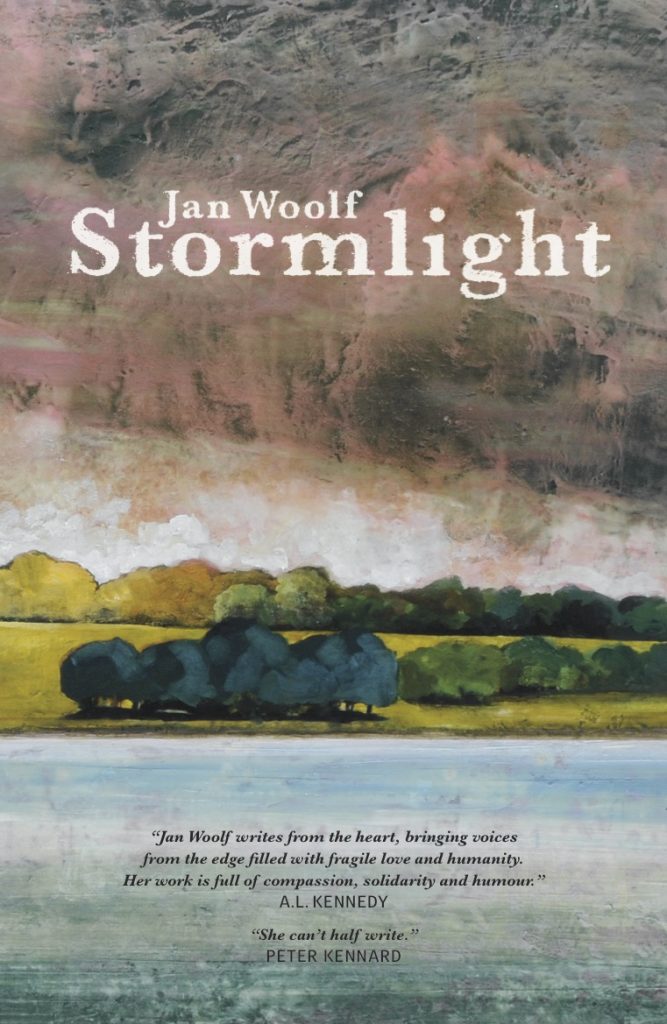

Jan Woolf’s book of shorts Stormlight was launched just before lockdown at Housmans Books, with all subsequent readings cancelled. Her publisher Riversmeet, is organising another (on zoom, not in a room) this autumn. Watch this space. Stormlight (signed) is on sale from http://janwoolf.com and keep an eye on https://riversmeetproductions.co.uk for the other wonderful things they do. Not least an up coming course on Ulysses. Meanwhile here is a taster from the collection.

Cultural Studies by Jan Woolf

Elly stirs in her hangover. The china foal she gave her Aunt shimmers into focus on the bedside cabinet, beside the digital clock telling her it’s 7.32. She jack-knifes her knees to meet the ache in her heart. She’d longed to wake up with him this morning, yawning – their limbs entwined. She wants to cry, but he’s not worth it so she throws his pillow across the room instead. She recalls the conversation in the small hours.

‘It was all about the exploration of attachment honey, at least I fessed up,’ he’d said.

‘Another post grad’ student was she?’

‘He.’

‘You flake, Tyrone, you only come here with me because it’s trendy Whitstable.’

‘No, it’s because I want to be with you, Elly.’

‘Attachment, my arse.’

‘Please don’t be bitter.’

‘One for sorrow, two for joy?’

‘Eh?’

‘That’s what you say when you see a magpie on its own, Professor.’

‘A what?’

‘Magpie – black and white bird.’

‘I know, I’m not stupid.’

‘When you see one on its own it means sorrow.’

‘And two is for joy?’

‘Yes, but it’s meant to mean us, not….’

‘Referencing wildlife – of course – forgot – you’re a country girl.’

At least he hadn’t accused her of rural idiocy, like before.

‘You meant to call me a rural idiot didn’t you?’

‘Of course not, sweetie.’

‘Idiocy is Ancient Greek for obsessive pre-occupation with self, did you know that?’

‘Nope.’

There was a lot he didn’t know. The idiot.

‘I never want to see your postmodern arse again. Go fuck a brick.’ And he left Aunt’s B&B, and walked away into the night. There were no trains, so he probably spent the night in a beach hut.

She turns in the apricot nylon sheets, wondering if the sparks are her agony, or the reaction with the synthetic fabric of the nightie she’d found under the pillow (that had turned him on). Ends were wretched, especially after the first romantic months; the Brick Lane curries, dirty weekends, the art galleries.

Last week, in the National Gallery she’d shown him the tiny smears of red that Corot had put in each of his whispering green-grey landscapes, telling him that this was each work’s centre, ‘to draw in the eye, like an infant’s to a nipple.’

He’d liked that.

She thinks back to their beginning. He’d given her final dissertation on The Communard Courbet a 2-1, inviting her to lunch to discuss the gender implications of the Paris Commune. The rest had been history or ‘the end of history’, he’d quipped, stroking the back of her hand with his long white fingers.

Clever Tyrone. The only lecturer in the Cultural Studies department to wear Converse trainers with a suit. Wore his learning well too. His PhD, Aesthetics in Post Industrial Society had been translated into eight languages – even Albanian. Sexy Tyrone; handsome and tactile, with mooncalf eyes and dark all day stubble. Not just a pretty academic either, his novel Working Title had been well received and he was getting guest spots on Culture Vultures.

And he was divorced,

And he was good in bed.

‘Quite a catch,’ she tells the china foal.

She stares at the wallpapers of mottled mauve and regency stripes, and the picture of a Victorian girl child in a white dress standing on tiptoe, her mother’s receiving arms just visible inside the golden plastic frame, and she wants to weep. The picture isn’t hung, but screwed to the wall. Tyrone had called it an installation. ‘Oh Tyrone, you were so funny sometimes.’ She wants to grizzle into the polyester pillow, but she knows it wouldn’t soak up the tears – if she had any.

The last time they were here he’d made an action, as the Fluxists would have put it. ‘Let’s make some real shit,’ he’d sneered, eyeing up the china foal, tearing up pieces of his Lib Lit Supplement, spitting into them, pudging tiny pellets of newsprint in his fingers, then placing them in a row behind the foal’s straddled back legs. It was the first time she’d seen him actually make anything, other than his roll ups. Feeling mild guilt at the collusion, or collaboration, she’d re-arranged the tiny turds into the more authentic heap that would lie beneath a horse.

‘Don’t they shit while they’re walking along?’ he’d asked.

‘No, and I gave that china foal to Aunt for Christmas when I was six.’

‘Foal? I thought it was a pony.’

‘No. Ponies are small horses. They have foals too.’

‘Wouldn’t that make them poles?’

‘Shut up.’

‘Do you like all this kitsch, honey?’

‘It’s my aunt’s’.

‘That’s not an answer.’

Well, it was answer enough for her, and if he didn’t get it? OK. He got Derrida, Foucault and Lacan, so maybe they could explain.

Then he’d turned aunt’s reproduction of The Haywain upside down.

‘Why did you do that?’

‘To help her see afresh….’

‘You mean my aunt.’

‘Yes, the balance of the composition, and question the reality of her own existence.’

She’d laughed, imagining the man falling out of his cart and tumbling into the sky. ‘Constable would have found that funny, wouldn’t he Hon’?’

‘Who? Oh – cuntstable. First time some guy had ever painted clouds, big deal.’

She’d turned away from him then. Yes, the first time some guy had painted clouds.

‘What did you call him?’

‘Kunstable, sweetheart. German for art, with a stable attached.’

She sits up in bed and looks at the upside down Haywain, the man clinging on in his cart, timeless, safe as houses. Aunt can’t have noticed. She feels guilt at the collusion, implying that her aunt was a fool, and wants to cry again. But he isn’t worth it.

The Kunst.

She looks at the sunlight straining through curtains of brown and orange flowers. Tyrone had loved those curtains – the whole room in fact; ‘its context and signifiers.’ He’d once suggested flogging them at Spitalfields market, so that her Aunt could afford some nice white slatted shutters with blinds, more in keeping with the contemporary Whitstable feel. ‘This junk will be worth a fortune one day,’ he’d said, while pissing in the sink.

’You can’t do that, Tyrone.’

‘Why not? It’s sterile.’

‘The sink?’

‘Piss.’

And so was he.

There’s a tap at the door. It must be 8 o’clock. She looks at the clock. It is.

‘Come in, Aunty.’

A waft of eau de Freesia and fried food accompanies her Aunt, whose rump is the first thing in the room as she balances a tea tray. As she turns, it’s all held before her like a ship’s figurehead; teapot, milk-jug, sugar bowl, plate of biscuits, two cups and saucers. Under the hennaed hair, she sees an older version of her mother’s face and wants to cry. ‘Hello Aunt.’

‘Morning Lovey, where’s that Teroll then?’

‘Tyrone.’

‘Yes, him.’

Elly, spotting the extra cup starts to cry.

‘Oh dear,’ says Aunt, setting the tray down, sitting on the side of the bed, pulling her niece towards her. ‘I quite like the picture like that you know,’ she says, patting the huge infant crying on her shoulder.

‘What picture?’

‘The one by the man who painted Constable’s Haywain, you can see the cloud effects better, the bushy trees, and the shine on the water and the horse’s bottom.’

‘Tyrone did it.’

‘I know. That’s why I left it like that. Daft bugger.’