‘And the checkout girls sing a song for the world

That goes round and round’

– Ricky Ross

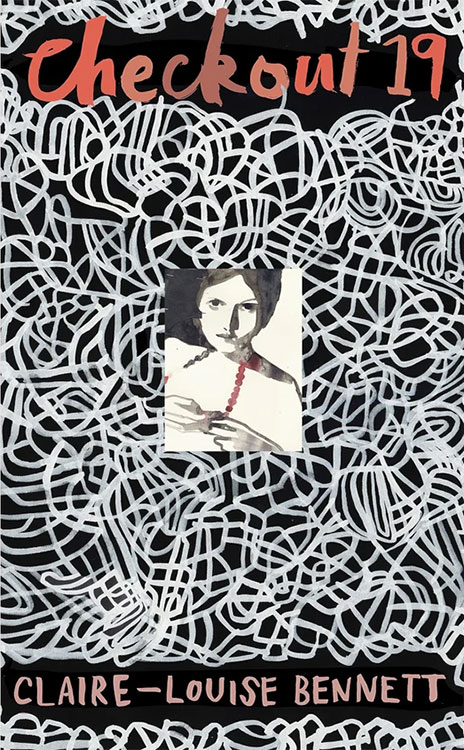

Checkout 19, Claire-Louise Bennett (Jonathan Cape)

Textual Non Sense, Robert Crawford (Beyond Criticism Editions / Boiler House Press)

A Shaken Bible, Steve Hanson (Beyond Criticism Editions / Boiler House Press)

Claire-Louise Bennett’s first book, Pond, was a collection of short stories about the lives of women in Ireland. It was careful, considered and paid attention to the everyday and mundane, making them and her characters’ thoughts the focus of the book. You could – indeed I did – read it as a discontinuous novel, which is exactly what Checkout 19 is.

Bennett’s new book is a meandering walk through her narrator’s mind: she leapfrogs associatively from the present to the past, from detail to concept, from here to there, and occasionally back again. Sometimes it is obsessive writing, with a topic being picked apart for several pages; in other places it is almost slapstick memoir, particularly some of the crushes and bad behaviour remembered from school. When she wants, Bennett can be downright hilarious, but mostly she is droll and considered.

The novel as interior monologue is hardly new, but Checkout 19 offers something different, and is a long way from the modernist experiment of, say, James Joyce or William Faulkner. Despite the way the book leapfrogs along, Bennett’s prose is polished and pared back, even when fixated on a memory or topic for several pages. It is also self-aware, and as much about reading and the act of writing, of being a writer in the world, as a story (or collection of stories). It is clever, readable and innovative.

Boiler House Press have started a new imprint, Beyond Criticism, to engage with ‘radical new forms that literary criticism might take in the 21st century’. All well and good if, like many readers and lecturers, you question the idea that criticism should mostly consist of quoting quotes from others who have quoted other quotes… And if you are questioning the notion of literary criticism, it’s just the name given to understanding and thinking about literature – which is pretty much anything these days, from radio script to graphic novel to poetry to blogs. In a world where we have had over a century of formal and informal experimental literature, where the idea of the canon has mostly been abandoned, high and low culture have merged, and the digital has replaced the analogue, surely there must be new ways to critique and write about stuff?

Well, there are. Remixology has given us a theoretical basis for collage, juxtaposition and sampling; and has been seen by some as a basis for questioning the so-called ‘crime’ of plagiarism. The arts and sciences have found new ways to relate to each other, for instance with the biological structure of the rhizome offering a way of thinking about the world in a non-hierarchical way. And, of course, colonial and post-colonial studies have trickled down from academia into the real world and helped raise questions about history, and even the statues and road names around us.

Robert Crawford wants more humour in critical writing, and also wants to see less divide between critical and creative writing. I’m in total agreement: literary criticism has yet to actually find innovative ways to deal with innovative writing, and despite the fact that good critical writing does not have to be pretentious, awkward or mannered, much of it is. The introduction of some humour might be welcome.

Unfortunately, Crawford’s Textual Non Sense is more like a schoolboy snigger than a serious attempt to subvert lit crit. It’s not often I get to the end of a book and think ‘I could write that’ but I did after the thirty minutes it took to read. Yes, it produces some laughs, and I enjoyed some of the asides, puns and subversions, but really it belongs in a cheap pamphlet, not a paperback from the University of East Anglia. It’s the sort of thing writers conjure up in the pub together, usually (and thankfully) with little follow through. The latter half of the book takes potshots at the research culture which governments (of all sorts) have instigated as a way of policing academia and reducing funding for arts subjects, but it’s an easy target and won’t convince anyone who thinks otherwise. (They won’t read Crawford’s book anyway.)

Steve Hanson’s A Shaken Bible, in the same series, is an interesting work that juxtaposes the Authorized Bible with Ranter and other dissenting texts to question belief, religion and society. Unfortunately, instead of simply letting the texts do the work he felt compelled to not only rewrite – taking out any references to god – but also ‘translate’ it into Yorkshire dialect, wanting to make a contemporary text for what another academic has called ‘the broken middle’, a term which feels as outdated and useless as ‘everyman’. Whilst I admire anything that questions what is given and subsumed by authority, and that is interested in how society works, I can’t but feel that Hanson has merely muddled things and denied himself a possible wider readership.

I’m a big fan of collage and juxtaposition as a form of criticism, and am not worried about texts being ‘difficult’, but I think novels such as A Clockwork Orange and Riddley Walker have done a much better job of questioning social norms and political structures in new languages. The latter, especially, questions and critiques myths and rituals, with its post-apocalypse creation story that mixes up St Eustace, nuclear fission and Punch & Judy, all told in a broken and deformed English by surviving tribes in what was once Kent. And of course, there are plenty of other theological, a-theological, pagan and dissenting works that rework the Bible and other ‘sacred’ and political texts.

In the end, the clarity and precision of Bennett’s storytelling offers much more of a critique and questioning of creative writing than Hanson’s and Crawford’s books do. Checkout 19 gets the reader questioning when fiction becomes non-fiction, how digression and asides function as the focus of writing, and how literary asides and allusions to other authors and books might be useful and creative. Crawford and Hanson may talk about a place where critical and creative writing meet, but in the end they have retreated into respective (book) corners of silliness and obscurity.

Rupert Loydell