Blank Canvas. Art School Creativity from Punk to New Wave, Simon Strange

(297pp, Intellect)

Whilst being fairly enjoyable reading, this is a backwards kind of book, that tends to see links, connections and inspirations after the event, many of which are not the slightest bit convincing. It feels very ‘researched’ rather than lived, which I guess is how academia often works.

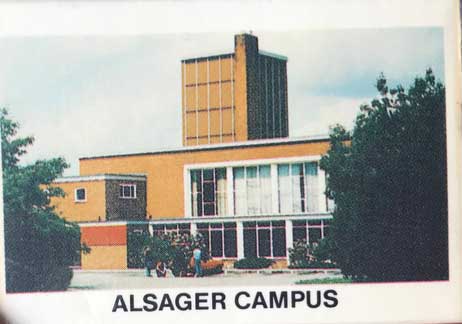

One of the main problems is it just doesn’t seem to be what I and others experienced at college during the time Doctor Strange writes about. Crewe & Alsager College’s Creative Arts degree had five strands running through it (music, writing, visual art, theatre and dance) and students initially took two of these, which could be sustained or reduced to one as students wished. But all five subject area students were one cohort, meeting together for lectures and practical projects under the title of ‘Integrated Arts’ in addition to our own studio practice, performances and workshops.

This meant, for instance that, despite being a painter and writer, I could use the music studio to record my band’s music, the reprographics department to print posters and zines, and contribute sound and lighting to my partner’s and her friends’ dance performances. Our tutors were a lively mix of practitioners, theoretical lecturers and one escapee painter from Ealing, who preferred the Cheshire quiet to dealing with other artists such as Gustav Metzger and Harold Cohen, the telematic Roy Ascott, or students like future rock star Pete Townshend. There was also a Crafts degree on campus, whose students we mingled with, despite there being a very different ethos to their course; and the obligatory sports students who usually drank somewhere else then came back to the campus bar for last orders and a fight. (We did once work out we had a good rugby seven on the arts degree who had played for county or colts teams, and talked about challenging them to a match.)

It wasn’t just about our own degree though. I never again saw so much experimental theatre, music or new dance as I did in the early 1980s. Alsager College itself was on the performance circuit back then, and Manchester, Chester, Liverpool, Stoke on Trent and Keele University were all within striking distance for other events. One favourite evening of mine was at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester where we saw Mantis Dance, Ivor Cutler and Psychic TV, although Cutler was because we snuck in at the interval to another performance space when Psychic TV decided they didn’t want to start playing ’til late. (The band were apparently sulking because Kathy Acker had left the tour at very short notice, calling Genesis P-Orridge all sorts of names as she did so.)

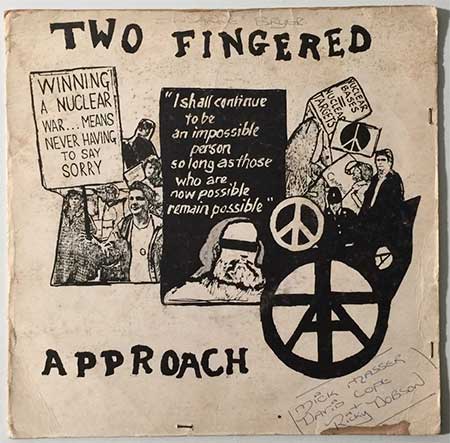

Crewe itself was full of punk and postpunk bands, such as Two-Fingered Approach (who had already released a single, ‘My World War Album’), Corpse, Flowers in the Dustbin (who were convinced Flux of Pink Indians had stolen their experimental ideas from a demo tape they had submitted to them) and John Everall (who went on to form Sentrax Records but at the time recorded work under a bewildering series of pseudonyms and one-off band names). All were plugged into the DIY cassette culture of the time, establishing support networks around the country that facilitated touring, tape exchange or sales, and spreading the anarchist word.

Whilst I can’t prove that what I experienced at Crewe & Alsager was the norm, the above is somewhat at odds with Strange’s thesis that punk and new wave music emerged from, and in resistance to, art schools undergoing a shift away from unregulated experiment and adventure to more managed, theoretical and conceptual hierarchies. Maybe this was true in London (though it wasn’t at my Art Foundation course in Twickenham during 1977-78) but nothing was as clear cut as Strange suggests. In fact my general impression of this book – apart from the fact it needs a good copy edit to get rid of, for example, lots of repetition such as ‘for example’ – is that it is a tidied-up version of things, trying to establish a linear history when the reality was messy, fragmented, chaotic and geographically varied and specific.

Yes, there are labels we apply, for ease of use and marketing, to genres, theories and fashions, but the reality is that even as the Sex Pistols and their entourage hogged the news for a bit, groups like This Heat and the Flying Lizards were producing deconstructed rock music, and the charts were still full of disco and novelty hits. We know by now that little happens in isolation: New York produced disco, punk and hip-hop in the same few years, with people like Arthur Russell playing with Philip Glass and Talking Heads in addition to recording his own gay disco anthems and multi-tracked cello experiments. And consider how the New York punk label managed to be applied to such different bands as Television, Patti Smith, Blondie, The Ramones and Talking Heads, none of whom had much in common with the Sex Pistols, Clash or Siouxsie & The Banshees over in the UK.

Yes, cybernetics, conceptual art, abstract-expressionism, performance art, action painting and auto-destructive art were part of art schools, just as figure drawing, colour theory, design, typography and print skills were. And, yes, different pedagogies arose or were imposed, and universities became (and remain) more accountable to councils, governments and the education establishment. And yes, I’m sure that musicians who happened to be at art school took on board some of the art-making processes or critical and theoretical ideas shared with them, but I imagine just as important were the debates and arguments during tutorial and class feedback sessions and studio visits, seeing and hearing about what other students were doing, and endless discussions in the pub or student union bar. Not to mention the radio, gigs, borrowed albums, what NME and Sounds reviewed (Shout out to Paul Morley and John Gill) and the nearest independent record store had available. (For the record we had a fantastic one in Crewe.) But most important of all was time and space, paid for time and space for three years, and access to equipment and resources. I worked for four years before going to university, and couldn’t believe what was on offer and available if you chose to make use of it all.

For me, this is what the influences were for musicians coming out of art college. But let’s not be stupid, many art students didn’t like punk or new wave music and many punk and new wave bands never went near an art college unless they got a gig there. None of those Crewe bands I mentioned had been to university (though some members would go in due course), they simply wanted to play together, record, and share their music with a bit of rebel attitude. And technology such as 4-track TEAC recorders and cheap local studios facilitated that.

Strange’s book is intriguing, but it is head over heels. You can always find music that reflects what you want it to. So I am underwhelmed when he selects a topic such as the Situationist International, Systems Theory or Cybernetics and then finds a band to ‘evidence’ a connection; and even more underwhelmed by section headings such as ‘Attitude’ and ‘Eclecticism’. It misses out the larger picture, of what was taking and had taken place in genres such as contemporary classical, improvisation and electronic music. Yes, Cage and his book Silence gets the obligatory mention, but not much else. One of the great things about attending events at the London Musician’s Collective back in the day was the generous mix of music on offer, from minimal percussion events (metal objects laid out on a blanket being banged, rubbed or plucked) to ear-splitting group improvisation via Keith Tippett’s lyrical piano explorations, wordless vocal gymnastics, punk thrash and epic saxophone solos reliant upon cyclical breathing.

It seems to me that this hybridity and openness, aligned with the end of hippy idealism, along with a rejection of early neoliberal economics and what passed for popular music back then was what created punk. As early as January 1978, Robert Christgau, in his ‘Punk England Report’ for The Village Voice, noted that ‘Punk doesn’t want to be thought of as bohemian, because bohemians are posers. But however vexed the question of their authenticity, bohemias do serve a historical function — they nurture aesthetic sensibility.’ Now, bohemia was certainly part of the art college experience, always had been, but other bohemias were and always have been available.

My personal bohemia back then, certainly produced results. Active or would-be session musicians, composers, singers, guitarists, keyboard players, studio technicians, film and TV scriptwriters, authors, editors, publishers, performance artists, puppeteers, ceramicists, teachers, lecturers, dancers, painters, sculptors, community arts workers, costume designers, actors and administrators all graduated with me, emerged blinking into the reality of mid-1980s Britain, just as they did elsewhere. Some of us were able to do what we wanted (and still do), some of us didn’t or couldn’t, but back then all of us knew how to learn for ourselves, all of us had a critical language to engage with the arts, some technical skills, ideas, enthusiasm and ambition. It seems to me that this is neither punk nor art college specific, it is simply about the creative arts (including music), creativity, and wanting to engage with it.

Somewhat surprisingly, Strange ends his book by saying that he hopes it might ‘provide connections to support thinking within creative arts curricular’, which seems to me – after 17 years as a university lecturer – somewhat misguided, over-optimistic and naive. There will always be those who inspire, facilitate and encourage students but it will be despite the current curricular and neoliberal regimes which have turned education into yet another would-be-business. I think youth culture’s focus on music has already been swept away by the rise of games and on-demand films, not to mention fame academies and TV shows, and there certainly won’t be another movement like punk or post-punk any time soon. There will, are and always have been outposts of musical, theoretical, inspired and inspiring subversion, aggression, critique, noise and experiment, but it won’t and never has been tamed by, let alone been the direct result of, even the most liberal of art colleges.

Rupert Loydell

Robert Christgau’s ‘We Have to Deal With It: Punk England Report‘ can be found at https://www.villagevoice.com/2020/01/09/we-have-to-deal-with-it-punk-england-report-2/

Alsager was something else. The only the thing I ever found like it was at London University in Canada but their thinking was also much more traditionally linear than it had been at Alsager. Alsager was chaotic and messy and glorious and you really did feel licensed to do whatever occurred to you. Shedloads of memorable work emerged all around in the three years I spent there.That Rugby match did take place I’m reliably informed and also I was there to see the year the captain (and prop forward) of Alsager RFC starred in Bill Sinclair’s anarchic drama/happening epic in protest at the Falklands War. Integrated Arts it was called and integrated arts (and living) it was. I often considered whether it had sprung up from John Wyndham’s fictional survival community on the Isle of Wight as philosophised in DAY OF THE TRIFFIDS. That is exactly how Alsager encouraged you to think – not about reconstructing the old order but starting again and doing it better.

Comment by gary boswell on 28 January, 2023 at 10:57 amAlsager College now sadly all flattened and turned into a housing estate…….The Triffids never go away!