By Jay Jeff Jones

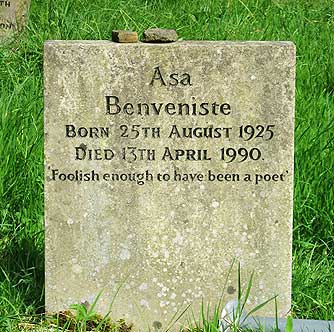

‘Foolish enough to have been a poet’ is a headstone inscription that sometimes catches the eyes of visitors to the graveyard of St Thomas the Apostle in Heptonstall village in West Yorkshire. The name of the man buried there, ‘Asa Benveniste’, also has an unusual ring. The surname indicates a Sephardic Jewish ethnicity and is more commonly seen in Spain or France . It means “You have arrived well” and the Benveniste who ended up here first arrived in the world 3300 miles away – in 1925 – in the Bronx borough of New York City.

After serving with the US Army in Europe during WWII, Benveniste decided to stay on in Paris, among hundreds of American expatriates, many of whom wanted to become writers or, for a while, to live like they were. A few, that had the money, started little magazines. Along with George Solomos, he put together the first two issues of Zero, a quarterly that attracted contributions from Samuel Beckett, James Baldwin and Paul Bowles.

He then moved on, to England, and began to develop his own poetic practices, working with the I Ching, the Tarot and other arcane sources. After finding a base in London, he settled into a lifestyle of decadent austerity – living on whiskey, wine, strong American cigarettes, black coffee, and the occasional pizza.[i]

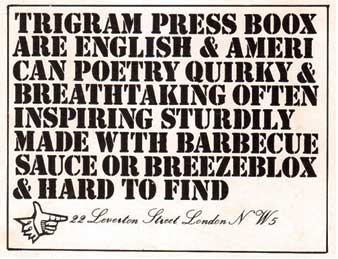

With his Cornish wife Pip, an artist and designer, Asa founded the Trigram Press in 1965, the same year that the International Poetry Incarnation was held at the Albert Hall. The initial purpose of the Incarnation was to showcase Allen Ginsberg in the largest performance space in London. Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti happened to be around so the event developed into an intersection of American and British Beat, Black Mountain College and post-Beat Underground poetry (with a few hip Europeans and a Cuban included for good measure). An audience of about 7000 turned up for an exuberant stoned word-rave, which may have gone off organisationally half-cocked but succeeded in rousing the spirits of England’s tentative alternative society.

Iain Sinclair’s later appraisal of the event noted that what the audience came for were simplistic poetic ‘formulations’ like those from Adrian Mitchell rather than the visionary ravings of Harry Fainlight. ‘What they wanted, as ever, was a protest prom, Poetry as CND sloganeering.’[ii]

Much of the material for Trigram’s publications would arrive through the transatlantic poets’ network, producing collections by Piero Heliczer, Tom Raworth, Anselm Hollo, David Meltzer, and Jonathan Williams. Asa would have hated for Trigram’s books to be judged simply on appearances, but between him, Pip and his stepson Paul, the publications were aesthetically beautiful – ‘audacious, elegant and legible’ – in the words of Jeff Nuttall, one of Asa’s friends and another poet that he published. You could say the content had a lot to live up to and vice versa, and it partly did so through Asa’s choice of artists and writers who worked in what he called ‘acute conditions of exile, living and thinking on the edge of society.’

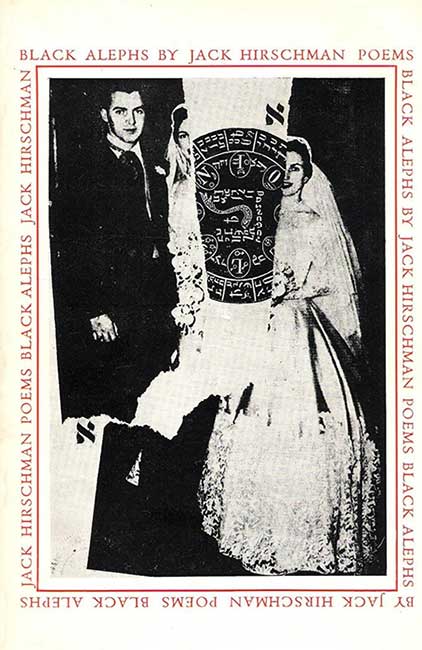

Jack Hirschman, an old friend from Benveniste’s Bronx childhood, caught up with him in London, where they discovered a mutual interest in a poetry involving esoteric investigation and divination. Hirschman described Asa’s technique as ‘Bop Kabbala’, borrowing a term from Ginsberg.[iii]

Benveniste later said that the ten years he spent engaged in studies of ‘Kabbalistic congruities’ was a dark period in his life and as a corrective, he moved on to poetry that relished the ‘silliness’ of domestic life – and in this he had uncovered a ‘complex comedy of language.’[iv]

In Benveniste’s presence, you could sense his edgy intensity about words and their disposition. Michael Schmidt, publisher of the international poetry imprint Carcanet, described him as frightening to be around. But there was an undeniably sensitive side, one that came out in the company of old friends. Once, after a long afternoon of wine and jazz, when recollecting the writer B.S. Johnson, he began to weep. Johnson had committed suicide in 1973, aged 40, partly because of what he regarded as an insufficient appreciation of his literary genius. Trigram had published a collection of his poetry and, for the only time, a novel, House Mother Normal.

After his death, Johnson developed something of a cult following – readers who have proved to be almost as devoted as Sylvia Plath’s but with only a fraction of the numbers. His poetry is less well regarded than his often confessional novels and self-interrogating short films. Even so, he was the Transatlantic Review ‘s poetry editor and a critic for Ambit. On the publication of Ariel, Plath’s first posthumous collection, he was entranced, sensing levels that would take years to fully understand. In fact, he appears to have been confounded by many of the poems, out of his depth, and declared that any review that he or anyone else wrote would be ‘irrelevant, unimportant and useless: the book simply is.’ There were some poems he found ‘overwhelmingly moving’ but regarded them, too simply, as the results of Plath’s ‘disastrous personal crisis’.[v] The tragic immortality that Plath achieved, post-Ariel, may have crossed his mind that day as he sat in his bath with a razor and a bottle of brandy.

Trigram became one of the crucial publishers of the British Poetry Revival, an establishment-shaking movement that first stirred around 1960 and perhaps ended in 1977. Largely ‘conducted’ by the critic, poet and professor Eric Mottram, the Revival could be crudely said to have encouraged poets to take risks and defy conventions. Slightly less crudely, it was a making of poems that listened to themselves rather than duplicating the received forms and tones of how poetry was supposed to be. We’ll never know what Plath might have thought of it, but Hughes was sometimes happy to mingle in the Revival’s rough little magazines.

Al Alvarez, who was the influential poetry editor of The Observer for 10 years, was unimpressed. He had launched his own revision of the British poetry agenda in 1962 with the Penguin anthology The New Poetry, where Hughes featured as a leading light. Because of their influence on his chosen native poets, Alvarez bent the rules to allow in two Americans, Robert Lowell and John Berryman. They played to his idea that the impersonality and ‘gentility’ that prevailed in English poetry was holding it back; that there could be a direct connection between the poet’s life experience (‘sometimes on the edge of disintegration and breakdown’) and the poet’s work. In the 1964 second edition, he shrewdly included Plath and Ann Sexton.

The New Poetry was a studied approach to upgrading The Movement, an exclusively English faction of poets from the 1950s that opposed the ‘excesses’ of American-style Modernism, including its ambiguity, showy word-play, and metaphysics – particularly as they saw it practiced by the ‘pretentious’ Dylan Thomas.

Interviewed in 1962, Plath had cited Thomas as one of the poets she most admired, along with William Butler Yeats and, increasingly, William Blake. Contemporary English poetry she found to be in a ‘straitjacket’ and supported Alvarez’s complaint about the inhibitions of ‘gentility’. The poet peers who excited her most were American, such as Sexton and Lowell, especially his ‘intense breakthrough into very serious, very personal, emotional experience, which I feel has been partly taboo.’[vi]

Taboo and excess were what the British Poetry Revival thrived on and was, from its origins, willingly American infected. It revelled in academic disapproval, was adept at self-publishing and circulation, welcomed a spectrum of regional and socially diverse voices, and was unrestrained in subject or form. It was also (somewhat) more open to female poets than the preceding literary movements, groups or coteries. For Alvarez it was a continuation of the Beat Generation, whom he scorned for the drugs and cult of personality (Ginsberg) – ‘…instead of using their art to redeem the mess they had made of their lives…served the mess up uncooked and called it poetry.”[vii]

‘Howls of protest heard from the shires at this unwanted double influx of domestic experimentalists and Americans,’ was how Ken Edwards, one of the Revival’s leading voices, explained the outcome of what came to be called The Poetry Wars. The Arts Council of Great Britain cleared the rabble out of the Poetry Society and took back control (from Mottram) of The Poetry Review, the Society’s magazine. Mainstream presses and the academies were reconfirmed as gatekeepers between the big top and the avant-garde sideshow, with its mountebanks and freaks. A number of Arts Council grants were withdrawn, including Trigram’s, and Benveniste began to spend more days at his typewriter.[viii]

The first time he came to Heptonstall was in the early 1980s having been invited by the Arvon Foundation to lead a residential course at Lumb Bank. The surrounding area was no longer the ghost vale once pictured by Ted Hughes. Its regeneration followed an influx of artists, writers, academics and creative staffers from regional television companies, attracted by low-cost but characterful housing. Migrants also included a Hippy diaspora more interested in the vacant, easily squatted, no-cost housing. The resulting countercultural, artistic mix was the foundation of a café life, antiques & retro, craft-making, organic / artisan food, Lesbian / Gay business community that slowly boho-charmed the rundown town of Hebden Bridge into a visitor destination.

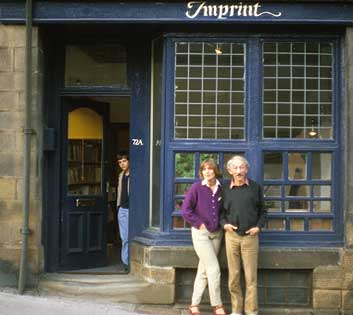

With his new partner, Agneta Falk, Benveniste found a house in Hebden, set up the ground floor as a bookshop and mostly stocked it from his own library. The Poltroon Press publisher Alistair Johnston came to Heptonstall in 1982 – pursuing a project to collect selfies at famous poets’ graves. For fun he also photographed Asa, crouching behind Plath’s headstone like a Kilroy-was-here imp.[ix] This clowning was purely for the camera, not a mockery of her work or its advancement into the canon – not even a jest in the direction of Plath’s attendant faithful. And only eight years later, he was buried in a plot only a few paces away.

The elegies that followed his death, on 13 April 1990, included one by Roy Fisher[x], a poem that concludes with a jazzy eye-witness report of the cortege of outsider poets, artists and actors who attended Heptonstall Church for a celebratory performance – and then the bacchanalian wake with ‘barrelhouse music’, and where the clocks were not the only things that became seriously ‘unhitched’.

In contrast, Plath’s funeral had been short and sombre. A small service in a Hebden Bridge undertaker’s chapel was followed by another in Heptonstall Church. In attendance were Hughes, his father, a few family members, and two friends from London. From Plath’s side came only her brother Warren and his wife.

The most basic death notices had appeared in the London press, with the pointed exception of “A Poet’s Epitaph” by Alvarez in the Observer. Alongside three of Plath’s most recently completed poems he described the state of mind that had produced them, suggesting that this had drawn her to a certain fate. Whilst writing ‘almost as if possessed’ she had concentrated on, what he believed, was a ‘narrow violent area, between the viable and the impossible, between experience which can be transmuted into poetry and that which is overwhelming.’

Four months earlier, in an interview for the BBC, Plath had also discussed ‘experience’ being the subject of her latest poems, but as something she felt confident and happy about. Even if drawn from highly ‘sensuous and emotional experiences’ she expected to control the ‘most terrific’ ones, even ‘madness’ or ‘being tortured’, and be able to ‘manipulate these experiences with an informed and an intelligent mind…’.[xi]

As far-flung as Heptonstall then seemed from the contemporary world, once Ariel had been published, it didn’t take long for her burial site to attract visitors. After almost 60 years, thousands (from every part of the world) have been, some of them making repeat trips. With a modest published output (four slim poetry collections, one novel, collected stories, and journals – later added to with ‘Selected’ and ‘Collected’ editions, diary pages and letters she might rather have kept to herself)[xii] Plath eventually became what waggish publishers’ accountants call ‘an industry’. The bulk of material has come from others – multiple biographies, documentaries, a biopic, essays, enough theses to choke a library, conferences, seminars, festivals, encyclopaedia entries and other devotions. And, to her mother’s displeasure, her grave not only came to be treated as a shrine, but one that more obsessive devotees thought they were entitled to an opinion about.[xiii]

Regarding the confiscation of Plath’s life and work, her daughter Frieda made herself clear in the poem “Readers”. ‘While their mothers lay in quiet graves / Squared out by those green cut pebbles / And flowers in a jam jar, they dug mine up.’ And then, ‘They scooped out her eyes to see how she saw, / And bit away her tongue in tiny mouthfuls / To speak with her voice.’[xiv] With more detachment, the poetry critic Christina Patterson called, ‘The sanctification and widespread appropriation of Sylvia Plath…one of the more peculiar cultural phenomena of the 20th century.’[xv]

There are those who, in the Calvinist, desiccating vocabulary of Theory-speak, lithe and nuanced as a coroner’s report, conscript Plath’s writing as testament for a certain, cold-blooded form of Feminism. Mostly, this demonstrates how much a language of formulae can only degrade a language of spells – the creation of which relies on passion, instinct, and chance.

This is an extract from The Wind Pours By Like Destiny – Sylvia Plath, Asa Benveniste and the Poetic Afterlife, published by Unbalanced Books.

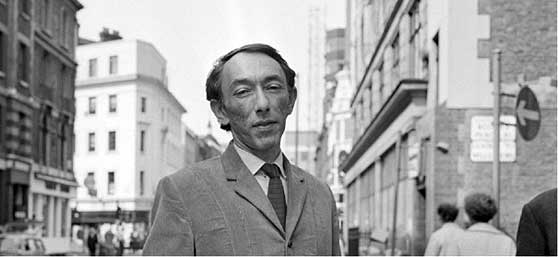

Images list: Asa Benveniste (date, location and photographer unknown), Benveniste’s grave in Heptonstall, Trigram Press advertisement in Ambit magazine (#58, 1974), Cover of Black Alephs by Jack Hirschman, cover design by Wallace Berman – published by Trigram, 1969, Aggie Falk and Asa Benveniste outside their bookshop in Hebden Bridge, Asa Benveniste at Sylvia Plath’s grave (both photos 1982 and courtesy of Alistair Johnson), Heptonstall, a cover image of Remains of Elmet by Ted Hughes, photo by Fay Godwin. Fay was once the wife of Tony Godwin, owner of Better Books in London, where English underground culture, including its poetry, was largely alchemized in the 1960s.

[i] Jeremy Reed, I Heard It Through The Grapevine, Asa Benveniste and Trigram Press, Shearsman Books, Bristol 2016. p.13.

[ii] Iain Sinclair, Lights Out For The Territory, Granta Publications, London, 1997. p.132.

[iii] Jack Hirschman, “Kabbala, Communism and Street Level Poiesis” in Mysticism and Meaning, ed. Alex S Kohar, Three Pines Press, St Petersburg, Florida, 2019. p.61.

[iv] Asa Benveniste, “As a Valediction”, Throw Out the Lifeline, Lay Out the Course, Anvil Press, London, 1983. p.7

[v] B.S. Johnson, “Sylvia Plath’s Ariel”, a review in Ambit, 24, 1965.

[vi] Interviewed by Peter Orr for the BBC series The Poet Speaks on 30 October 1962.

[vii] Al Alvarez, The Writer’s Voice, Bloomsbury, London, 2005. p.105.

[viii] Ken Edwards, UK Small Press Publishing since 1960: The Transatlantic Axis, writing.upenn.edu/epc/authors/edwards/edwards_press.html

[ix] poltroonpress.com/dead-poets/

[x] Roy Fisher, “At the grave of Asa Benveniste”, in The Long and the Short of It – Poems 1955-2010, Bloodaxe Books, Tarset, Northumberland, 2012. pp.193-4.

[xi] Interviewed by Peter Orr for the BBC series The Poet Speaks on 30 October 1962.

[xii] There were also some small children’s books, including The Bed Book and a number of limited editions. The Collected Poems won the 1982 Pulitzer Prize.

[xiii] Author’s interview with Frances Bruce, a former director of Calder Civic Trust, 12.02.22. The Trust had been contacted and asked if the path to Sylvia Plath’s grave could be signposted. The Trust wrote to Aurelia Plath for her opinion. In reply she objected to anything of the kind. Although she understood people wanting to see where her daughter was buried and that her writing and her life were ‘public’, the grave was ‘private’ and for the family.

[xiv] Frieda Hughes, “Readers”, POP! The Poetry Olympics Poetry Anthology, ed. Michael Horovitz, New Departures, London, 2000. pp.64-5.

[xv] Christina Patterson, “In search of the poet”, The Independent, 6 February 2004.

Excellent, informative read. Thanks, Jay.

Comment by Leon Horton on 7 January, 2023 at 8:20 pm