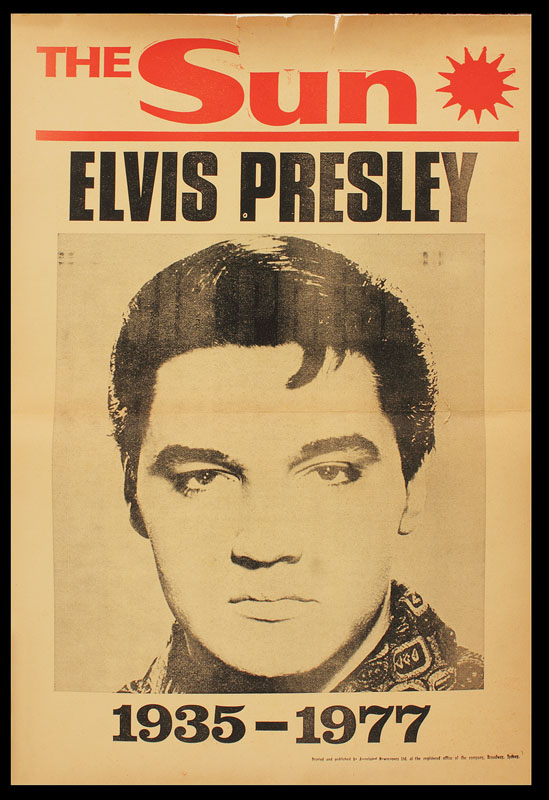

Ever after, that year of 1977,

we Americans abroad asked each other,

“Where were you when Elvis died?” a kind

of emotional milestone it was for us

travelers then, a tremor in the very

ground of our national identity.

What a shock seeing on the August streets

of Avignon the full-page headline

ELVIS EST MORT, my immediate response

to take a bottle of good Rhone down

to its namesake river and get weepily

sloshed on the vin and my sorrow, get

myself in a state that was not appreciated

by one particular Egyptian student

bunking in the same tented enclosure

as I at the Bagatelle campground.

It happened to be Ramadan, with

the young Egyptians fasting until dusk

at which time they would cook up the fish

caught down near where I was getting drunk.

It could have turned ugly, I with my

American notions of individual

freedom and the Egyptian boys’ strict

sense of Islamic law. Harsh words were

spoken, contempt flickered in that boy’s face,

near-denunciation. But the milder voice

of another, Khaled Rabie, prevailed,

mollifying the angry student and

explaining to me the offense taken.

I understood and learned, and things calmed down

in our little enclave. They shared their catch

with me, and I offered a sweet Provençal

melon, the best, I’d heard it said, in the world.

They commiserated on the death of Elvis —

I saw how everyone loved Elvis! — and I

felt less lonely in my grief. Next day,

when I left to explore the city,

the Egyptian boys swore that my belongings

were safe with them, and I found that I

had no trouble trusting them. I never forgot

that gentle peacemaker Khaled Rabie

who saved a defensive American

from his friend’s wrath and who, when he wrote

his address in my travel journal, urged me

to look him up if I was ever in Cairo.

Thomas R. Smith

.