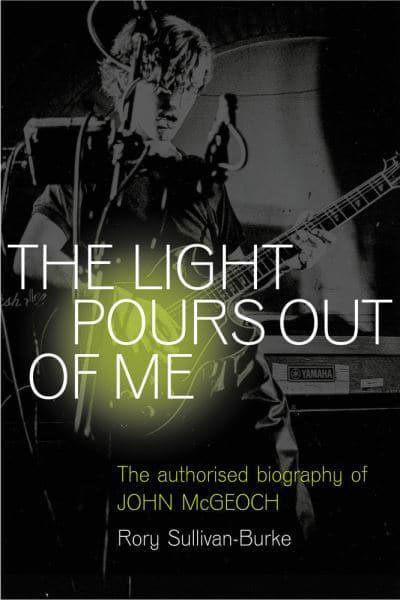

The Light Pours Out Of Me. The authorised biography of John McGeoch,

Rory Sullivan-Blake (259pp, £20, Omnibus Press)

‘Why is he important? It’s because he was him, because he played exactly those notes at the exact time that he did in the way that he did. That’s what it’s all about, really, and I don’t think I could explain it any other way.’

– John Frusciante (p 138)

If you don’t think you know the work of John McGeoch, you probably do. He made several albums with the very wonderful Magazine, re-energised Siouxsie & The Banshees and helped make their best albums (Kaleidoscope, JuJu and A Kiss in the Dreamhouse), was part of Steve Strange’s lucrative New Romantic project Visage, was as part of Richard Jobson’s The Armoury Show project, undertook session work for a wide range of projects, and played for later-period PIl (Public Image Limited).

McGeoch was part of the musical culture that made use of the possibilities that punk opened up, but hated the amateur pub rock thrash of that first wave of bands who knew only three chords and played naive songs of dissent and revolution. Magazine was one of the bands – along with others such as Simple Minds and XTC – that made it okay to have keyboards again (courtesy of Dave Formula), and literary pretensions. Howard Devoto, the front man and architect of the band, was arty, affected and strange; his oblique lyrics and original vision made him a perfect front man for the intriguingly layered music the band made. From the beginning, McGeoch’s guitar soars, weaves and unexpectedly moves throughout the songs, its gently flanged sound contrasting with the lead synthesizer’s artificial tones and the punchy bounce of the rhythm section. Despite their best efforts and much critical acclaim, Magazine never made it beyond being a cult band.

If Real Life, the band’ debut was tough and musically opinionated, their second album, Secondhand Daylight, was criticised as far too intelligent for the masses and was attacked by those who suggested the music, especially the stately instrumental ‘The Thin Air’ and the chilling closing track ‘Permafrost’, contained echoes of Pink Floyd’s progrock, which was simply not acceptable. Although many claim The Correct Use of Soap as their best album (I’ll stick with the first two, thank you) it was no more successful for the band, and McGeoch chose to move on, desiring more musical collaboration, publicity and promotion (by this time Devoto was not playing that game) and creative success.

McGeoch’s contribution to the Banshees was even more surprising, a kind of musical fairy dust shaken over the remains of the original band. Newcomer Budgie’s drums re-energised and changed the rhythm section, whilst McGeoch’s guitar moved the music away from their hard-edged early work towards a softer, almost psychedelic swirl of post-punk. I remember seeing this band play at Hammersmith Palais, how some of the time McGeoch played a teflon-coated semi-acoustic guitar, and how the studded leather jacket clad audience with their mohicans and attitude were aghast at that, along with the cheesecloth and crimped hair the band were sporting. But eventually they were won over by the sheer musical brilliance and energy of the band.

Although the Banshees were incredibly successful at that time, with hit singles and massive album sales, McGeoch had taken to drink and drugs as a way to stave off depression and the endless recording and touring the band undertook. It all came to a head in Madrid, where McGeoch was onstage in no fit state to play, although a second night was less crap than the first, which had seen McGeoch unable to remember specific songs or follow the setlist. Sullivan-Burke discusses the possibility of managerial sabotage here, with the guitarist deliberately being given a counter-productive valium to sober him up, but whatever the cause, McGeoch was out and Robert Smith of The Cure was in.

McGeoch ended up at The Priory, trying to make sense of his life, although it didn’t actually solve his addiction problems. He ended up being invited to be part of The Armoury Show, along with half of The Skids and Magazine’s original drummer. Richard Jobson imagined the band as a kind of post-punk supergroup, but there was little commercial interest, and sales of their 1985 album, Waiting for the Floods, were disappointing, and the band quickly folded, leaving McGeoch to once again rely on session work and royalties for income, and to continue to struggle with his alcohol and drug abuse.

Enter John Lydon, who had had his eye on McGeoch for a long time, and this time round was insistent that he join PiL, initially as part of a touring band on the back of Album. McGeoch had always been a fan of Keith Levene, PiL’s original guitarist and readily agreed. For a while things seemed to go okay, but McGeoch was enjoying touring less and less, and despite massive contributions to new PiL songs and albums, he more and more felt like an unrecognised second fiddle to Lydon, who made it obvious that he regarded PiL as his project. This was made even clearer in due course when Lydon signed a new solo contract, without the band, and without telling them. This, plus a major facial injury received from a thrown bottle which resulted in 40 stitches, meant McGeoch was without band again.

The book’s, and McGeoch’s, final chapter presents a kind of familial bliss with his second wife and daughter out in the country. McGeoch picked up his interest in visual art again (he had been an art student when Magazine started), took care of his daughter, cooked, cleaned and enjoyed domesticity. There was one low-key band project, Pacific, which came to naught, and an ongoing and sustained struggle with alcohol dependency as well as epilepsy brought on by the bottle incident. It was this that gradually got worse, producing periods of ‘absence’, blacking out and memory loss, and it was this in the end which killed him in 2004.

Sullivan-Burke’s book is a somewhat dry and unexciting account of McGeoch’s life and achievement. It’s thoroughly researched, and clearly he was supported by a wide range of musicians, critics and those who knew McGeoch, but I wanted more. Not kiss-and-tell stories, but more about the music, live and recorded, more about what informed and influenced McGeoch’s playing and compositional skills. Sullivan-Burke is good at the narrative of McGeoch’s life but only occasionally digs underneath to suggest causal possibilities. It’s all a bit earnest and inclined to nicety: whilst it’s clear McGoech could be gentle, supportive and engaged, Sullivan-Burke makes light of his addictive and macho sides. Worst of all is the final few pages of the book, which presents a compilation of tributes from those who knew, spoke to, or played with McGeoch, a kind of back-patting exercise that really puts paid to any idea of critical engagement. McGeoch was, as the back cover notes, a ‘remarkable guitarist who helped provide the soundtrack of a generation’, and he deserves a more remarkable biography than this thorough but rather well-behaved and polite version.

Rupert Loydell