Powell & Pressburger’s elegiac 1944 film

If we are lucky, an intense appreciation of our own moments and memories may lead us to timelessness. Place also, can equally be transcended through fully realising those particular places we love most. In similar fashion, at certain moments, A Canterbury Tale, surpasses the medium of film altogether. That a story partly tailored as wartime propaganda and set in Kent in 1944 can incorporate such a sense of universal timelessness is something of a miracle. But how many of us, 75 years later, can remain open to this miracle? Like some ancient forerunner to the so-called ‘slow’ cinema of Tarkovsky and others, the contemplative sections of A Canterbury Tale decelerate into something special, something extraordinary, something beyond description. But who still notices this? Who still wants it? To the mainstream viewer adapted to the frantic, kinetic pace of modern cinema and television, all such thoughtful films will appear frustratingly languid . . . and once you reverse back more than 70 years into the realms of A Canterbury Tale’s black and white, some of the jokes and attitudes are bound to seem politically incorrect, while much of the acting is likely to appear wooden[i].

Accustomed to our diet of adrenalin, excess and excitement, how many of us can manage to achieve the space to look inside or backwards? For it’s not just in our escapism that we crave choice and excitement. In every aspect of life, most of us have grown used to thriving on a shallow rationalistic surface, addicted to a lifestyle that is dangerously or terminally unsustainable. Yet what political party in all the years since the Second World War would have dared to suggest, that excepting those at the harsher end of society, we should all be prepared to lower our standards of living, or that we should have retained some of the virtues of rationing? Only now, with hindsight, are some of us coming to realise how we should have been living for the last fifty years. For aided and abetted by the hopeless flightiness of our media, (perpetually transfixed by the latest trivia), our hyped-up surface has also been blocking out the future. We’ve known for decades that the dead-end was coming and we just haven’t done enough. To quote Professor Jem Bendell’s opening speech to Extinction Rebellion members gathered at Oxford Circus in London this week: “most of us have been too afraid to look closely at what is happening in our world . . .” https://jembendell.wordpress.com/

So, before the inevitable power cuts and food shortages come, (and I would accept having power only 3 days a week – as we all should – if it would make enough difference) take another look at Powell and Pressburger’s under-appreciated pastoral. It’s been my favourite film since 1984, just ahead of Tarkovsky’s Solaris. You may need to have patience at first, to keep calm and carry on, but if you watch and listen carefully, you may receive its transmission of secrets – its evocation, not only of timelessness, but also of the comparative safely and stability (and I’m really not joking), of the Second World War:

A Canterbury Tale – as reviewed for Moviemail in 1996

After the notorious reception that greeted Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom in 1960 – one reviewer asserting it should be flushed down the nearest sewer – Powell’s storm-tossed reputation seemed finally wrecked. For the rest of his life Powell (1905-1990), though valued by younger filmmakers, notably Martin Scorsese, struggled to get major film projects off the ground. But films as distinctive and once celebrated as Powell and Pressburger’s couldn’t stay obscure for long; their colours are just too vivid! By the time the British Film Institute’s drew up a list of 360 world film classics in the 1990s, Powell was represented by six and a third films (a third for 1940’s The Thief of Bagdad), including Peeping Tom. Unfortunately, perhaps because of its comparative black and white subtlety, A Canterbury Tale is not one of them.

In England, Powell and Pressburger were always regarded with a degree of suspicion. They were too brash, too Romantic, too European. When their reputation was reborn in the 1980s it’s not surprising that their most valued films would be those most obviously, colourfully, brilliant. By contrast, A Canterbury Tale is a quiet, mystically tranquil symphony to the land, a rural accompaniment to the predominately urban film songs of Humphrey Jennings.

The plot may sound absurd, hinging as it does on the unmasking of the enigmatic `Glueman’, but it is the depth of the film that counts. In A Canterbury Tale, depth is as far in the foreground as it’s ever likely to be in what is a very accessible film. It’s not, as has often been said, a reactionary retreat to nature or a nostalgic withdrawal into the past. Nature and rural crafts are clearly celebrated, but as historical facts, as the depth of where we come from. Time and memory and tradition are the indicators and gateway to a sense of timelessness. Personal associations of depth, such as in the lecture given by Colpeper, the messianic magistrate astonishingly lived by Eric Portman, “isn’t the house you were born in, the most interesting house in the world for you?”, are likewise the gateways to a common universal depth. Far from being reactionary, it is actually the most traditionalist aspects of certain characters in A Canterbury Tale that are gently condemned. Colpeper’s deepest instincts may be sincere, but at a social level, his familiarity with the villagers he unconsciously considers his subjects, and the soldiers he wishes to convert, isn’t real enough to prevent his aloofness from isolating him. Only when he begins to love personally, does he have a chance to emerge from the harvest evening of his own making.

On our meandering journey, flowing as a slow river through the landscape, there is talk of medieval pilgrims, and of the traditions that unite U.S. soldier Bob Johnson with his English forbears. There are many stories and surfaces: the celebration of England past and present serves as war propaganda leavened with many authentic comic contrasts between yank and limey. There is a retrospective love story (beautifully conveyed by Sheila Sim) and the gradual enlightenment of Colpeper, as well as a brief tale of cynical adaptation to artistic disillusionment in the modern world. All these strands are resolved at the end: the modern-day pilgrims receive their blessings or as penance, must return to twilit isolation. But the real story is in the depth. The real `story’ is in the view of the vale looking across breezy sunny trees to the cathedral; is in the woods, grasses and clouds, and how all these are envisioned in the minds of the characters. Their wishes and dreams become ours.

All our most valuable art works in ways such as this – by their quality of depth being able to chime with our own depth, our own personal memories and hopes. It is never escapism – quite the contrary: It is our normal daily way of life, of existing without sufficient attention to depth, that is the escape. In the escapist reality of modern society, dependant on apparent precise explanations, it isn’t surprising that depth is undervalued or overlooked, or in the case of Powell and Pressburger’s films, that the bolder Technicolor fantasies take precedence over A Canterbury Tale’s ambience of unassuming depth.

Despite being resistant to clear understanding, the depth that figures so powerfully in A Canterbury Tale, remains always present in life for anyone open enough to feel it, and not be over distracted by surfaces, or by beginning, middle, and end.

Lawrence Freiesleben 1996 and April 2019

[i] From my digression: Things Behind the Sun – A Digression on Memory, Trauma and Mystery. February 2018: The scene in A Canterbury Tale (1944) when Sheila Sim locates the old caravan in which she spent a summer with her now missing airman fiancée, remains unbearably moving to me: her crumbling face, the music, the whole atmosphere . . . But many – even those used to ‘old’ films – find the scene wooden, pleading, dated unto absurdity.

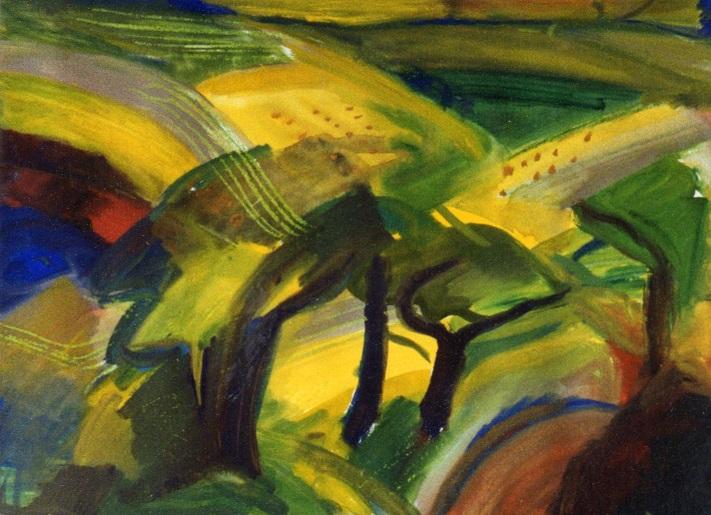

Title painting: Heart of Oak Cross Gouache & Oil Pastel 55 x 76 1988

[…] [i] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMJ8lVXXNP8 (sourced 18th February 2018) From approximately 1hr 47.19mins. To those who don’t find this scene powerful I would suggest you’re not making enough effort – or haven’t relaxed far enough into the well of universal emotion! Originally seen in 1984 and still my favourite film: see http://internationaltimes.it/a-canterbury-tale/ […]

Pingback by Things Behind the Sun – A Digression on Memory, Trauma and Mystery | IT on 13 July, 2019 at 7:20 am