for days (While together they no longer). It is because grammar is awkward to match and so phrases often fall apart making little complete sense, there may only be one phrase like this per poem. It would be easier to just assume a possible sentence, not to spend hours looking for it. I have to keep looking for it.

Professor Ma Yongbo has taught me not to overwork a translation, yes, you can sometimes feel that a word is missing or not quite right, but whole phrases seem to land where they should be quite quickly and what you discover first always sounds a little beautiful but fragmented, but this is often when it is most accurate too, line lengths are irregular, Chinese Characters always look more compact than their English phrases.

One common practice of past Chinese translators, was to split an English phrase into two lines, from one line of Chinese, to create greater visual compatibility but I do not think this is necessary.

Poetry can be a solitary craft. What does it give you to work in dialogue with another poet rather than alone?

It gives you greater visibility as a poet to connect so closely, greater self-worth and in your heart and head you begin to clearly identify with writing as your most important goal. I used to put everything before writing.

Now I put writing first, apart from family emergencies, illness. I could not possibly have done this sooner as a mother. 64 is a very late age to be starting to do this so ardently.

Professor Ma Yongbo is very supportive but he also has many other projects and so any time he can spare to work with me is greatly appreciated, he is constantly occupied, in great demand internationally, but he is also my dearest best friend, whom I treasure, and I consider myself very lucky to know him.

Selected poems and information about Ma Yongbo and Helen Pletts are available on the website: www.helenpletts.com

Ma Yongbo is also the co-author of Border Conversations (with Nolcha Fox), a recent collaborative volume exploring cross-cultural poetic dialogue.

Follow Professor Ma on Instagram @mayongbopoetry

Follow Helen Pletts on Instagram @helen.pletts

Taken together, the exchange between Ma Yongbo and Helen Pletts shows that poetic correspondence is not a relic of literary history, but a practice that continues to adapt to new conditions.

Their poems and reflections move between languages and personal experience, without smoothing over difference or pushing toward agreement. The value of the exchange lies in its continuity: in the sustained attention each brings to the other’s work, and in the patience required to write, translate, and respond across distance.

Read alongside their reflections, the poems reveal how dialogue is built not through consensus, but through repeated acts of listening and reply. In this way, their correspondence points to a simple fact — poetry still offers a space where thinking can happen in company, over time.

Ivana Milanovic, Editor-in-Chief, Jade Moon, Issue 3, February 2026

All images under individual copyright © to either Ma Yongbo 马永波 or Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨 or Ivana Milanovic

.