Scotland, the Underground, and the Punk That Wasn’t Meant to Exist

page-34—Rezillos co- David Smythe

page-217-a—The Innocents by Tommy Reckless.

Never Trust a Hippy, the slogan that pretended history had been erased. Punk announced itself as a Year Zero, a complete severance with what had come before. Yet the speed with which many punks quietly reclaimed their Hawkwind, Pink Fairies and Amon Düül II records tells us what we knew, that punk did not emerge from nothing. It condensed decades of agitation, cultural sabotage and youthful rebellion into a sharper, more confrontational form.

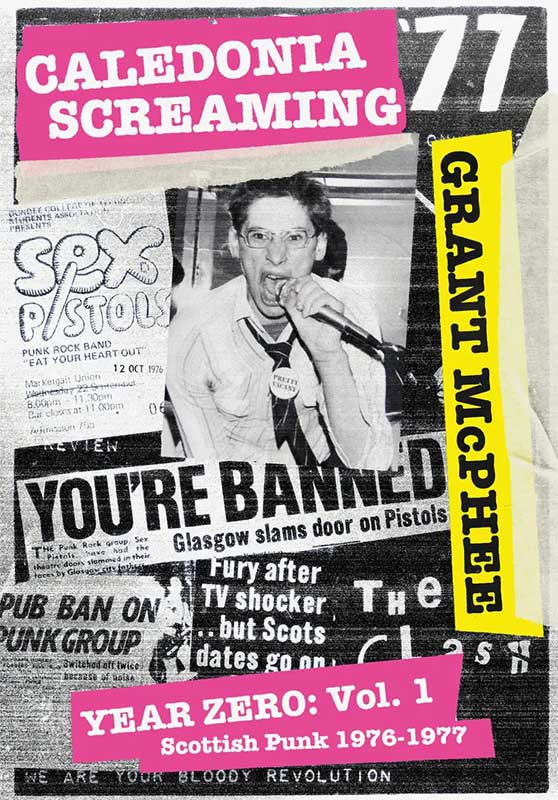

What remains far less acknowledged is Scotland’s role in shaping that earlier British underground — and the paradox that, having helped build the cultural and institutional conditions for London’s 1960s counterculture, Scotland did not experience punk-rock’s first explosion in the same way. This tension, between punk’s antecedents and its initial visibility in Scotland sits at the heart of Caledonia Screaming, my study of Scottish punk in 1976 and 1977.

In the 1950s and 60s, Scotland exported a remarkable amount of radical cultural energy south. Writers, poets, publishers, agitators, promoters and organisers moved between Edinburgh, Glasgow and London, helping to shape the ideological and practical infrastructure of the underground. These were not marginal figures either, they were central to 60s British counterculture articulating itself to the mainstream.

One of the most important of those spaces was Middle Earth, the psychedelic London club that rose from the vacuum left by Joe Boyd’s UFO, where the disruptive strands of the late hippy movement collided with provocation and anti-authority. What is rarely mentioned is that Middle Earth only existed because of two Edinburgh-based club promoters — the Waldman brothers — who temporarily relocated back to London’s to absorb themselves in the underground.

In the summer of 1967, Tyrannosaurus Rex played their first proper gig as a duo at Middle Earth, introduced by John Peel. Inside that moment sit two significant lines of punk’s genetic code from each member. On one side, Marc Bolan, future glam icon and a decisive and recognised influence on punk’s visual and musical stance. On the other, less established side is Steve Took, whose trajectory through the Ladbroke Grove scene and co-founding the Pink Fairies fed directly into the “angry hippy” strand that would heavily inform punk’s politics, speed and aggression. Pink Fairies, evolving from Mick Farren’s Deviants, and Hawkwind would all leave audible fingerprints on the later punk explosion.

Scotland’s presence in this darker London countercultural lineage was not incidental. The Process Church of the Final Judgement, one of the most visually and ideologically unsettling sects of the late 1960s underground, was effectively run by a Glaswegian, Mary Ann McLean. Its stark iconography, moral absolutism and confrontational public presence would later echo through punk visuals — most obviously in the work of Jamie Reid — and through industrial and post-punk culture via figures such as Psychic TV, co-founded by Renfrew emigre, Alex Fergusson.

Running alongside this was the curious importance of Scientology in Edinburgh, which hosted one of the highest-level centres in Europe. William Burroughs immersed himself in Scientology while visiting the city in the late 1960s, having first connected with its bohemian circles at the 1962 International Writers Festival. Around the same orbit moved Alexander Trocchi, Tom McGrath and others who were attempting, through the opaque Project Sigma, to imagine a transnational network of cultural ideas decades before the language of “networked culture” became familiar.

This then leads to the creation of International Times, the central platform of Britain’s late-60s underground. International Times co-founders included Glasgow playwright Tom McGrath (who also edited) and Edinburgh-based Jim Haynes, founder of the Traverse Theatre. It offered not just information but a way of thinking: a blueprint for underground culture as something self-conscious and politically charged. The DIY publishing methods and ideological framework carried by IT fed straight into the art-school world around Malcolm McLaren, himself a half-Scot, Vivienne Westwood, Jamie Reid (another half Scot) and Bernie Rhodes.

In other words, Scotland was not peripheral to the British underground that preceded punk. It was deeply embedded in its production, distribution and sensibility. Which makes what happened next all the more strange.

When punk finally arrived in 1976 as a media phenomenon, Scotland appeared not to ignite. There was no Scottish equivalent to the Sex Pistols, the Clash or the Buzzcocks at a national level. The Rezillos came closest to embodying the kinetic energy but the explosion itself seemed to happen elsewhere. From the outside, Scotland looked like an absence in punk’s foundational narrative.

But the reasons for this were not aesthetic. They were structural. By the mid-1970s, Scotland faced a profound deficit in cultural infrastructure. There were few rehearsal spaces, almost no independent recording studios capable of servicing new bands, negligible independent label presence (beyond the excellent and influenceial Zoom Records), minimal specialist press and, most crucially, a catastrophic lack of local radio provision. Pirate station, Radio Scotland in the mid-60s briefly attempted to address this absence, only to be banned by the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act. It would take until 1978 for Scotland to gain something approximating a national BBC radio station. By then, punk’s first wave was already passing.

Layered onto this was a uniquely aggressive relationship between the Scottish press and youth culture. From the 1950s onwards, moral panics framed each successive generation of young people as a social threat: teddy boys, rockers, mods, hippies, punks, ravers. The language barely changed. Youth culture, especially when connected to music was persistently coded as violent, working-class and deviant. The result was not mere tabloid hysteria but concrete obstruction: cancelled gigs, council bans and institutional hostility.

Through all of this, the influences of punk were fully available to Scottish youth. They saw the New York Dolls on The Old Grey Whistle Test. They read about the Ramones, Television and Johnny Thunders in the NME. Imported records circulated rapidly through well-stocked shops. The musical spark was present. What was missing was the ladder that converted inspiration into sustained activity. This created what appeared, from the outside, to be a vacuum.

Something did emerge though, between 1976 and 1977 what Scotland offered was not a carbon copy of London’s punk eruption but a unique and decentralised, youth-built DIY ecology. Without those inherited infrastructures from the earlier generation, young people were forced to construct their own. Bands formed without interconnected scenes; fanzines appeared without publishing cultures; promoters, photographers, designers and artists emerged without institutions to legitimise them. Entire micro-scenes developed in parallel, often unaware of each other’s existence.

In most other regions throughout the UK, punk plugged directly into pre-existing cultural machinery. In Scotland, punk was required to manufacture the machinery itself. This distinction is crucial. The absence of national media attention, the lack of integration into early punk mythology and the weak linkage to the earlier 1960s counterculture gave Scottish punk an unusual degree of autonomy. Because it was not being watched in the same way, it was not constrained in the same way. It was free to fail locally, mutate structurally and repurpose itself into something that outlived punk as a style.

From this period came not only bands but an enduring infrastructure: independent labels, venues, promoters, visual designers, writers and organisers. All orchestrated by the young. These did not vanish with punk’s first wave. They became the skeleton on which Scottish post-punk and independent music culture would be later built on — from Fast Product and Postcard onwards — eventually giving Scotland one of the strongest DIY traditions in Europe. Franz Ferdinand and, Belle and Sebastian have done far more for Scotland’s worldwide reputation than Scottish Tourist Boards. The image of Glasgow as ‘No Mean City’ has been firmly replaced in Japan, American and beyond by one of monochrome pictures and shy, late night coffeehouse attending youth in their stripey t-shirts, care of Belle and Sebastian album covers and music videos.

This is the central argument of Caledonia Screaming. Scotland’s punk did not fail to exist. It existed differently. Its early invisibility to those outside of Scottish youth was not proof of absence but evidence of incubation. Because it was not canonised in real time, because it was not folded neatly into the dominant London narrative, it evolved with unusual structural depth.

Scotland did not miss punk. It used it’s power and energy uniquely. It rebuilt it under conditions of hostility and scarcity. And in doing so, it laid the foundations for a culture of musical independence that continues to define its music to this day.

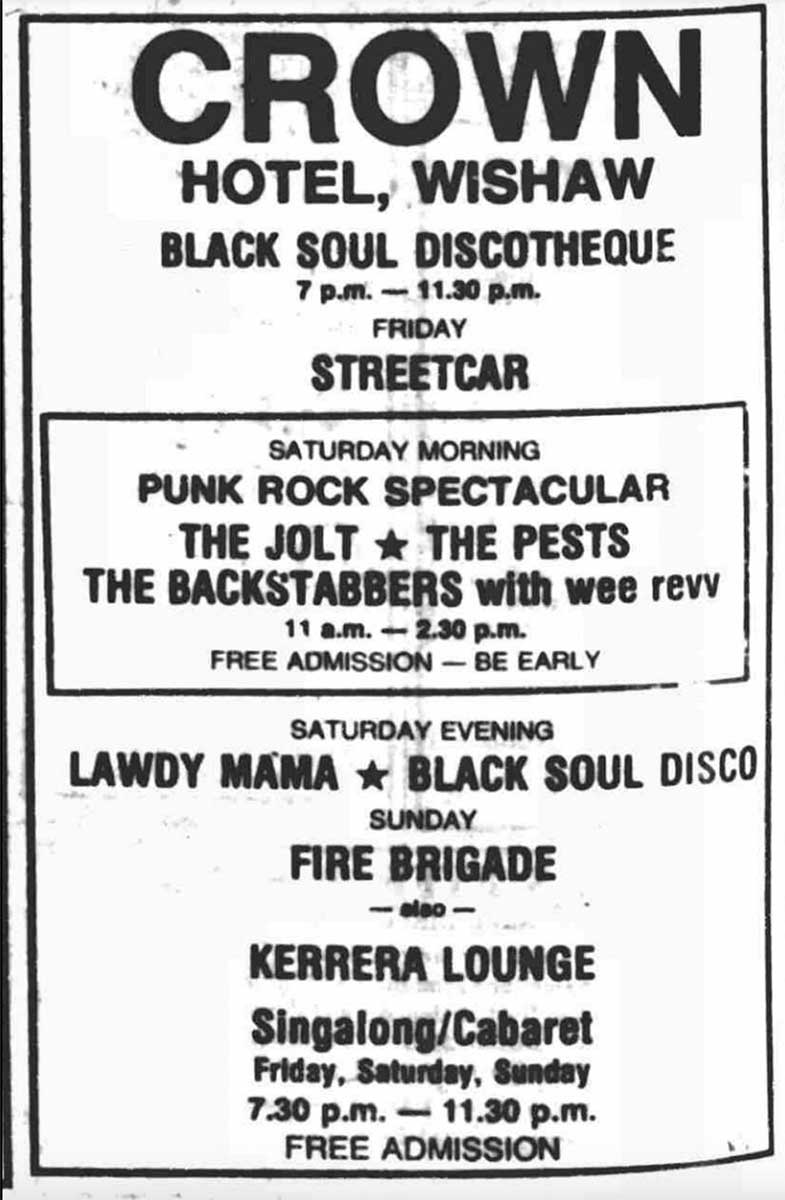

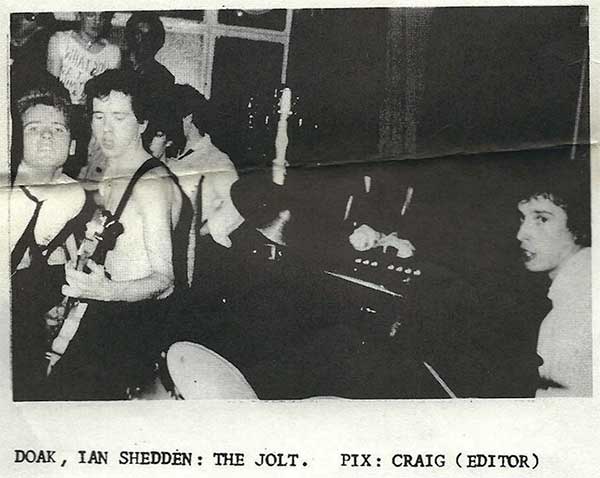

page-206 Crown Hotel

Grant McPhee

Buy the book at….

https://www.roughtrade.com/product/grant-mcphee/caledonia-screaming-year-zero-vol-1-scottish-punk-1976-1977

https://www.brownsbfs.co.uk/Product/McPhee-Grant/Caledonian-Screaming/9781738514991