I first became aware of Ken and Elaine Edwards around 15 years ago in what was at that time my local pub – the Jenny Lind in Hastings Old Town. They were playing in their band the Moors. I was struck immediately that here was fusion music – an eclectic mix of rock, jazz, spoken word, poetry and improv, inflected with musical influences from North Africa – that actually worked; it sounded like its own thing, rather than a mash-up of styles and influences that didn’t quite belong together.

I used to hear Elaine working on her scales on the saxophone as I passed their house: they lived in the next street. As the years went by, the Moors morphed into Afrit Nebula, a three-piece band featuring percussionist Jamie Harris, who came recommended by veteran British jazz luminary Trevor Watts. Later, when Harris rejoined Watts’ band, he was replaced by drummer and percussionist Yair Katz.

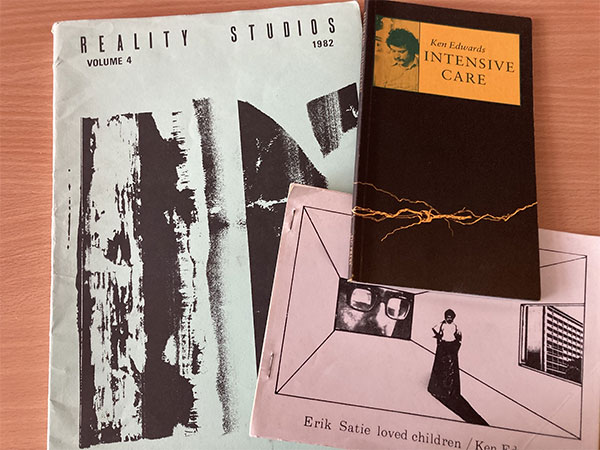

Late last year Ken gave me his book Wild Metrics: as well as being the bass player in both the Moors and Afrit Nebula, Ken is an author, publisher, poet and spoken word artist. The book was set mainly in London in the 1970s, and captured perfectly the alternative arts scene of its day – poets reciting in pubs and dingy clubs, the happenings, the arts labs, the licensed squats, the drifters, losers and loners and people sadly adrift in life – and the mimeographed literary booklets. These would often be run off on the Roneo or Gestetner machine (too involved to explain here – look it up!) that someone who worked in an office had down-time access to. These were effectively home-crafted zines in their early incarnations, before the arrival of photocopiers. They would be sold or given away or exchanged for a pint and a roll-up in those same pubs and clubs, hawked on the streets, or distributed through alternative networks via the postal service.

At the same time that I was given Wild Metrics, I also bought a copy of Inalienable by Afrit Nebula, and Elaine’s The Bulverhythe Variations – something like a lockdown diary in book and CD form. Bulverhythe is a stretch of beach in St Leonards that is home to the wreck of the Amsterdam, a remarkably intact, 260-year-old Dutch East Indiaman cargo ship, once the property of the now-notorious East India Trading Company. It now lies submerged in the soft silty sand, and is fully visible only at very low tides. Dominating the landscape is a former railway diesel shed, now a repair workshop for ageing locomotives and carriages.

Intrigued by all this, I visited Elaine and Ken in their seaside home in Hastings to learn more.

KR: 1. Can you tell us about the events described in Wild Metrics, and how in broad terms you got from there to making music? Did your experiences in the alternative culture of the 1970s inform your work as a musician? If so, how?

Ken: Wild Metrics is an account of four years in my life (1974-78) when I was heavily involved with the licensed squatting and avant-poetry movements in London. It’s based on the diaries I kept at the time, and was originally going to be a novel, but it didn’t work as fiction. I tried changing everybody’s name and embellishing the narrative but somehow that just killed it. So I ended up writing it as a memoir (with some names changed). I appended a disclaimer: “This is essentially a work of imagination. Names, characters and places have a complex relation to real people and locations, and incidents narrated may not necessarily have occurred in the way or in the sequence described, or at all. Apologies for any confusion created.”

Although I had taught myself to play a few chords on guitar and was passionately interested in music, I was not an active musician at that time. I was writing songs, but was mostly too shy and lacking in confidence to perform them in public. Even doing poetry readings was a nerve-shattering experience for me. It’s different now, I love performing. I knew a lot of poets, including the sound poet Bob Cobbing, and people like Jeff Nuttall, Barry MacSweeney, Tom Raworth, Lee Harwood, all of whom are now dead. (I didn’t cross paths with Pete Brown, the Cream/Jack Bruce lyricist, but had his books as well as the albums, and met him briefly many years later in Hastings, my current home town, where he had come to live. He died a few weeks ago.)

It was an exciting time, we felt we were overturning all the dead norms of writing. It was at that period that I also started publishing, at first using a Roneo duplicator (mimeograph machine), which will be a complete mystery to young people today. Even in the time before digital culture and the internet we could make our own books!

The central part of Wild Metrics is an account of being hired to work for a very famous musician. It was a bizarre three months in my life: one day I was living in a condemned house in Bayswater, west London, the next I woke up in a palatial ensuite room in the St Regis Hotel in New York. I anonymised him in the book, but it doesn’t take a lot of detective work to find out the musician was Paul McCartney. I have been asked why I called him “The Rock Star” throughout, and changed the names of his band (Wings), family and entourage. Was it because I was afraid of being sued? Not at all, there’s nothing libellous in the book. I just didn’t want my memoir to be overshadowed by such a ridiculously famous being. I was actually hired as a private tutor to 13-year-old Heather, Paul’s stepdaughter (daughter of Linda). The family was embarking on a three-month tour, Wings Over America, and Heather’s school had stipulated that they must take a tutor so that she would not miss out on schooling. It was by turns a frustrating and fascinating experience. I did get to hang out a bit with Wings (Denny Laine and Jimmy McCulloch were lovely guys) but mostly I spent time mooching about in hotels and occasionally being taken to wherever the McCartney family were staying so I could give Heather her lesson. As a result, I got an up-close view of what extreme fame is like. It is not nice. The one musical lesson I took from it was the value of intense preparation: Wings were fantastic on stage throughout (from my conversations with Paul it was obvious he was trying to recreate the energy of the early Beatles, which he mourned – but the Beatles were the elephant in the room, not to be actually alluded to!). He had drilled the band through weeks of daily rehearsals even before the first gig. That’s how you get good.

In the years following, I continued to write and publish, though earning my living through journalism rather than creative work. I was on the fringes of various musical projects. I had started getting more interested in jazz and various ethnic musics. In the 1990s I learned to play violin, which I can still do, though not very well, and to read music (likewise). I was involved in the East London Late Starters Orchestra and CoMA (Contemporary Music for All) which aimed to open up contemporary composition to people of all abilities and levels of experience. At a summer school in Yorkshire in 1997 I met Elaine, and we hit it off both musically and personally. We became a duo, performing our own experimental words-and-music combinations, in venues such as pub upper rooms in London and at poetry festivals.

- How did the Moors develop? Where did the North African influence come from? How do you feel the music of Afrit Nebula differs from, or expands upon, that of the Moors?

By the turn of the century Elaine had moved into my south London flat and we had a happy five years there, but in 2004 we decided to move to the coast, where we could afford a bigger house, and ended up in Hastings Old Town. Elaine had a formal music/related arts education and had achieved diploma standard on flute, but she was now learning the soprano sax and getting into jazz. We briefly had a duo playing klezmer (the music of Eastern European Jews – though neither of us is Jewish) on flute and guitar. She was frustrated that although she was depping in various jazz/swing bands in Hastings she hadn’t got a regular gig. I told her that if she wanted we could form our own band and I would play bass. I acquired a bass guitar and started learning. I soon realised I had at last found my own instrument. We got together with guitarist Richard Butler, an Old Town neighbour, and Jenny Benwell, a violinist Elaine met through teaching with the East Sussex Music Service, and started jamming, at first on the klezmer and Sephardic tunes we knew, joined later by local drummer Andy Maby. Before we knew it, we had a band: The Moors. The then manager of the Stag (a folk pub) asked us to play weekly in their back bar and people started turning up. Soon we had a regular gig at the Jenny Lind, which is probably the premier music venue in Hastings Old Town. The band members, to our astonishment, turned up every week for rehearsals at our house, whether or not we had a gig, and so we got good. We rocked! Elaine and I were overwhelmed – although we’d had a great deal of musical experience over the years, neither of us had actually run a band before.

I was brought up in Gibraltar and perhaps as a result am very interested in the traditional musics of the southern Mediterranean. The more I study the more I realise there is one music, many traditions, carried in some cases by the Jewish and Gypsy diasporas. You can hear the same scales and rhythms in klezmer, in Sephardic Jewish music, in Turkish and Middle Eastern music, in the Balkans. In The Moors we tried to fuse that with our own rock traditions, and our own compositions.

- Was the new approach as heard in Afrit deliberate or did come entirely by chance, or neither/both?

It wasn’t by chance. The Moors had become very successful locally in Hastings, Rye, Brighton and on one occasion as far afield as Brecon in Wales. But both Elaine and I were looking for a more improvisatory approach. We wanted to develop our jazz skills, if you like. The other members of the band were less keen. So the two of us decided to start a second band with this in mind. The saxophonist Trevor Watts, a Hastings resident, recommended that we get in touch with the percussionist Jamie Harris, whom he’d worked with as a duo in the past. Jamie, Elaine and I started jamming. The result was the trio Afrit Nebula. Because of Jamie’s influence, we were going further into the Afro-Cuban feel which had come into The Moors a little bit, and also some North African influence. The three of us shared an interest in jazz/improv, and we even did a cover of Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman”. Some of the Balkan influence remained. Essentially it was a more improvisatory, rhythm-based approach. We tried to keep the two bands going simultaneously, but eventually it was agreed that The Moors had done all it was going to do. We had ten good years with that band.

We played with Jamie for seven years in all, recording an album and an EP. Through Jamie’s contacts, we played at a small rock festival in the Czech Republic. We provided the music for a multi-media event at the Kino-Teatr in St Leonards with Japanese dancer Yumino Seki and film-maker Mark French. Eventually that phase came to an end when Jamie was asked by Trevor Watts to join a new trio, Eternal Triangle, which meant committing to touring. It was sad to see him go, but we had an immediate replacement in the drummer Yair Katz, whom we’d known for some time. Yair was born in Israel and spent many years in New Zealand playing in rock bands before coming to live in St Leonards. We share many musical tastes, and he gives the band a more swing-like feel. We lost Jamie’s powerful blues voice, but Yair can sing and also play guitar, so there were other options. We have recorded an album with Yair, and have plans to join forces again with Yumino Seki in a dance performance, with music mostly written by Elaine.

- Hastings is considered by many to be the Mecca of music on the South Eastern coast. How would you respond to this?

I think I can say that were it not for moving to Hastings Old Town in 2004 (we have since moved a mile or two west to St Leonards) Elaine and I would probably not have started a band. The musical culture here is vibrant. A lot of it is rock, blues and folk music, but we have tried to provide something a little different. Playing at the Jenny Lind in the Old Town is still such a buzz – we always attract a knowledgeable and enthusiastic audience. And currently St Leonards seems to be going through an art/music renaissance which we are very happy to be part of.

- As an author, publisher and musician, where do you feel your overarching loyalties lie – if they do? Or is it all subject to a continuum?

I have always regarded myself as a writer primarily, but it has been a privilege to develop my musical skills with such wonderful and talented people. The thing about writing is that it can be a lonely business. The joy of music rests partly in how it can exist in interaction with others. And I do feel that my musical experiences feed back into my writing all the time, in terms of a feeling for rhythm, pacing, sound, texture. So it’s all one really!

KR: Can you tell us about your early life and how you came to be a musician and composer.

I was born in a Norfolk village and have a typical rural working class background. Roaming the countryside on bikes and general ‘tomboy’ activities were what I liked best.

My first memory of playing piano was my father teaching me ‘Chopsticks’, closely followed by playing songs I had been learning at school. My father played the clarinet in a local dance band, and also played the accordion – sometimes entertaining people in the pub next door. I grew up hearing 1940’s dance band music and classical piano music (my older brother was a brilliant pianist). I loved it all… Very soon I like my brother began having lessons with the local piano teacher, taking my grades, performing in local functions. We also had a Yamaha electric organ and I loved to play Latin and Swing.

I left school with very little in the way of academic qualifications. In my mid twenties and living in London I hired a flute. This put me on the musical and creative journey I’m still on. Outside of my job as a medical secretary I learned how to play the flute using all my spare time and annual holidays. I had a wonderful Irish flute teacher, adept in classical, jazz and Irish folk music who I visited once a week. He believed in a kind of ‘Baptism of Fire’ approach – playing Bach flute duets for lessons well over an hour a week and sometimes music by Miles Davis. I survived and learned quickly, eventually giving up my job, moving back to Norfolk and working on piano, flute and theory in a small hut in my parent’s garden! I was following a very powerfully felt intuition during this time but actually had no idea where I was going. I was encouraged by a local music teacher to apply to college. After many rejections from universities I managed to be accepted on to a very original performance art degree in Chichester. It was a true garden of discovery – studying as a musician while relating music as a creative art form to dance, art, creative writing. Here I discovered a kind of intuitive flair for creating music and improvising – nurtured to create as we all were in this very eclectic environment.

I did a PGCE at Sussex University and taught in secondary schools – teaching music and performing arts. I organised a ‘Composers Extra Curricular Group’ for the GCSE and A Level groups – which was rewarding. I was lucky to teach at a time when adequate funding was made available to the Arts Departments in Schools (which is probably not now the case). I remember inviting composers of new music such as Stephen Montague who wrote Dark Sun (a piece about Hiroshima) to work and perform it in concert. Also African and Indian dancers, musicians and writers to work with the students. New and creative ways of working in the Arts – I felt privileged to have contributed to this.

I met Ken during this period on a Summer School for contemporary music making in Yorkshire (COMA), went on to live in Peckham, South London and eventually moved to Hastings. I was inspired by Ken’s writing and attending his poetry evenings in London pubs. Sometimes we performed together using Ken’s words and my flute compositions. I began work with what was then East Sussex Music Service working as a peripatetic teacher. I had to work very hard to retrieve my former playing skills on flute and piano to pass the auditions. My energies up to then had been going into classroom teaching and running music departments. It was also during this time I took up the saxophones (tenor and soprano) and became very interested in jazz. At the same time Ken had taken up the bass guitar, and together we formed The Moors and Afrit Nebula, which Ken has described.

In recent years I have dedicated more time to composing, improvising and collaborating on projects. I was fortunate to have piano lessons with John Tilbury at Goldsmiths College – one of the foremost interpreters of Morton Feldman’s music, and a member of the free improvisation group AMM. He introduced me to composers piano works which I think are still highly influential on my own compositions now: – works by Olivier Messiaen, John Cage, Arvo Part, Morton Feldman, Frederic Mompou, Howard Skempton to name but a few. I particularly felt this influence in my last project which was written for piano during the pandemic on a series of photos taken on my runs in Bulverhythe, St. Leonards on Sea, ‘Bulverhythe Variations’, which also combined with a narrative by Ken and was performed last Autumn at The Beacon in Hastings.

Both Ken and I have used our composing ideas in The Moors and in Afrit Nebula particularly as starting points to improvised pieces. We have been thrilled to work with some very creative and talented people over the years both in our bands and in collaborations with other art forms. We will be working for the second time with the Butoh dancer Yumino Seki in a Coastal Currents project in Hastings in September which we are very excited about.

To conclude I would like to share a quote by the dancer Martha Graham which I have often referred to for motivation. We all have an individual voice whatever our art – and I have found this to be wonderful message for the young just starting out, and the older of us who need reminding sometimes!

“There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and will be lost.”

― Martha Graham

http://www.realitystreet.co.uk/

https://afritnebula.bandcamp.com/

https://jazzjournal.co.uk/2022/08/26/afrit-nebula-inalienable/

Keith Rodway