Auntie, why does your house smell funny?

Jumble Hole Clough

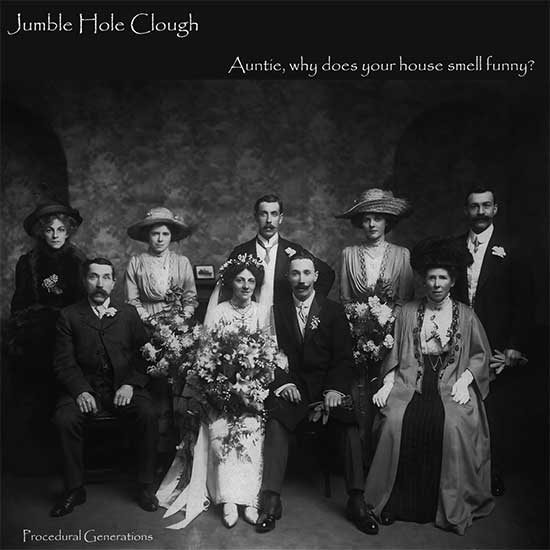

The album-cover of Jumble Hole Clough (aka Colin Robinson)’s latest album, Auntie, why does your house smell funny? is an old family photograph, taken back in 1912. When you look at it closely, all the people in it have a look of surprise mingled with slight puzzlement on their faces. It makes you wonder what was happening behind the camera. Perhaps the photographer had just completed a round trip in a time machine and was playing them Fanny Robinson’s great-grandson’s latest album on his phonograph.

The music of Jumble Hole Clough is, as Robinson describes it, ‘influenced by the landscape, industrial remains and experiences around Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire.’ The end result is a distinctive musical world that combines these elements with elements of his own dream-life and other flotsam and jetsam dredged from his subconscious. (His previous trilogy of albums dealt explicitly with dreams, but you get the feeling they’re an important part of much of his work). The dream-like quality of the music is no coincidence, I think. The area in question has, itself, the feeling of being some sort of humongous surrealist installation: the place names, the strange rock formations, a deserted radar station, an obelisk on top of a hill with a dark windowless staircase inside (overlooking the site of a former asylum), right down to the way the present is built on the wreckage of a past, the exact purpose of which, though industrial, is often not immediately obvious. And when we humans inhabit a place, our memories become embedded in the land. When they do, the landscape becomes a kind of external collective unconscious, full of archaeology the meaning of which is perhaps forgotten or, at best, half-understood: a kind of ‘jumble hole’, if you like (although the place, Jumble Hole Clough, really does exist). The associations we pull from it – waking, ancestral dreams – bear analogy with the dream-worlds we pull from our own subconscious minds and are, in turn, filed away there to re-emerge as future dreams. We talk about inhabiting an environment (environs – surroundings) but, in fact, we are, ourselves, part of the environment. We are, psychically and physically, part of the landscape, just as we don’t live on the Earth but, just like its rocks, are a part of the earth (and our thoughts, the fleeting electrical discharges in our minds, are no less part of it than lightening). This album – despite a brief field-recording made in Sevilla and the odd day-trip out – is, in a very real way, a rendition of a spirit of place.

I often wonder where Colin Robinson gets his titles from, much as I used to wonder how Iain M Banks created the names for his spaceships. As he says in his accompanying notes, ‘As always, the titles are of the utmost importance, they explain everything.’ Reading through them, it’s immediately apparent that the theme running though this album is death (and then, of course, we realise, all the characters in the album cover photo are dead). It begins with ‘A Christmas Card from Karlheinz’, which, perhaps, refers to the late composer, Karlheinz Stockhausen. Then comes Jackfield and Bedlam. This is not a reference to the famous London asylum but to Jackfield, a village in Shropshire and, perhaps, the nearby Bedlam Furnaces. These places, like the area around Hebden Bridge, represent the not-too-comfortable (for the workers, at least) seat of the Industrial Revolution in England. The lyrics describe it as ‘the land of the living dead’, the modern equivalent of a Hieronymus Bosch nightmare. And this sets the tone: what this album most reminded me of was a medieval danse macabre, itself an emotional response by the people of the time to the ravages of the Black Death, the modern corollary to this being Covid. And, like it’s medieval counterpart, it’s not a solemn affair. On the contrary, it laughs in the face of the Grim Reaper, albeit in a slightly off-kilter, unsettling sort of way.

If you’re still in any doubt, check out the title of the next track, ‘Friday 13th Part 12′, the 2009 American slasher film. I won’t go through all the titles – you can ponder the references yourself – but they do include ‘6am Marston Moor’. Marston Moor was, of course, a battle in the English Civil Wars in which the Roundheads killed four thousand Royalists, ending any chance of the latter controlling the North of England: you could describe it as a real life, seventeenth century, Friday 13th. Whether the ‘6am’ refers to a personal experience of Robinson’s, the morning before or the morning after the battle, is left to the imagination.

In his notes, Robinson says how much of the music began life through an ongoing exploration of generative music which began in 2022 with the album …and I think the little house knew something about it; don’t you? This becomes more obvious in the predominantly instrumental second half of this album, in which the macabre dance really gets underway, with titles like ‘May Day in the Ossuary Parts 1 and 2’ and ‘The Wondrous and Most Efficacious Electronium of Happy Valley’. There is an area not far from Hebden Bridge known as Happy Valley (it’s not just the title of a TV series) and intriguingly, going back to the first track, the electronium was one of Stockhausen’s instruments of choice. On reflection, I wondered if Robinson, like me, had been listening to the Today Programme’s interview with the composer on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, back in 1998. When the presenter asked him what he hoped to achieve before he died, Stockhausen replied, indignantly, ‘die? I’m going to live eternally!’ It could perhaps explain the Christmas card.

I once got lost in the fog on the moors in Robinson’s neck of the woods and found myself wandering down an uncanny, seemingly endless valley in which phantasmagorial shapes of ruined dry-stone structures kept looming up at me through the mist. After what seemed like an age, this ramshackle world gave way – almost imperceptibly – to the outskirts of Hebden Bridge. I often think of this experience when listening to Jumble Hole Clough.

TS Eliot’s Prufrock measured out his life in coffee spoons. It would be nice to think that, for a growing number of people, it’ll be Jumble Hole Clough albums. This, by my count, is the forty-fourth. Keep ’em coming.

Dominic Rivron

.