The Island, Robert Darch (Lido Books)

‘On Thursday 23 June 2016 the EU referendum took place and the people of the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union.’ So says the Gov.UK website, without comment or critique. It came up as the first return from an online search for the date, which is printed on the half title page of Robert Darch’s beautiful book of photographs. These two pages initially seem to be the only text, apart from some thank yous and publishing information inside the back cover, but a little more exploration reveals a prose text inside the front cover flap.

This – presumably designed as an introduction of sorts – is a moody story about the dull provincial life of an unnamed narrator, whose ‘town was about as far from anywhere as you could get, landlocked and lacking.’ It is one of many towns ‘where people’s lives were mapped out by circumstance and routine. All those people and the weight of their existence, nobody moving.’ This is contrasted with lyrics from a Fugazi song, where ‘Everybody’s moving, moving, moving, moving’ and the singer begs ‘Please don’t leave me to remain’.

Stasis is a constant throughout the text: regular visits to clubs, persistent downing of lager, constant rain, a crowded bus… but in the distance, the Malvern Hills, with a memory of camp and the view of a hidden, fogbound landscape. It is put aside as the bus trundles on, taking the narrator to college…

Perhaps I am reading too much into it, but the camp is named the British Camp, and its nostalgic allure is at odds with the desire to be moving, along with everyone else. It certainly sums up that mix of group memory of a fictional British past we are taught at school (free of colonialism, racism, abuse and violence) and the resulting xenophobia and snobbery directed against ‘others’: other countries, other races, other people, people with other ideas about how to eat, live or run their own nation.

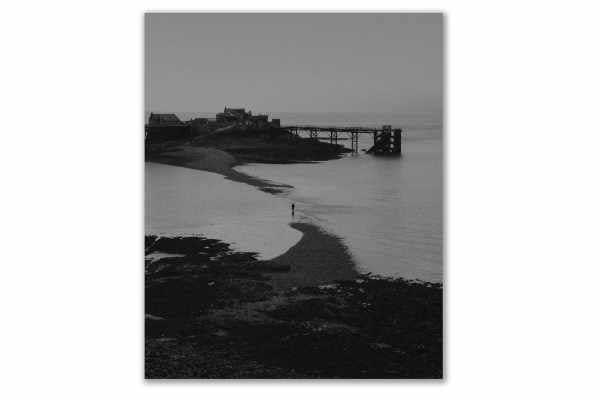

The photographs in The Island reflect all these ideas. There are alluring misty landscapes, beached boats and a local train (perhaps even running on time?) and views out to sea. Live with these works a while, pay attention, however, and the images change into something else: a land of tired and stressed individuals, abandoned mines, factories and industrial buildings, damaged and dying nature, man made intrusions at odds with the world around them.

Houses are empty and overtaken with ivy; trees are dying, stripped of their bark or with their branches brutally lopped; nameless individuals and couple stare assertively at the camera, traverse or sit in the ruins they find themselves in. That boat pulled up on the beach turns out to be abandoned, that beach chalet looks uninhabitable, and when was the last time children played on those rusty, restrung swings? Another beach chalet which appears still in use has cushions piled high in the window, and several others spilt across the decking. And why are those people standing high in a bare winter tree? What can they see? Are they moving, moving, moving or watching others move? Or have they all been left behind?

This is a dark, monochrome book; a disturbing one, too. It depicts a country isolated from its neighbours, inhabited by worried and concerned young people who have been left with the ruins of the world they grew up in. What was promised never happened, has been taken away, and they can only look out of broken windows, from windswept beaches and stormswept cliffs, imagining past freedoms and denied possibilities. Three of the photographs are particularly poignant for me: a shovel stuck in tar on a concrete floor, a woman kneeling in a field with an impressive country house behind her that she will never inhabit, and the final photo of a desecrated tree, reduced to a stump of wood in the mist. The distant light in this and other photos, even the light at the end of the mine tunnel in one photo, offer little chance of illumination or a fulfilling future.

Darch’s stark photographs offer a persuasive kind of narrative or meta-narrative about how and where we live, post-Brexit, post-covid, how we have chosen isolation and ignorance over possibility and partnership. It is a disturbing, anxious and thought-provoking book that contradicts the preposterous notion that we are a civilized, affluent and caring society. It is not, however, didactic or polemical, it is a gathering up of persuasive and visual evidence where ‘nothing of the present seem[s] familiar anymore’. We are all shipwrecked and abandoned now.

Rupert Loydell

Robert Darch is a British artist-photographer based in the South West of England. He has published and exhibited widely and his photographs reside in public and private collections. You can find out more about him and his work, as well as purchase The Island and other books, at https://www.robertdarch.com/

Portrait of Robert Darch by Tavis Amosford