On the publication of the 25th anniversary edition of David McGillivray’s Doing Rude Things

(Wolfbait Books/Korero Press, 2017)

Second only to the Kama Sutra (as we can cast Gideon’s Bible safely aside), David McGillivray’s DOING RUDE THINGS is a testament to what the lonely and abandoned reader can do with one hand, as well as being a significant literary landmark in the history of sex. Or rather, in the history of British sex, as the book is a masterly account of the British Sex Film from soup to, as it were, nuts.

This elegant and, it has to be said, voluptuous reprinting by Wolfbait Books an imprint of Korero Press, marks the book’s twenty fifth anniversary, for which it has been greatly revised, updated and expanded. It tells the stories behind the sex films made in this country in a once golden if slightly chipped age, along with the fates and histories of those responsible for them. These pioneers and libertines of the pre and postwar years, from the sexually sainted Pamela Green and somewhat less savoury Harrison Marks, through to today’s burgeoning underground are revealed in all of their effete and grubby glory, from the sepia stained windows of the 1930’s, through to McGillivrays recent production of the short film, Trouser Bar, currently unzipping across the world’s film festivals, written and suppressed by a former Knight of the realm and his somewhat embarrassed estate.

In six concise and beautifully mounted and illustrated chapters (Pioneers, Legends, Grafters, Final Days, Aftermath and Renaissance), and a lengthy end section of biogs and summaries, McGillivray details Britain’s obsession with its sexual identity, showing how it has struggled to reveal itself by both fair means and foul, smuggling in visual and textual references as far back as the days of silent film production, with greater disclosures appearing in the early films of Will Hay, George Formby and a woman flanked Arthur Askey, blissfully menaging away in an underground tube station during the blitz. He forges the links between the freedom and restrictions of the Georgian and Victorian eras, and shows that while the love of sensation that runs through the English psyche is perhaps not as pronounced as the French joie de vivre, it nevertheless shakes the English skeleton, made as it is of garish and cheap Brighton rock.

The formulation of film censorship and the creation of the notorious X certificate in 1951 provided the first gate those seeking thrill and titillation needed to pass through, and seven years of fleshly famine later the first nudist film glazed the screen. While primarily concerned with the throwing and catching of beach balls, these sexless escapades soon saw other objects of joy being handled and shown to the air. What McGillivray charts is an almost princely procession/progression from the relative innocence of these pictures to the more lurid tales still to come. People could birdwatch in Soho at the infamous Windmill club, but only if they liked their tits static. If it was movement they wanted they would have to move further afield.

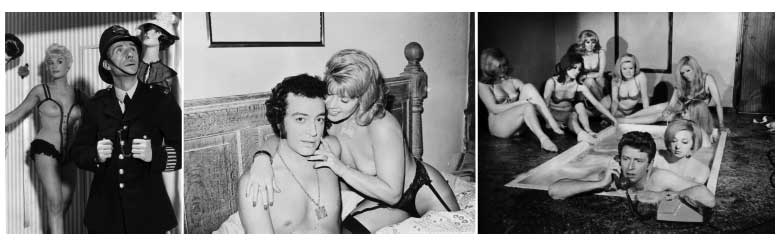

Pamela Green, who wrote a spirited introduction to the first edition in 1992 (included here along with revised and new introductions by David McG.) was the real sex films pioneer in this country and apart from McGillivray himself, the sex market’s greatest provider and trader. Although it was Harrison Marks who made the films, she was the star and later producer, as important to the British way with sex as Bardot was across all manner of waters. Her cool, almost Scandinavian features set the template for the sex star that has more or less endured until now. In her wake, scores of models, chancers and actresses followed, sucked into the thrall of Marks and contemporaries of his like Derek Ford, whose career in filth ended on the suitably shabby floor of the Bromley Branch of WH Smiths towards the end of the last century. Many of these women have been forgotten, passing before our squinting eyes in appearances in Carry On Films and the Confessions series before settling into Grandmotherdom in any number of neglected resorts. One or two became leading British actresses, sit com stars and courtesans of film cults everywhere, but most struggled to either survive or put their slightly stumbling first steps behind them. In McGillivray’s elegant pages, precise and witty prose and spotless research, he documents how these films, many of them the product of varying degrees of desperation, still helped set a standard for the kind of entertainment people yearned for as easy release.

Although a fervent modernista and follower of the new, McGillivray (not overly given to sentiment) yearns a little too, I think for the shabby colour of those bygone days and the colourful people he knew and quite often worked with as screenwriter and actor. Troublesome and prematurely retired Film maker Pete Walker features heavily, the former king of british exploitation, probably because he was able to fuse Britains true contributions to cinematic culture, sex and horror, seamlessly. Other practitioners do not fare quite as well, but McGillivray patterns them all in, lovingly. As one of the last but still working survivors of that scene and time, he has proved the most adaptable. Some of the figures mapped and charted here have become less than rumours, but McGillivray has time for them all and must be the only man alive who has used his hours searching for a still missing obituary for Peter Austen–Hunt, the film editor of White Cargo and I Like Birds,among others. From Ray Selfe, Pat Astley, Marie Devereaux, and onto Prudence Drage, Sue Bond and Howard Nelson, they are all here; Britain’s fallen idols of sex and sin, already half submerged at the time of their emergence they nevertheless cavorted and moved through the tatty rooms and anorexic budgets that housed them to present a horny public with the cheery arousals half of them never knew they needed. Doing Rude Things is all we ever truly aspire to in this country of ours/theirs, and this seminal, semen threatening volume scratches at the English reserve wonderfully.

From the almost exotic, near Chinese appeal of Barry Evans to Lynda Hayden’s highly sexualised eyebrows. From Harrison Marks’ eerie predilection for false noses and comedy toupees to the mud wrestling of Strand Films Stag Show Girls, all are here and upstanding, like the ghosts of forgotten shags who have forgotten to leave the chamber. As McGillivray inspects his parade, Julie Ege lets things slip and Pat Wynn’s enormous breasts jiggle. Michael Armstrong is writing but there is no film in the can. Fiona Richmond reclines as someone fellates Linsey Honey. Jim Dale’s eyes are bulging as Robin Askwith’s arse dares us all.

Showing or hiding the clear point of entry was a censor’s term used to define the differences between soft and hardcore pornography. Many of the films alluded to in this book were made with different sets of cameras placed to reflect (and indeed capture these variations) and the notion of nasty scenes involving Bob Todd and Joanna Lumley seems almost irresistible. But it is important to document here that this book is no litany of societal evil. It is in fact a kind of Soho Babylon that never quite leaves the bus or airport. Sex and later, horror films were the easiest ways for young film makers to start their careers and this was the case for artists like Norman J Warren and to an extent, Michael Reeves. The humour and misadventure of some of these enterprises is something that McGillivray also captures, even if at times he is directing our laughter towards the varying levels of misfortune and ineptitude on display. His updates leave his own contemporaries behind to take in the production of recent forays into the genre, such as Carry On, Columbus, Sex Lives of the Potato Men and Lesbian Vampire Killers, and while offering kindly reviews he shows that what signalled the end of these films was a lack of heart, opportunity and dare we say it, soul, if tenures of varying sorts were needlessly extended. As short, sharp comings, eruptions and goings, the tumescence of excitement is maintained. Linger too long and these nefarious shadows will stain you, as they did for Marks, Margaret Nolan and Mary Millington’s sad decline.

It was also Thatcher as well, slashing away at expression and the restrictions placed in the eighties that marked the end of these films. That she becomes a kind of censorial Freddie Kruger or Politicised Puritan, as lascivious in her need for domination as any leering pederast featured in shabby raincoat on a darkening afternoon, is not a fact lost on McGillivray. He trains a steely eye on the industry and society he has moved through for fifty years and at a still sprightly time and age the republication of this book marks a form of personal renaissance for him. New films, scripts, pantos and copy emerge at an alarming rate, as he adds to a comprehensive study of the limits and extremes of the country’s tolerance. Of course, you can’t really have a renaissance for someone who has never truly gone away, but it is very good, nay propitious to have him out there and this book reminds us that a singular view, formed from the wryest of humours and the sharpest of intelligences challenges the norm and shows us all just what is missing from current practise. We have moved away from the strong statement, reaching a point where we rarely understand our own desires. This book manages to be both a memorial and celebration of other wasted talents, captured by one that is as active as it ever was.

These were firework films, and Doing Rude Things re-ignites them. It is a brave and beautiful volume in which the filthy and fucked attain grace.

David Erdos, 17/10/17

Doing Rude Things is available from www.koreropress.com or Amazon at http://amzn.to/2xR0WjU