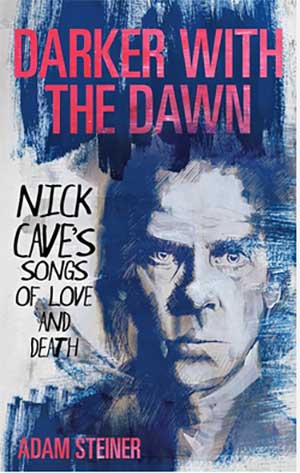

Darker With the Dawn: Nick Cave’s Songs of Love and Death, Adam Steiner

(327pp, Rowman & Littlefield)

Nick Cave was never truly on my radar until lockdown. I knew who he was, of course, and his Kicking Against the Pricks album of cover versions was tucked into my record collection, mostly because of his angst-ridden interpretation of The Seekers’ ‘The Carnival Is Over’, which my mother played endlessly during my childhood, managing to earworm it into my head and then force me to finally admit, decades later, that I liked it. But I had never heard The Birthday Party, The Bad Seeds or any other Cave solo albums.

Then lockdown arrived and we all scrabbled to find things to keep us occupied. I’m not a big television watcher, but in July 2020 Cave’s film Idiot Prayer was streamed and I was entranced as Cave sat alone at his piano in an empty hall, playing and singing his heart out. Mojo‘s reviewer suggested that the album version released later that year was ‘extraordinary, breathtakingly varied […] and compelling throughout.’ I’m normally wary of the confessional or seemingly confessional, let alone any notion of ‘truth’ in the marketing or work of singer-songwriters, but I was intrigued enough to buy some of Cave’s other albums and also Faith, Hope and Carnage, a book of conversation and discussion between Cave and journalist Sean O’Hagan, which explores grief, spirituality, creativity and what journalist Rachel Clarke called ‘the inscrutable alchemy of songwriting’.

Whilst Cave suggests to O’Hagan that he engages in a ‘struggle with the notion of the divine which is at the heart of my creativity’, elsewhere he has also stated that his songs are asking for ‘forgiveness from God’ and that for him

To make art and do things creatively is a way of redressing the balance

of our sins in the world. That’s one way to do it. To make art and to

write songs goes some way in improving matters. That songs are

fundamentally good. There’s a sort of moral dimension to a song that

they do good. They make things better. And I think that’s one way of

making amends or reconciling oneself to the world. (Gray 2022)

Adam Steiner prefers to consider faith (and doubt) more as a framing device or source of inspiration than a given for Nick Cave. He suggests that Cave’s church upbringing resulted in ‘The Bible [becoming] a space of creative antagonism’ and that ‘[w]ith or without the absolutism of ritualized belief Cave found something there’, yet concedes that Cave would later fall ‘in love again with the language of the heart and the noble idea that spiritual goodness is possible in everyone’ and embrace ‘the abiding power of faith, but [turn] this inward as creative inspiration to practice his own version of faith without Christian dogma.’

Steiner is good at discussing Cave’s storytelling, citing the influence of Flannery O’Connor on his ‘powerful hold of the sacred and profane’ and noting that in Cave’s love and relationship songs this often includes

the extremes of physical attraction—the grounding force of lust and

desire driven into sex. He strides in and out of high-flying romance to

carnal excess—the spark that leaps between emotion and flesh—just

as easily turning from sensation to an emotional car crash.

(Steiner 2023: 28)

Cave’s songs can evoke ‘sexual need as a show of brute force’, whilst also considering a ‘love affair as an elegiac adventure’, ‘often illuminated in terms of high romanticism, where love becomes an all-consuming emotion that turns back on itself towards destructive tendencies on an apocalyptic scale.’ This excess is typical of Cave’s work, perhaps of Cave in person, but Steiner keeps an authorial distance from the songwriter and focusses on the work, although it is at times difficult to separate Cave from the narrators of his songs, especially as he seems to have recently committed to blurring those distinctions and embracing an idea that Steiner expounds as ‘find[ing] something from nothing that suddenly comes to mean everything.’

However, Cave is no mystic waiting for his muse. Steiner notes that

Cave would stress the work done behind songwriting, explaining: ‘I also

have an affinity with artists who treat their craft as a job and are not

dependent on the vagaries of inspiration—because I am one of them.

Like most people with a job, we just go to work.’

Whatever Cave has recently said about himself being very present in recent albums and published writings, he has always been and remains a performer. Steiner states that ‘Cave has always worked to inflame and subvert the melancholy pessimism of his public image’, suggesting that ‘[h]is deft and determined approach is to shock us out of normality’. Cave is, declares Steiner, ‘100 percent sincerely inauthentic; depth of feeling met with artistic construct’.

By considering this construct, and using plenty of intelligently used and well-referenced source material, Steiner is able to discuss the ideas and creative texts Cave draws upon for his songs: ‘early notebooks; half scrawled with song lyrics and bloody junk-sick grafitti’ that also contain ‘pasted-in icons of saints and pornographic postcards’; ‘shifts between the poles of John Betjeman’s suburban verse, Larkin’s bitter but sensitive poetry, and Emily Dickinson’s use of dashes as punctuation, while alluding to e. e. cummings’ use of ellipsis and enjambment’; Kanye West, Elvis Presley, Iggy Pop, Mark E. Smith, Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen, Shane McGowan, and Johnny Cash.

If at one time, due to addiction and Cave’s wild lifestyle, there was ‘a highwire divide between stand-up performance and laughter at the funeral party, [with] Cave’s songs demand[ing] that above all we are able to laugh at ourselves’, it may be that Cave’s current religious obsessions are another kind of drug: different to heroin but also able to numb the pain of grief for his son’s death, and perhaps one that still allows Cave’s life to be ‘chaotic and confused and destructive’, a state that he says allows him ‘to fill up with a lot of ideas.’ These ideas include the notion of ‘an inchoate view of God’s presence’ and the adoption of ‘a free-range Christianity that allows people to wander’, which Steiner considers in the light of Sylvia Plath’s unanswered speech to God, and Soren Kierkegaard’s ‘leap of faith’, where ‘trust[ing] in faith itself’ is enough..

Zoe Alderton, in a perceptive article in Literature & Aesthetics, seems to concur with Steiner’s interpretation, suggesting that

Cave’s amoral view of God has permitted an overt use of violence and

romantic love as spiritual elevation from mediocrity. He does not view the

insanity of spiritual belief as a negative manifestation. Rather, he engages

with madness as the birthplace of the true love song and as the egotistical

lunacy of violence and its striking linguistic quality.

Steiner concludes his book by suggesting that ‘the opportunity of life gives us the chance to experience and create great things in works of art and acts of love and kindness.’ Alderton also ends on a similar theme, noting that ‘[f]or Cave, divinity can be found in language and creativity’. I don’t want to suggest Steiner’s study of Nick Cave is divine or even divinely inspired, but it is engaging, erudite, and highly readable as it its critiques and discusses Cave’s music and lyrics, their inspirations and possible meanings, whilst sidestepping the musical and biographical chaos that Cave once caused, as well as the religious confusion he has currently embraced. Steiner is an astute, imaginative and optimistic writer, and this is a fantastic book about the work of Nick Cave.

Rupert Loydell

.