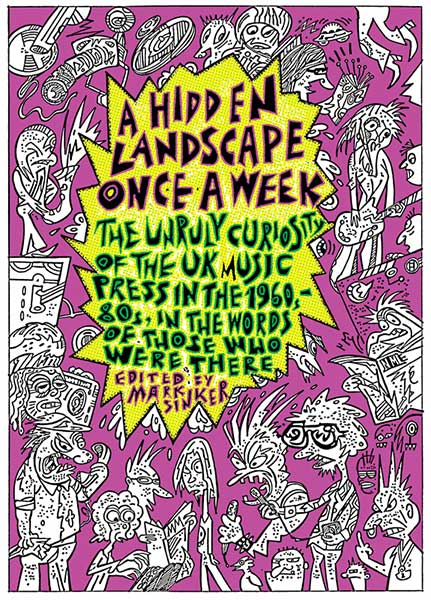

A Hidden Landscape Once A Week: The Unruly Curiosity of the UK Music Press in the 1960s-80s… in the words of those who were there, Mark Sinker (Strange Attractor)

It’s clear that there was some kind of golden era in the music press. This isn’t dewy-eyed nostalgia or revisionism: music writing documented rock and pop music countercultures as they emerged in the 1960s, and went on to draw on a hybrid of what became known as the ‘new journalism’ and cultural studies. By the end of the 1970s punk had been and gone, post-punk was in full swing, New Romaticism was on the horizon, and a new bunch of journalists had taken over the weekly music press, be they streetwise smartarses or pseudo-intellectuals. In their prime, Melody Maker, Sounds and New Musical Express not only covered a wider range of music, but also cult films and literature (take a bow the likes of Nic Roeg, William Burroughs, Antonin Artaud and J.G. Ballard), all through the theoretical lens of Walter Benjamin, Adorno, Foucalt or other favourites of the time. Where else would such pretentious cultural ponderings sit alongside an ‘interview’ with Howard Devoto being chased through train sidings at night by the writer, and John Gill comparing Weather Report and This Heat in a review of an obscure self-released LP?

Sinker’s book is based on the proceedings of a conference, edited transcripts of discussions and talks, with a few book extracts thrown in. It’s as much a celebration as a critique, and the one criticism I have of it is that it tends to put speakers with a similar type of speakers; I’d like to have seen a little bit more interaction between the cool and uncool, old hippies and postpunks, counterculture and pop fans. But in the main this is good stuff, that touches on business, race, the concept of the underground, pop and the mainstream, bohemianism, cult music, and social contexts.

Mark Williams claims that he and other journalists ‘were propagandists in a way, we found things that we liked and thought it was our mission to tell people about the, to spread that enjoyment’, whereas Barney Hoskyns is more personal: ‘I would say it’s entirely to do with one’s ego and wanting to see one’s words in print.’ Paul Morley wanted that to, but for him it was ‘always about ideas, great ideas’, coupled with the fact that he ‘love[d] the idea of really winding people up and provoking them, and changing my mind half way through a sentence to just put ideas out there.’

In a way ego and provocation are there from the beginning as catalysts: magazines such as Friends, Oz and IT were set up to document a culture whose participants thought was important, revolutionary and would change the world. In a way it did, but we all know how commodification works, and how aspirations and desires can be stifled. The diluted version of love & peace that was in place by the mid 70s provoked punk in musical revolt, urging resistance to the idea of musical accomplishment as well as the Tories in power.

There have been other attempts to contextualise and historicize the music press over the years, in books such as Nigel Fountain’s Underground: The London Alternative Press, 1966-74 (1988) or Paul Gorman’s In Their Own Write: Adventures in the Music Press (2001), but they mostly stuck to certain genres, locations or cultural labels (such as Fountain’s ‘Alternative’). Sinker’s book gathers up information and opinion about a much wider-ranging set of publications and genres, giving all the contributors a chance to sound off, make ridiculous generalisations (Barney Hoskyns, again: ‘Apart from people like Tom Waits […] everything just sounded horrible and dead and flat and synthetic.’ Really?), rant, argue and offer cultural and political interpretations from the safety of the 21st century.

But, the ‘unruly curiosity’ of the book’s subtitle turns out to be a pertinent phrase. The majority of writers and critics here are still both unruly and curious, still want to be heard, still listen to and write about music, still think about popular culture, still demand more than what is often offered to consumers. This book may initially appear to ne a nostalgia-fest but it looks around and forward as much as back, confidently and quietly demanding that music and music writing is to be taken seriously.

Of course, apart from a few exceptions such as Wire magazine, that writing won’t be appearing in any music magazines soon. One thing that sees most of the contributors to A Hidden Landscape agreed upon is how dull the ‘serious music’ approach of music monthlies such as Mojo and Q is; most of these contributors’ writing now appears elsewhere, in academic and cultural journals, or in mainstream newspapers, radio and TV. This book is a celebration, a critique, a discussion, a history, a conversation, an intriguing read, and a catalogue of possibilities – what more could you want?

Rupert Loydell