What songs sing the sorrow of homelessness from Ginsberg’s metaphoric hydrogen jukebox?

Such mythology of the heavenly liberated hobo is often drawn from, for example, W.H. Davies (1871-1940) – the original supertramp. Davies, Newport, Wales-born wanderer of America, who famously settled in Gloucestershire, was frowned upon by Muse Colony of Frost (1874-1963), Lascelles Abercrombie (1881-1938), Edward Thomas (1878-1917) and their gang. They themselves lamenting loss of Brooke (1887-1915) then dear Thomas himself, both WW1 dead. Frost considered the different road to be taken around the daffodil woods west of Gloucester or at foot of Forest’s May Hill, the different paths of life (‘The Road Not Taken’, 1915).

Rambling old Welshman across the American landscape, Davies pre-dates songs & lamentations of the road. So perhaps turn to the railroad riders – Jack Black (1871-1932), ah, You Can’t Win (1926) – and myriad other lonesome travellers of the railroad night who sang in the cold loneliness under stars and from which emerged the American country folk blues. Then came depression-era rootlessness of the dust years of Steinbeck America (1902-1968) as seen through lens of Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) or lyric words of Woody Guthrie’s fascist-killing machine (1912-1967). Later still, Dylan of course (b.1941).

With a B-side of Lonely Tramp, Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry (b.1937) sung the bouncy hit Ain’t Got No Home (1956), later imitated in the shower for new generation by Corey Haim (1971-2010) in The Lost Boys (1987). Robert Johnson (1911-1938) had Rambling on My Mind (1937), but Elmore James (1918-1963) captured real tears of loneliness looking out on the grit streets, moaning ‘The sky is crying…can you see the tears roll down the street.’ (The Sky is Crying (1960)).

Perhaps it is in this very same street of tears whereupon the mythology of the supertramp wanderer crumbles.

Homelessness, a zenith of utter loneliness, is also the mark of desperation. Reality for the forgotten and overlooked. Unforgiving streets become home to the homeless, weary wanderers of dirt, drink, drugs and death. To live it is to be dehumanized. Dehumanized by state, hope, work. Dehumanized by all of us who pass with hardened gaze, fixed on some futile consumer culture comfort, some comparably pointless anxiety of our own.

That street of tears is the ground trodden by next generation Beat poetess Mimi German in her collection Beneath the Gravel Weight of Stars.

Forget your utopian freedom dreams of Walden; dropping out here is kick in the eye of reality. They’re the real poems of pain and searching for grace under hopelessness. Raw articulations of life-choice made only of necessity and loss. German is a grit queen of the outlaw rebel poet tradition, of the oral tradition of the Beats, Howling in anger and truth.

But let’s first scrutinise this contradiction, the Beat mythology of the supertramp and the freedom of Kerouac’s holy fellaheen, as compared to the true experience of life and death on the streets.

In my own ‘Benchsleepers of the World’ (Oblivion: 200 seasons of pain & magic (Gloomy for Pleasure, 2021)), I pondered the same thesis, contrasting this 20th century lore of the free wandering supertramp to the reality of homelessness. The Beats, we must conclude, use the term ‘beat’ as in ‘downbeat’ as metaphor for exhausted suppression of the disenfranchised brought upon by failure of consumerism to provide for all. But also tired and beat from life under all stale norms of expression, ways to live. And yet, at the same time, Kerouac uses beat as be’at as possibility of ‘beatitude’, as in beatification.

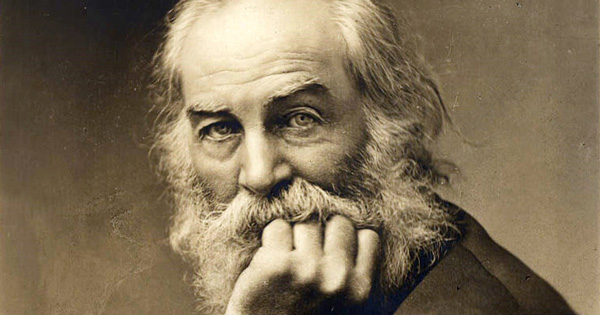

I’m happy to embrace that mythology – territory of Walt Whitman – and do so at the start of my own ‘Benchsleepers…’, only to explode it at the end: “but lonely old soul, lost soul, soulless soul, what kisses of the world have you tasted, apart from that of sourblacktragedy and ice?”

German’s scraping gravel poems live in that “sourblacktragedy”. She eats it. Spits it out, bloody and into our minds so that we might fleetingly taste the real grit for ourselves, antithesis of ‘Kubla Khan’s’ “milk of paradise” (Coleridge, 1816).

But Mimi’s not after your pity. Has lived through these stanzas in hard graft. Not as homeless herself, but as campaigner, activist and co-founder of the Jason Barns Landing, a transitional village and houseless community in St. Johns, Portland, Oregon. Cold, hard streetwork. The real deal. A defender.

‘The arts have always been a response tool to politics,’ she asserts, ‘to either shed light on what is happening or to create a way to navigate the harm that politics creates.’

Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) and The Dharma Bums (1958) are often referred to as calls to drop out and embrace the wandering. The Dharma Bums sought to start a backpack revolution. And for some I guess that was the dream. Even today, witness the big quit / great resignation since COVID-19, or the rise and rise of ‘van life’. The atomised of the social media age want out. But dropping out of the rat-race to live authentically is just a choice. Homelessness, on the other hand, is bereft of choice. It’s not the result of hedonistic romanticism, but the domain of desperation. Dharma Bums hiking up the Northern Cascades or the Matterhorn pondering a zen mind this is not.

But if we’re gonna entertain this myth at all then I think, in a way, Chris McCandless (1968-1992) has to be my patron saint of Beats, though no Beat himself…I guess all saints are unaware of their saintliness until it is posthumously bestowed. He left the consumerist life for the wandering in 1990. Went Into the Wild (non-fiction (1996) by Jon Krakauer, movie (2007)) and, in the Alaskan winter, died of starvation.

Compared to the free roaming life supposedly the topic of On the Road and The Dharma Bums, Chris’ story perhaps offers a warning against this notion of the supertramp Beat freedom. But that hitch-hike wandering is just one aspect, one interpretation of Kerouac’s novels. One pushed by marketeers of the publishing world or lazy critics. I’ve always argued that On The Road is, to me, about friendship whilst The Dharma Bums is about friendship and spiritual doubt. But, fine, let’s put that aside for a moment and entertain the popular conception of those books. If they’re merely about dropping out, then Into the Wild raises an alarm against the kind of conservative consumerist society which has now advanced so terribly that a wondrous boy could slip so easily away.

Either way, dropping out isn’t Mimi’s focus, even if she, in my opinion at least, has a spiritual and poetic link in form to the Beats and shares much of their outlook. In this collection the subjects of her eye are those for whom capitalism has failed. For whom bad choices, lack of support, and/or addiction have disabled opportunity; has rendered them bereft of choice. Bereft as a sub-class, and denied decency.

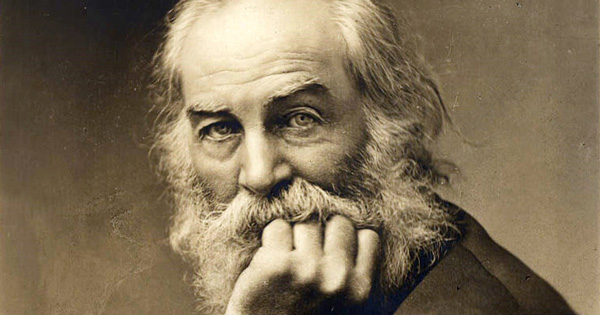

Another critique of the supertramp life and pre-dating Krakauer’s book and Chris – Alexander Supertramp – McCandless’ own setting out in 1990, is Agnès Varda’s (1928-2019) Vagabond (‘Sans toit nil oi’ / ‘With Neither Shelter Nor Law’, 1985); a movie where homeless death has never been so brutally, tragically and poignantly portrayed.

It’s my view that Mimi has added to that canon as a new, authentic voice, a next gen Beat voice mixed with – as poetic outlaws ought to be – sparks of grit and dharma, sparks of beatitude and acts of humanity. She’s one of the objectors to our age’s affront to kindness.

Of the two, Vagabond is the better movie in my opinion, even though Mona Bergeron is a fictional character based on an amalgamation of real homeless people Varda met during research, whereas McCandless was real. Vagabond wins by virtue of its crisp cinemaphotography, deft near-documentary style direction and a searing performance by 17-year-old Sandrine Bonnaire. Both movies, however, portray this balance of the so-called Beat ideal of freedom and the reality of tragedy. Both show the danger in the freedom they seek and Vagadond especially shows our society as one that refuses room to people who live authentically. Mona is asked, ‘Why did you drop out?’ to which she replies, ‘Champagne on the road’s better.’

So, in their respective ways, both movies break that supertramp myth. Both end in tragedy. And it is that tragedy which is so often the outcome for those on the streets who will have no movie. It is that reality which is the subject of Mimi’s poetry and the motive for her work on the Jason Barns Landing.

‘Jason Barns and Jason Barns Landing is a long story…I met Jason in the winter of ‘17. He was freezing and I convinced him to come over to my truck where I have supplies for folks on the street…After helping {him} into dry clothes and trading plastic bags that were his socks for true socks, he began to trust me. He asked me to start a village so they would have a chance at survival on the streets. He told me he’d die on the streets if we didn’t do this.’

‘While we were in discussions for how to make this happen, Jason died whilst collecting cans on the street in November, 2018, hit by a drunk driver.’

‘After his death, we decided to occupy land belonging to Metro and ended up housing 20 people in a transitional-style village that could provide stability for these unhoused people. The city harassed us deeply for nine months, that we had to move numerous times. We are in our third iteration today, still trying to get the city to leave us alone.’

Death will slip into you with ease down on the streets, in the cold winter fields, or among the snowy pines of Alaska. In all these stories, true or imagined, homeless deaths are unremarkable in a world of uncaring. The tragedy completes.

In Vagabond, Mona is questioned by an ex-homeless dropout who has rebuilt his life on a different path to liberty starting a family and small holding; he warns Mona ‘You chose total freedom, but you got total loneliness… My friends who stayed on the road are dead now or else they fell apart – alcoholic, or junkies. Because the loneliness ate them up, in the end.’

Such romantic ideals of freedom can so easily be nulled by this cruel, cruel existence crushing down on their subject with the weight of brutal reality.

As remarked earlier, Mimi’s subjects are homeless through circumstance, not choice. They’re victims of society, not dropouts. Victims don’t choose that kind of freedom. In that way, it’s not freedom at all, but raw brutality. It’s abandonment by society of what it regards as the dirty. A flightless bird does not choose to remain earthbound.

Yet society, with its casual judgements and suspicion, still somehow regards the homeless as people with choices; that they’re just drop-outs who’ve chosen not to work in regular jobs and create a home. But it’s difficult to do virtually anything when you’re addicted, suffering from depression; where you just feel so generally let down that you have no faith in even yourself. It’s then, when you’re at your lowest, most desperate, you find yourself cut off from all normal means of support. Adrift from our possible humanity.

With all that in mind, it’s so easy to be overwhelmed when reading work like this, the relentless tragedy. Back to On The Road and The Dharma Bums, and Kerouac – thru his alter-ego Sal Paradise and Ray Smith respectively – enjoyed a support network, was able to return home to mom or stay with friends and continuing the party; was free to explore his spiritual and literary existence with the relative safety net of fellow writer friends or family. The subjects in Mimi’s book have but only the kindness of strangers. That unsung body of people: volunteers. Activists.

As one of those strangers, Mimi is unapologetic: ‘All of the poems in this book are about the lives of unhoused people. I’m an activist, an organiser, and an advocate for unhoused people in Portland, Oregon.’

Beneath the Gravel Weight of Stars was launched at Revolutions Bookshop in Portland. ‘It’s a tiny store,’ says Mimi, ‘More of a small nook of revolutionary and radical books and authors. Poetry. Radicalism. Kerouac and Burroughs. Angela Davis. Audre Lorde. Whitman. Yeats. Local zines you’d never see elsewhere except at protests. Anyway, I emailed to see if I could set up my first reading at their place and that it would be an event where housed people sat alongside unhoused people, you know, to actually be in the same space, listening to poetry about the struggle to survive on the streets.’

‘Bringing housed and unhoused people together is incredibly important to me,’ she continued, ‘…it’s something I’ll continue to do no matter where I read in person. We have to remove othering. Remove the space that allows housed people to pretend to understand what they do not understand, help bridge that gap with reality, where humans meet humans over a cup of poetry.’

From the first line of the very first poem, these verses have a sense of place, the littered urban space: “shadows cross the wired streets” – the streets we readers roam for images and truth thru the poets’ eye (‘The Crossing’, pg. 7)… ”this is no house row” (‘No House Row’, pg. 10).

Ginsberg’s (1926-1997) “lonely old grubbers” (‘A Supermarket in California’, Howl & other Poems (1956)) roam in Mimi’s “vile loam of night” (‘When Are the Buds’, pg.24), “across the shatter beneath the gravel weight of stars” (‘The Other Side of the Coffee Shop Window’, pg.8).

With the refuse of modernity “tangled in the cling wrap morning sky” (‘No. 19 – earth on dry ink’, pg.9), these poems wreak with anger of Diane Di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters but with a somehow raw subtlety that’s hard to grasp, surely difficult to write. Reminds me sometimes of touches of Elaine Feinstein, albeit in a Beat mode with that keen holy unashamedness of outlaw poetics.

Each poem is justified in both left and right margins and spread across the width of a page so leafing thru presents like 26 tombstones of names left out to die in the cold night of shame – our shame.

She’s also a voice of hope in the dark chill streetlamp night. A voice that reaches out to those so dehumanised as to be even without their own reflection (Unsheltered, pg.21). Her work is more than support, it’s the activism that seeks the right to life, respect, and a home. ‘These folks are beautiful to me,’ says Mimi. ‘Folks I’ve met on the streets. So utterly real. With absolutely nothing to lose. Nothing to hide. Because there’s nowhere to hide. It’s what I write about, even when it’s not poetry directly about the unhoused, like the poem ‘The Scenic View’…

{not in Beneath the Gravel Weight of Stars, presented here by special arrangement}

German is also reflective with touches that allude to her reading of Castaneda: ‘Life is poetry. Life sucks. Life is suffering. Life is ugly. Yes, of course, there’s also beauty…’ she says. ‘Carlos Castaneda taught me that you have to live your life in a way where you really understand what it means to say that today is a fine day to die. Meaning, live! Neal Cassady taught me the same thing. Live life. Do what needs to be done so you have nothing left undone.’

And scattered among the Mimi pages is that zen-like calm you sometimes get from the Beats and the transcendentalists before them. Sometimes that calm comes as acceptance, fortitude and recognition of simple fortunes: ”no rain | no wet | the bone shiv of winter waits in the cracked lips of clouds | mean time thirteen cans is a free lunch” (‘No. 29 – opaque pastel on crepe paper’, pg.23).

It is the beauty of the barren lands that informs her next project: ‘I’m working on my desert poems,’ she says. ‘When I’m in the wilderness, I write about the desert. It’s an easy transition from the ugliness of the world. I’d much prefer the beauty of the open land to urban life… to live out there in the wilderness… There is a different song to be heard… The stars vibrate… wildflowers defying the bounds of living.’

Who isn’t beguiled by the real and metaphor of wildflowers in the desert night, cold dawns and dust-blood sunsets?

Indeed, the abstract cover of Beneath the Gravel Weight of Stars is well poised to reveal beauty in the darkness-mess: cerulean blue in a green smog clouding alive with neon streaks that scratch the stellar night, mess of cosmos with pockets of fire red and ochre debris. It reminds me of David Armitage’s music-derived art Songlines back in ‘97. Today his work seems to meld Bacon and Kandinsky but you can still spot techniques that hark back to Jackson Pollock, himself linked to the mid-20th century milieu from which the Beats also emerged.

I’ve referred to Mimi as a next-gen Beat, but she’s flattered by the accusation: ‘To be considered a new Beat poet? Fabulous! The most influential people in my life were Beat writers, including Whitman! Beat. The rhythm of the Beats. Yes, I share that. The disdain of the ‘norm.’ I rejected the 9-5 and all that fits into that a long time ago. I think my mother would attest to the fact that I was born this way. I’m not into borders or boxes.’

Walt Whitman, like Ezra Pound and William Blake, have all been a huge influence on the Beat Generation. Those greats and the muse within them continues to resonate in today’s next-gen Beats, as Mimi herself attests, ‘George Wallace writes in his poem, ‘The Poet’, “…inside his head jaguars prowl, jaguars and jackals”, and later in the same poem, “he speaks all languages, all the uttered phrases of lost nations are at play in his head, his brain is fire, his brain is smeared concrete, his brain is hieroglyphics, he lives in the tomb of the forgotten kings, his tongue is cave paintings, his will was written by a frightened child, and the city loathes him”. If we are lucky enough to have a reader, and then, a reader who admires or gets something powerful from our words, well, there’s the glory. But it resides within the reader or the poem itself.’

Wallace, lifetime National Beat Poet Laureate and current writer in residence at the Walt Whitman Birthplace, having read some of Mimi’s work, saw resonance with San Francisco’s Jack Hirschman. And, yes, there is a similar passion for justice in German’s work.

Mimi’s great at last lines, but I’m not going to share more with you; I don’t want to spoil your own reading. This collection deserves to be read widely, and shared. Experienced fresh. It’s in that first read where its power is most potent. Beneath the Gravel Weight of Stars communicates reality in a poetic style that is accomplished and which shines. It is art from desperation, and beauty out of sadness, regret and shame.

That shame is ours.

That we don’t do more. That shame is society’s: for walking by; for allowing civic authorities to act without civility; for accepting capitalism built to turn our hearts and minds away from the needy and broken.

They’re starting space tourism when the streets are littered with broken people. Who will sing for them?

Let’s add Beneath the Gravel Weight of Stars to the songs of sorrow, in poetic form, to Ginsberg’s hydrogen jukebox. Songs of tragedy, sadness, struggle and hope. For all poems, truly, are songs of the heart.

Review by Karlostheunhappy (facebook.com/karlostheunhappy)

Beneath the Gravel Weight of Stars is available from Amazon on both sides of the Atlantic or direct from the publishers at thepoetrybox.com $14

USA: facebook.com/JASONBARNSLANDING

UK: www.shelter.org.uk

This article first appears in Steel Jackdaw issue #7 summer 2022: please support this fantastic eco-arts magazine by buying the original.

“German is a grit queen of the outlaw rebel poet tradition, of the oral tradition of the Beats, Howling in anger and truth.”

Comment by Kevin Hester on 18 September, 2022 at 11:20 pmWho wouldn’t want to read it after that accolade.