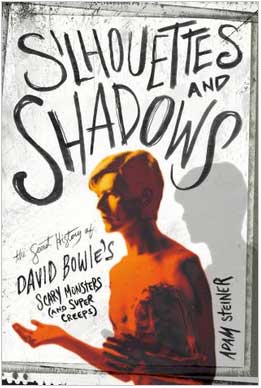

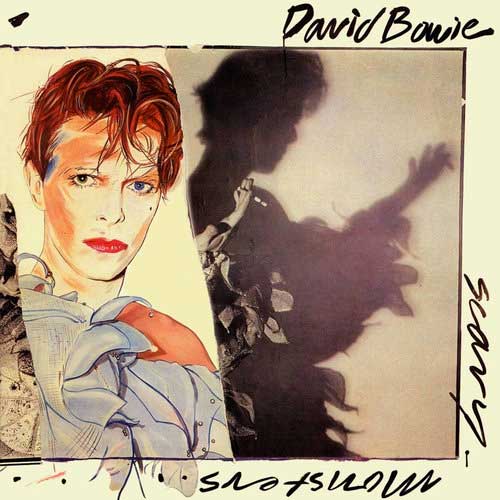

Silhouettes and Shadows. The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), Adam Steiner (280pp, Backbeat Books)

This rambling, digressionary and unfocussed exploration of David Bowie’s 1980 hit album Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) is an enjoyable and informative book, full of surprises and unexpected comments and critical revelations. According to Steiner, the album is made post experimental phase but pre the pop phase that would come next. RCA were unhappy with Bowie’s Eno-influenced albums and suggested a return to the soul of Young Americans which had preceded them, despite critical acclaim and eventual sales for 1977’s Low and “Heroes”, if not so much for Lodger. Bowie was still struggling with on/off addictions, despite living in Berlin in an attempt to get clean, and caught up in thinking about the kind of music he might make next.

The book travels forwards and backwards (and sideways) in time, offers social and historical context, biographical details, authorial opinion, review excerpts, snippets from new interviews with musicians involved at the time as well as critics, writers and Bowie experts, and deconstructions and explorations of individual tracks, each of which gets a chapter to itself. It’s gloriously readable and informative, the book’s loose shape an appropriate response to an album which, although more focussed than Bowie’s previous album (Lodger), which was regarded as an unsatisfactory end to the Berlin trilogy, despite not being recorded or written there. On the back cover Steiner suggests Scary Monsters is the product of ‘Bowie at a personal and professional crossroads’.

For Steiner, the ghosts of Ziggy and Major Tom, perhaps the spectre of glam rock in general, still haunted Bowie, and Scary Monsters is partly about putting musical stakes through their heart, most obviously on ‘Ashes to Ashes’ in relation to the lost astronaut. (Of course, as we know, it didn’t quite work: Major Tom would return for one last appearance on the title track of Blackstar, Bowie’s final album.) Scary Monsters is also about faith and direction, particularly on ‘Kingdom Come’, the cover version of a Tom Verlaine song; and about the pressures, cynicism and ruthlessness of fashion, which Bowie explores in the song of the same title, wondering whether to embrace it or resist it’s siren call.

In a similarly undecided manner, the album offered up a wide range of stylistic musical choices, in some ways similar to the way Lodger was held together using the idea of a travelogue. If the krautrock and ambient explorations of Low and “Heroes” were absent, Robert Fripp’s various searing guitar solos could be seen as a continuation of the powerful and foregrounded guitar work on those albums but also a major part of Station to Station, my favourite Bowie album. Urged by Bowie to ‘Think Ritchie Blackmore’, Fripp was – according to Steiner – able to ‘destablize and enrich the work of his fellow musicians’ on ‘Up The Hill Backwards’ and, ‘unmoor the song, taking it towards strange new territories.’

These new territories were not only created by abstract and intrusive (yet very wonderful) guitar work, but also guttural Japanese vocals and Bowie’s desperate scream to stop the guitar solo on ‘It’s No Game (Part 1)’, Chuck Hammond’s weird guitar synth and Andy Clark’s Moog on ‘Ashes to Ashes’ (as well the track’s postapocalyptic video with it’s solarised beach and black sky), not to mention the self-interrupting, self-questioning and self-mocking chants and slogans of the goon squad on ‘Fashion’ (‘listen to me, don’t listen to me / beep beep’). Despite the sonic layerings and disruptions, not only did Scary Monsters sell, but produced hit singles.

For a while a desire for hit singles and popular success seemed to be the most important thing for Bowie, rather than experiment , subversion or sincerity. It wasn’t until Outside in 1995, an awkward and mostly unloveable collaboration with Eno, that he chose to step outside the pop marketplace he had imprisoned himself in after Scary Monsters. Although many, including myself, liked Bowie’s use of drum’n’bass and electronica on Earthling, and others enjoyed the art rock of Heathen, fans and critics did not join together in acclaim until the surprise release of The Next Day in 2013 and Blackstar, released posthumously after Bowie’s death three years later.

In 1980, while making Scary Monsters, however, Steiner says that Bowie was ‘[e]xhausted by the atrophy of mass communication, being known, beloved, and often misunderstood, where songs are seen as imitations of one’s own life’. The album ‘would stand as an opportunity to look both forward and backward at the same time’, and ‘remains a key moment in David Bowie’s brilliant adventure toward some better place.’ This better place would, of course, involve Bowie falling to earth and learning to live like others (albeit wealthy others) in NYC, and eventually returning to making the innovative and subversive music he was once renowned for, rather than the hit singles which – along with the sales of his back catalogue – helped fill his coffers. Steiner takes inspiration from all of this, ending the main part of his book by stating that ‘David Bowie went further out than most—and inspired us to dream that maybe we could go there too.’ This wide-ranging, eclectic, ill-disciplined and self-assured book also offers useful interpretations and inspiration to the inquisitive reader.

Rupert Loydell