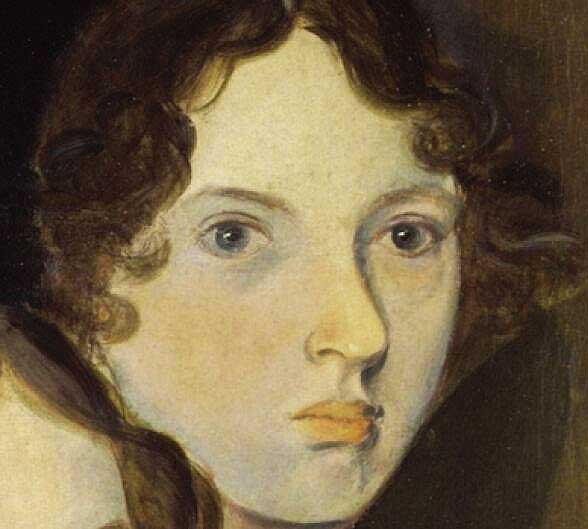

Emily Jane Bronte (1818-1848)

portrait by Branwell Bronte (detail)

…and the angels were so angry that they flung me out,

into the middle of the heath on the top of Wuthering Heights…

–Wuthering Heights, Vol I, Chapter IX

Describing a violent encounter at Wuthering Heights, Isabella Linton says to Nelly Dean “I was in the condition of mind to be shocked at nothing; in fact I was as reckless as some malefactors show themselves to be at the foot of the gallows.” This statement, perhaps, more than any other in Emily Bronte’s only novel, conveys the crucial character of the work; perhaps, also, it is the key to an understanding of the author’s frame of mind.

In her introduction to the book (1900) Mrs Humphry Ward referred to the character of Heathcliff as the product of ‘a deliberate and passionate defiance of the reader’s sense of humanity and possibility’. In fact, since its initial publication in 1847, the defiant tone of Wuthering Heights has attracted admiration, bafflement and outrage in equal measure; and today encompassing all media (including theatre, dance, music and film) it has achieved the status of a mythic text – rather like Frankenstein, Jekyll and Hyde, or Dracula.

From whence stems this peculiar, magnetic attraction?

It is often the case that the book is misunderstood on many levels.

Rather lamely, Charlotte Bronte tried to explain or defend he sister’s work as the product of a naïve, isolated, country girl, marooned in the wilderness of the Yorkshire Moors, the mere vessel of Fate or impersonal inspiration. Yet criticism of the book’s faults (usually moral) serves to point us toward further positive insights into this testament of ‘perverted passion and passionate perversity’. Certainly Charlotte was correct when she drew attention to the storm-heated and electrical atmosphere pervading the story, over which ‘broods the horror of a great darkness’ (Genesis 15:12). We know the novel caused some anger among many straight-laced souls, ‘indignant’, said Mrs Ward, ‘to find that any young woman, and especially any clergyman’s daughter, should write such unbecoming scenes and persons as those which form the subject of Wuthering Heights, and determined if it could to punish her.’ Typical English reaction!

We may imagine our author in some heavenly sphere, gazing down on our sorry, fallen world, possibly enjoying a quiet, sardonic smile, ‘half-amused and half in scorn’ at the expense of those critics and arbiters of taste, who, over time, have condemned or, alternatively, defended her work; she might smile, half in scorn, at the somewhat ludicrous appellations she has been awarded: ‘The Sphinx of English Literature’, ‘The Mystic of the Moors’ and so on.

But we would be wrong – it is rather unlikely that Miss Emily Jane Bronte resides in heaven.

For some, no doubt, heaven is a desirable residence, but for her, as for the heroine of her novel, it would be an uncongenial place of exile.

Initially, the book subverted Victorian expectations of propriety; it upset expectations about women writers and also the prim stereotype of the respectable clergyman’s daughter. Even now, Wuthering Heights is disconcerting in different ways. It seems that almost everyone has entertained misleading assumptions about the work. In her Preface to a recent (2003) edition Lucasta Miller explains how as a youngster she assumed that the novel was ‘the locus classicus of bodice-ripping romantic fiction’. However, she says, ‘I seem to have made an error as comical as that of Emily Bronte’s Lockwood when… he mistakes a pile of dead rabbits for his hostess’s pet cats.’ Miller’s phraseology here points to a comic factor; but what form of comedy is this?

A dark comedy no doubt, even ‘gallows humour’. In Lightning Rod, an introduction to his Anthology of Black Humour, Andre Breton illustrates this with a well-known anecdote, borrowed from Freud; of a condemned man who led to the gallows on a Monday morning, exclaims ‘What a way to start the week!’ This darkly ironic, mirthless humour, the anarchic subversion of expectations, upending preconceptions of life and literature whilst also making us laugh is a matter of ‘attitude’; an attitude which may, according to Mark Polizzotti, take the form of ‘both a lampooning of social conventions and a profound disrespect for the nobility of literature’. In Emily Bronte’s work, including some of her poetry, there is abundant evidence of ‘attitude’, this predilection for ‘savage’, ‘gallows’ or Black Humour and a devastating, nihilistic cynicism forming the base of her particular, uncomfortable, convulsive aesthetic. Here, says Breton, following Leon Pierre-Quint, is a way of affirming, above and beyond ‘the absolute revolt of adolescence and the internal revolt of adulthood’ a superior revolt of the mind.

Indeed, a superior revolt of the mind. From a historical perspective it might be noted that this particular form of humour has uniquely English (or Anglo-Irish) roots, as Breton correctly identifies Jonathan Swift as the original inventor or precursor. Swift, he says was a man who ‘grasped life in a wholly different way, and who was constantly outraged’. His work embodied a ‘remarkably Modern spirit’, due to ‘the profoundly singular turn of his mind’. Consequently ‘no body of work is less out of date’. We can with confidence say the same about the work of Emily Jane Bronte.

The broad outline of Emily’s brief life is quickly told: she was born in 1818, the fifth of sixth children. The family was then living in Thornton near Bradford, West Yorkshire; her father was the Reverend Patrick Bronte and her mother Maria (nee Branwell). In1820 the family moved to Haworth, taking up residence in the old parsonage house. In 1821 her mother died and her mother’s sister, Elizabeth (‘Aunt Branwell’, a ‘strict’ Methodist), moved in to maintain the household and help bring up the children.

In 1824 the six year-old Emily attended the Cowan Bridge Clergy Daughters School, founded in 1823 by the Reverend Carus Wilson. Wilson was a Calvinist whose religious views would have been even stricter than those of Aunt Branwell (an Arminian Methodist). The regime was very harsh and the following year, after an outbreak of typhoid caused the death of her two older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, she was removed from the school. Cowan Bridge was the basis for the grim ‘Lowood Institution’ described by Charlotte Bronte in Jane Eyre. It is very likely that these experiences would have had a profound, almost traumatic, effect on the young Emily. In 1835 she attended Margaret Wooler’s Roe Head School, Mirfield for three months. In both of these institutions she was unhappy and always returned to the apparently self-enclosed world of her family circle. Her first extant poems date from this period. Then, in 1838 she was employed as junior teacher at Miss Pratchett’s Law Hill Girl’s School at Southowram near Halifax. While there Emily continued to write poems and, it is said, began to develop the ideas which eventually surfaced in Wuthering Heights. High Sunderland Hall, a nearby seventeenth century manor house, with weirdly baroque decorative features and inscriptions, made, it is claimed, a particular impact on the young teacher’s imagination.

With her sisters Charlotte and Anne plans were made to establish a school at Haworth. In 1842, as part of this project, Emily accompanied Charlotte to Brussels where they both attended Madame Zoe Heger’s Pensionnat de Demoiselles with the objective of improving their languages. Emily stayed in Brussels for about nine months (Feb-Nov) where she made ‘rapid progress’ in French, German, music and drawing, returning home with Charlotte in early November after the death of Aunt Elizabeth. Emily then flatly refused to go back to Brussels and remained at Haworth in the role of housekeeper while Charlotte returned to the pensionnat to continue her studies.

Later, back in England, Charlotte discovered Emily’s poems in her notebooks and eventually persuaded her to join in a joint publishing venture. The subsequent volume Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell was privately published by Aylott & Jones in 1846. Wuthering Heights was published by Thomas Cautley Newby in 1847. Emily, who for the duration of her short literary career was known to the public as Ellis Bell, died on 19 December, 1848 at the age of 30. Her illness (‘consumption’) and state of mind has long been the subject of speculation: was she Anorexic? Did she have Asperger’s? Did she suffer from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder? Even the dimensions of her coffin (16 inches wide, 5 foot 7 inches long) have become the subject of research. We have one last memory of Emily (or ‘Ellis Bell’) ‘leaning back in his easy chair drawing his impeded breath as he best could, and looking, alas! Piteously pale and wasted…’ listening, half-amused, as Charlotte read aloud from the North American Review where she/he was described as ‘a man of uncommon talents but dogged, brutal and morose’.

Her sister, Anne, died the following year in 1849 and a new edition of Wuthering Heights with selections of her poetry (edited by Charlotte Bronte), appeared in 1850. Charlotte herself died after pregnancy complications in 1855.

It is reported that Emily ‘never bothered to converse with people who did not interest her.’ According to Charlotte, the novelist Ellis Bell sometimes smiled, but ‘it was not his wont to laugh’. In Brussels she cut a singular figure, with her ‘old fashioned and somewhat dishevelled clothes’ and ‘dreamy look’. It seems the other young ladies found the Bronte girls odd, particularly the strange appearance of Emily ‘who never followed the fashions’ and favoured straight skirts and outmoded wide gigot sleeves ‘when the vogue was for the opposite.’ But, as Constantin Heger observed, ‘Her powerful reason would have deduced new spheres of discovery from the knowledge of the old’. Defined by her ‘upright, heretic and English spirit’, Emily has always exerted a fascination for critics and biographers her persona and character somewhat distorted by an undeserved reputation for ‘strange innocence and spirituality’, to quote Mrs Humphry Ward, who also drew attention to a strength of will and imagination which appeared ‘inhuman and terrible’ to many readers and some who met her. The only pictorial image we have of Emily is an unsmiling girl of about sixteen with a distant but intense gaze, staring out of the picture, and evading eye-contact with the observer. This detail from of a group portrait (known as ‘The Pillar Portrait’) made around 1834 by her brother is the only authentic image of Emily we have, as all others are disputed, including the so-called ‘Profile Portrait’ which may, in fact, be a picture of Anne.

Sister Charlotte was much in awe of Emily in her guise as poet and novelist Ellis Bell, the embodiment of a ‘strong original mind, full of strange though sombre power…’ who often preferred the company of animals to human beings and who found in bleak, moorland solitude ‘many and dear delights’ including the decisive experience of a rare form of liberty. Charlotte went so far as to say ‘Liberty was the breath of Emily’s nostrils; without it she perished.’ Mrs Ward, she herself a novelist of repute, leaves us a vivid image of this ‘wayward, imaginative girl, physically delicate, brought up in loneliness and poverty’ immersed in literary interests. ‘One may surely imagine’ surmised Mrs Ward, ‘the long, thin girl bending in the firelight over these pages from Goethe…’ She is reading, it would appear, a recent translation of Dichtung und Wahrheit from a current edition of Blackwood’s (1839).

When she asserted that Wuthering Heights was the ‘epitome of a whole genre’ and of a ‘whole phase is European feeling’, Mary Augusta Ward placed welcome emphasis on the cultural context of Emily’s writing. A context which her contemporaries, unduly influenced by Mrs Gaskell’s and Charlotte Bronte’s image of the isolated semi-rustic, passive, young authoress (the unwitting conduit of shocking inspiration only explained by a kind of mystical naiveté), found expedient to ignore. Modern scholarship has long understood that this has been extremely misleading. The sisters were immersed in the cultural trends of the age and read widely, although their preference was clearly for Romanticism, rather than the socially-conscious Realism then fashionable. Emily’s poetry and fiction show traces of her chosen influences: Byron, Shelley, Coleridge, De Quincy, Cowper, Carlyle, Scott, and Wordsworth among others. Despite this, she remained true to her own unique vision, fusing these English Romantic trends with her own Christian upbringing (Milton, The Bible) and German Horror. Wuthering Heights is, in fact, pure Sturm und Drang, albeit with a particular North English twist (spoof dialect, local folklore), and her distinctive sardonic, ‘dry, saturnine humour’. It was a paroxysmal revenge melodrama, a classic of the ‘literature of transgression’; a toxic compendium of foul language, legal chicanery, amorality, dereliction, domestic violence, hysteria, hauntings, dreams, hallucinations, cruelty to animals, child abuse, moral degradation, forced marriage, sadism, male inadequacy, ‘monomania’, alcoholism, class snobbery and implicit sibling incest, not to mention low-church fanaticism, witchcraft, necrophilia and disease, all set in a remote, inhospitable landscape of ‘bleak winds, and bitter northern skies, and impassable roads.’ Catherine Earnshaw’s love-obsession for the alien ‘gypsy’ foundling anti-hero Heathcliff (a ‘fierce, wolfish, pitiless man’, the archetypal Byronic demon lover; an Imp of Satan, an ‘incarnate goblin’, a psychopath, a ‘moral poison’ or Monster From The Id; part vampire, part werewolf with, according to the rather impressionable Isabella, ‘sharp cannibal teeth’) is an inhuman, ambivalent compulsion eventually transformed into a self-destructive death-wish. Both protagonists starve themselves to death. This latter theme being, possibly, an amplification of one of Emily’s own traits; it is said that, when angry or unhappy, she might withdraw into silence and go on hunger strike as an act of defiance.

When Mrs Humphry Ward refers to the author’s ‘deliberate and passionate defiance of the reader’s sense of humanity and possibility’ she was attempting to itemise aspects of the novel seen as failings and faults like ‘monstrosity’ or ‘mere violence and excess’, yet, without this frame of mind, this ‘passionate defiance’ the novel would lose it’s essential, that is, its excessive, character: recall that scene where Cathy and Heathcliff observe the Linton children in the midst of a tantrum: ‘Isabella – I believe she is eleven, a year younger than Cathy – lay screaming at the further end of the room, shrieking as if witches were running red hot needles into her.’

This ‘deliberate and passionate defiance’, this reckless condition of mind ‘to be shocked at nothing’, is no aesthetic flaw; it is, rather, the very source of Emily Bronte’s unique vision. Wuthering Heights is a full-frontal assault on the cultural norms of literature and our idealised, complacent view of reality. Perhaps Miss Emily Jane Bronte had a cunning plan: to outrage the reader by exposing the psychopathology of the human condition, by deploying ‘a complete science of human brutality’ to quote Edwin Percy Whipple of the North American Review (October, 1848). Perhaps she was satirising our socialised sense of propriety and unquestioned assumption of normality.

For Rosemary Jackson, Wuthering Heights is a prime example of ‘Female Gothic’, a nineteenth century mode of women’s writing initiated by Mary Shelley. Female Gothic comprised a ‘violent attack on the symbolic order’ (the terminology is Lacanian) utilising non-realistic techniques such as sensationalism, melodrama, romance and fantasy to disrupt the ‘monological’ vision of patriarchal society, the ‘symbolic order of modern culture’. These women writers were seeking to achieve a ‘breakthrough of cultural structure.’ Yet it would be wise to listen to Pauline Nestor when she says that, rather like her anachronistic dress sense, Emily’s novel stands outside the fashionable literature of her day. She had no interest in writing a ‘novel-with-a-purpose’ or a polemic on the state of ‘the people’, or any kind of well-meaning exploration of ‘community’. Emily was no feminist, says Nestor, her strengths were ‘personal and idiosyncratic’ her work was devoid of ‘partisan politics’ with no sense of shared ideology or a ‘common cause’. Again, we may suggest that this rejectionist attitude, this idiosyncratic line of thinking, is a great strength; one of the character traits that makes Emily’s work always ‘modern’, forever compulsive, undiluted by transient, didactic distractions.

Much has been made of the childhood relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff, wild children of the moors or young savages, inhabitants of a sovereign domain of untrammelled liberty or the ‘free play of innocence’; although in the book rather less is made of this than we are lead to believe by enthusiastic critics. For Georges Bataille this is the core concept of Wuthering Heights seen as a campaign of revenge waged by Heathcliff to regain this childhood kingdom and his lost love, even though Catherine’s love for Heathcliff is strangely un-erotic and almost a form of unconscious psychic projection. Certainly a key turning point in the story is when he overhears Catherine telling Nelly that marriage to him would degrade her social standing. He runs from the house in rage and disillusion. An incident probably inspired by a similar moment of rejection in the early life of Byron (Moore’s Life Of Byron was published in 1830).

For Bataille, Emily Bronte was the object of a ‘privileged curse’ through her ‘profound experience of the abyss of Evil’. He defined the story as ‘the revolt of Evil against Good’. In Bataille’s terminology ‘Evil’ is ‘essentially cognate with death’ and ‘Good’ is everything that supports the system of ‘reason’ as ‘calculations of interest’ for the benefit of a collective ‘will to survive’; a variation on the long-standing Socratic philosophical-moral formula which postulates Reason as virtuous and preaches ‘virtue’ as the only route to human happiness. In her novel and through the character of Heathcliff, Emily explored an alternative viewpoint in which virtue plays no part and happiness is found through revenge and power over the weak. Bataille says the ‘wild life’ of the children ‘outside the world’ enables the ‘basic conditions of poetry, of a spontaneous poetry…’ For some readers this leads to explaining Emily’s work as a form of ‘pagan’ or pantheistic nature worship – although justified by her Romantic influences, in the end this is just another anodyne normalisation strategy which quickly morphs into the mythic ‘mystic of the moors’ scenario. Bataille, on the other hand, saw Emily as an example of a poete maudit in the same category as Sade, Baudelaire and her near-contemporary Edgar Alan Poe.

She was cursed with ‘an anguished knowledge of passion… the sort of knowledge which links love not only with clarity, but also with violence and death.’ It is certainly the case that in her only novel, and in her poetry, we find an overwhelming fixation on the subject of death. This is not surprising given the circumstances of the Bronte family, haunted by illness, bereavement and tragedy, and vulnerable also, via conventional channels of enculturation, to a strictly Protestant, non-conformist influence which accentuated an idea of death as a transcendental phenomenon, together with a very real prospect of Eternal Damnation. At a young, impressionable age Emily would have been exposed to all these influences, especially at Carus Wilson’s school. Wilson was known as an ‘excessive’ Calvinist Evangelist an adherent of the doctrine of predestination who frequently preached on the topics of ‘humility’ and the ‘deaths of pious children’. The girls were subject to a harsh, ascetic regime that included the learning by heart of long Biblical texts and many other shocking privations imposed in a damp, unhealthy environment. Given the added nightmare of the deaths of her two sisters it is very plausible that these circumstances had a traumatic and lasting impact on a vulnerable, homesick six year old. It is likely, too that she found some corroboration in this fatalistic worldview from the life and poetry of William Cowper who, prone to phases of insanity, haunted by the early death of his mother, believed he was doomed to Eternal Damnation and thought that God demanded he sacrifice his life by suicide.

Together with Poe, Emily Bronte counts as a Navigator of Death (Thanatonaut); all her work is haunted by ‘the sea of death’s eternity’ (‘The Night of Storms has Passed’) and permeated by an apocalyptic/eschatological theme of death both as a lasting refuge from the horrors of life and as a transition to a hyper-real mode of perceptual transfiguration.

It has been suggested that Poe saw his poetry as a ‘voyage of exploration, an attempt to conjure up, dramatize and discover the world that exists beyond death.’ (Richard Gray). In Emily’s poem ‘A Day Dream’ she writes ‘rejoice for those that live/ Because they live to die.’ However, this not a simple case of morbid fascination, as we may discern other influences, such as Shelley’s visionary Neo-Platonic Romantic poetic theory (the lifting of the veil), as well as her own Protestant inheritance, through which this fascination for death is refracted. In her untitled poem known by the line ‘I am the only thing whose doom’ (1839), Emily discards all earthly consolations, even hope itself, and finds mankind ‘hollow servile insincere’. Yet, she finds in herself the same corruption: ‘But worse to trust my own mind/ And find the same corruption there’.

These sentiments may echo the moral framework of ultra-Protestant thinking where the status corruptionis is the fundamental, basic state of humanity in a fallen world; a world where man stands in a negative relation to God, or even against God. A position implied in the Catherine-Heathcliff relationship, and even, perhaps, in the way that Cathy Linton (the Younger Cathy, Catherine’s daughter) is fascinated by the Fairy Cave and would appear to practice the dark arts of Black Magic (she is occasionally referred to as a witch or an ‘accursed’ or ‘damnable’ witch. She even threatens the inhabitants of the Heights with the traditional maleficent practice of sticking pins into human figures). For fundamentalist Evangelicals like Carus Wilson it is probable that his fixation on the concept of salvation was cognate with a similar fascination for sin together with a horror of superstitious ‘abominations’ as defined in Deuteronomy 18. As Max Weber has shown, the overarching project of salvation religion has been the de-magification or disenchantment of the world (entzauberung der welt), so the references to folklore and witchcraft may well be symptomatic of the wider, defiant tone of Wuthering Heights part of an unspoken quest to regain the enchantments of a pre-moral universe of Animism and inhuman forces. As Bataille has said elsewhere, with reference to both Nietzsche and Andre Breton; magic, like Catholicism, is one of those traditions that ‘give us a slightly uneasy image of the very ancient foundation of non-moralist religion’. The greater the moral power of salvation, the more weight must be attributed to Sin and the ‘abominations’ of idolatry and witchcraft. This great weight of Sin ensures the believer finds the Fall of Man to be absolute and finds human existence to be a condition of pure and total Evil from which there is no escape. The radical rift between God and Man, between humanity’s pre- and post-lapsarian existence is so great, the externality and incomprehensibility of God is so absolute, that affliction and anxiety, depravity and horror comprise the totality of the sinner’s life, for, as the Good Book says, ‘the wages of sin is death’ (Romans 6:23).

It is easy to read Wuthering Heights in the light of this post-lapsarian state, and it is the case that almost all of Emily Bronte’s poetry conforms to a similar, if ambivalent, pattern. Yet it is also likely that Emily, wrestling with these eschatological-ontological themes as she ‘worked through’ the side-effects of her childhood traumas – particularly the Cowan Bridge disaster – was not entirely subservient to the strictures of moral damnation, even though she used the tropes and vocabulary of her religious upbringing to explicate her agonistic worldview. How could it be otherwise?

There will always be anti-secular apologists for faith who will claim or reclaim Emily for their theological agendas. This will range from the quasi-New Age characterisation of an isolated ‘mystic’, a ‘heretic’, or a ‘visionary’ nature poet, to those who see her as a forerunner of the postmodern, post-secular ‘return’ of religion, mediated by the casuistry of theological notions such as the ‘apophatic , unnameable and ineffable’. Her poetry corroborates Bataille’s summarisation of her character: ‘Though few people could have been more severe, more courageous or more proper, she fathomed the very depths of evil.’

In the poem ‘How Clear She Shines’ Bronte dismisses Life as a ‘labour void and brief’, she says that Hope is nothing but a ‘phantom of the soul’, while existence itself is but the despotism of death. However in ‘Honour’s Martyr’ she states a personal credo of passionate defiance: ‘Let me be false in other’s eyes/ If faithful in my own.’ Consequently this means that, as Emily penetrates further into her creative life, she rejects the ‘world without’ with its guilt, hate and doubt, and ‘cold suspicion’. Instead, she exalts the ‘world within’ the world of her imagination, (sometimes envisaged as an angelic personification), ‘Where thou and I and Liberty/ Have undisputed sovereignty’. She breaks away from the shackles of inherited, tyrannical belief, even though she faced condemnation in a fantasy trial (‘Plead For Me’) where her prosecutor is Reason ‘with a scornful brow’, who mocks her overthrow, and comes to judgement ‘arrayed in all her forms of gloom’. In a scenario that corroborates Bataille’s exposition, the poet implores the ‘radiant angel’ of her Imagination to speak against Reason on her behalf, uttering a plea for one who has ‘cast the world away’, who has ‘persevered to shun/ The common paths that others run/And on a strange road journeyed on…’

This ‘strange road’ is surely an immersion in the creative process, as she longs to ‘cast my anchor of desire/ Deep into unknown eternity’ (‘Anticipation’). Even though she may be tormented by strange visions that ‘rise and change/ And kill me with desire…’ (‘The Prisoner [A Fragment]’) Emily Bronte, wilfully or not, made some of ‘those excursions to the bottom of the mental grotto’ to which Andre Breton refers in Lightning Rod his introduction to Black Humour. As Bataille said, it is wrong to see the poetry as revelations from the world of the ‘great mystics’, even though ‘the imprecise world which the poems reveal to us is immense and bewildering’. Emily’s world ‘is less calm, more savage’ and, crucially, its violence is not ‘slowly reabsorbed in the gradual experience of an enlightenment’; far from it. Emily, who rejected as vain ‘the thousand creeds’ by which humanity consoled itself (‘No Coward Soul’), who was uninterested in mystical ‘enlightenment, saw Wuthering Heights as an assertion of outrage, a reversal of theological-moral norms and an expression of her ‘passionate defiance’, an attitude of mind possibly derived from the traumatic events at Cowan Bridge and the deaths of both her sisters and her mother. The last thing she was interested in was ‘enlightenment’, an unnecessary aspiration for a damned poet who has lifted the veil of mundane existence only to reveal a destitute landscape where, to quote her sister Charlotte, ‘every beam of sunshine is poured down through black bars of threatening cloud.’ As Lucasta Miller says, the tendency of the book is a constant ‘striving beyond itself’, but what the book does not do is ‘offer a conventional moral standpoint’. Instead Bronte offers a ‘visceral’ depiction of psychic extremes and anti-social criminality without the consolation of a moral compass. In this world of ‘threatening cloud’, the radical externality of God ensures that all morality is meaningless, all existence chaotic and pointless.

These are forays into dangerous territory, and, for Emily, this forbidden domain was the psychic landscape of Stanbury Moor and her final destination was Ponden Kirk (‘Penistone Craggs’) a massive outcrop with a ‘ceremonial passage’ (‘Fairy Cave’); a site, rich in local folklore, hinting at chthonic forces and a primeval world of dread beneath or beyond mundane reality as depicted in the story. It is tempting to see this gritstone prominence as the topographical epicentre of Emily’s psychic universe and, as ‘Penistone Craggs’, it functions as an understated focal point in the fictional domain of Wuthering Heights. Even though in the overall scheme of the novel Penistone Craggs is a minor detail, it is well to recall that, according to Freud, the mechanism of displacement ensures the most essential elements of a dream are represented ‘merely by slight allusions’. The young Cathy Linton is particularly attracted to the abrupt descent of the outcrop, ‘especially when the setting sun shone on it and the topmost Heights; and the whole extent of the landscape besides lay in shadow …“And what are those golden rocks like, when you stand under them?” she once asked.’ Later, she announces that, one day, when she is older, “I should delight to look around me from the brow of that tallest point.”

Perhaps it was here, on some solitary excursion to ‘the brow of that tallest point’, that Emily experienced an anti-epiphany, a sudden counter-Calvinist turn of mind, an acceptance of her status, not among the righteous ‘chosen’ of the elect, but among the reprobates – among the damned. Here, at this high place, her very own heart of darkness where below her the landscape ‘lay in shadow’, she decided to unleash upon her readers the savage power of her imagination. Rather than seek expiation for her sins she decided to comit an unsparing act of revenge against a complacent society. It has been observed that the novel reads as a ‘scrap of history torn from the communion of the saints of old and flung in the face of the modern world, out of its context, to startle its dainty self-restraint’ (Harrison quoted in Marsden). Like Jonathan Swift who, in writings such as A Tale Of A Tub and A Discourse Concerning the Mechanical Operation Of The Spirit, excoriated the religious ‘enthusiasts’ of his day, she was consumed by a constant feeling of outrage fuelled by her own traumas, incited by her own demons. In the poem ‘From A Dungeon Wall In The Southern College’ (1844), a stern, judgemental voice derides various worldly vanities including Mirth, and, significantly, Love. This is a repressive voice of strict moral rectitude for which Love is ‘a demon meteor willing/ Heedless feet to crime.’

So be it, thought Emily, as reckless as a malefactor at the foot of the gallows, here is the subject of my novel; I will trace the path of this ‘demon meteor’. The story will tell a tale of ‘heedless’ crimes induced by the ‘monomania’ of forbidden, obsessive, sado-masochistic Love, through a harsh narrative laced with acerbic humour. It is no disservice to Emily to say that this literary project, including many, if not all, of her poems, was of an unashamedly therapeutic character. It was not some kind of visionary experience or spiritual revelation or ‘subjective encounter with the divine’ (Marsden) but rather an act of will, more akin to a work of exorcism. The culmination would be a mode of self-induced mind-expansion helping to overcome a fragmented psychological state and integrate multiple, self-contradictory interpretations of a warped existence. It is not surprising that we find the resulting psychic material expressed in culturally-conditioned theological, ‘symbolic’ or ‘spiritual’ terms; for its ultimate form the aesthetic outcome will usually depend upon this kind of enculturation.

The total nihilism of the novel and some poems is one strand of evidence, as is also that vein of saturnine humour verging on blasphemy. One thinks of Isabella Linton laughing at the ridiculous figure of the sanctimonious, pharisaic family servant, old Joseph, kneeling in a pool of Hindley Earnshaw’s blood and uttering incomprehensible supplications to the Almighty. In one childhood incident, the young Catherine outrages the same righteous zealot when she throws a ‘dingy’, devotional book entitled The Helmet of Salvation into a dog kennel, ‘vowing I hated a good book’. Lockwood’s nightmare of the ‘Pious Discourse’ of the ludicrous preacher Jabes Branderham entitled ‘Seventy Times Seven and the First of the Seventy First’ in the Chapel of Gimmerden Sough is clearly a satirical attack on low-church religious mania (Branderham may have been based on the prominent Methodist preacher and revivalist, Jabez Bunting, or the well-known Methodist clergyman William Grimshaw of Haworth, or both). The sermon descends into chaos and violence. Elsewhere in the novel there are moments of macabre, almost absurd, knockabout, as when Hindley threatens to murder Nelly Dean by ramming a carving knife down her throat: ‘“But I don’t like the carving knife, Mr Hindley,” I answered, “It has been used for cutting red herrings – I’d rather be shot if you please”’.

Surely Catherine Earnshaw speaks for our author when she appears to reject the possibility of redemption. Appearing to commit The Unpardonable Sin, ‘the sin that no Christian need pardon’, she even rejects Heaven itself: “There is nothing” cried she, “…heaven did not seem to be my home; and I broke my heart with weeping to come back to earth; and the angels were so angry that they flung me out, into the middle of the heath on the top of Wuthering Heights…”.

Unsurprisingly these defiant and desperate sentiments are echoed by Heathcliff (a symbolic figure bearing some resemblance to Milton’s Satan), when he claims: ‘I have nearly attained my heaven; and that of others is altogether unvalued and unwanted by me!’ Perhaps the most shocking character in a gallery of grotesques, Heathcliff embodies the dark power of Emily’s ‘rebellious imagination’ (Miller) her ‘revolutionary’ imagination and dreams (Bataille), and, as Charlotte Bronte wrote in her Preface to the 1850 Edition: ‘Heathcliff, indeed, stands unredeemed; never once swerving in his arrow-straight course to perdition…’

Perdition? Does Emily Bronte care about Perdition?

One feels that she summoned her own ‘radiant angel’, her Imagination, as a counter-force to lifelong threats of Perdition and Damnation from sundry authorities, Methodists, Calvinists and conventional others. The default of God envelopes Wuthering Heights in that ‘great darkness’ of the world’s night, but Emily Jane Bronte persevered to shun ‘the common paths that others run’, she ‘cast the world away’. Remaining recalcitrant to the very last, refusing all medical treatment in her final days and hours, she bequeathed to us one of the most disturbing works of English literature.

When Andre Breton said in The Manifesto of Surrealism ‘Beloved imagination, what I most like in you is your unsparing quality’ he was placing the imaginative faculty at the centre of the surrealist adventure. For Emily Bronte, whose works exemplified the ‘unsparing quality’ of an uncompromising assault on Victorian complacency, the imagination was hyper-real, not an avenue of escape. It disclosed a ‘world within’, a dangerous, forbidden, uncharted realm, ‘Where thou and I, and Liberty/Have undisputed sovereignty’.

A.C. Evans

Bibliography

Bataille, Georges, Literature and Evil (trans Hamilton), Calder & Boyars, 1973

Bataille, Georges, Preface to Madame Edwarda (trans Wainhouse), Penguin Books, 2012

Bataille, Georges, The Absence of Myth. Writings on Surrealism (trans Richarson), Verso, 2006

Breton, Andre, Anthology of Black Humour (trans Polizzotti), Telegram, 2009

Breton, Andre, Lightning Rod (1939), Telegram, 2009

Breton, Andre, Manifestoes of Surrealism (trans Seaver/Lane), University of Michigan, 2007

Bronte, Charlotte, Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell (1850), Penguin Books, 2003

Bronte, Charlotte, Preface to the New Edition of Wuthering Heights (1850), Penguin Books, 2003

Bronte, Charlotte, Prefatory Note to Selections from Poems by Ellis Bell, Oxford University Press, 2009

Bronte, Charlotte, Selected Letters 1832-1855, Oxford University Press, 2010

Bronte, Emily, The Complete Poems 1836-1848, Penguin Books, 1992

Bronte, Emily, Wuthering Heights, Penguin Books, 2003

Bronte, Emily, Wuthering Heights, Oxford University Press, 2009

Freud, Sigmund, An Outline of Psychoanalysis (trans Ragg-Kirkby), Penguin, 2003

Gray, Richard, Introduction to Poe: Complete Poems and Selected Essays (1993), J M Dent, 1999

Jackson, Rosemary, Fantasy, The Literature of Subversion, Methuen, 1981

MacEwan, Helen, The Brontes in Brussels, Peter Owen, 2014

Marsden, Simon, Emily Bronte and the Religious Imagination, Bloomsbury, 2015

Miller, Lucasta, Preface to Wuthering Heights (2003), Penguin Books, 2003

Miller, Lucasta, The Bronte Myth, Vintage, 2002

Nestor, Pauline, Introduction to Wuthering Heights (1995), Penguin Books, 2003

Poe, Edgar Allan, Complete Poems and Selected Essays, J M Dent, 1999

Polizzotti, Mark, Laughter In The Dark (1996), Telegram, 2009

Swift, Jonathan, A Tale Of A Tub And Other Works, Oxford University Press, 1999

Ward, Mary Augusta, Introduction to Wuthering Heights, Smith & Elder, 1900

Weber, Max, The Protestant Ethic And The Spirit of Capitalism, (trans Kalberg), Oxford University Press, 2009