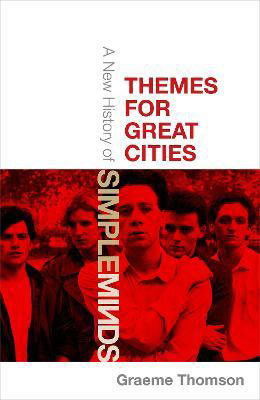

Themes for Great Cities: a New History of Simple Minds, Graeme Thomson

(360pp, £20, Constable)

I know I am not alone in experiencing the formative music of Simple Minds, live and on record, when they were playing alongside or on the same gig circuits as Magazine, XTC, Talking Heads and Wire, as innovative and exciting. Thomson rather hyperbolically sums it up early on in Themes for Great Cities, a new book about the early work of this band:

Before the Sound of Young Scotland and before The Smiths,

pre The Jesus and Mary Chain and Creation, long before the

waves of Manchester, rave and Britpop, Simple Minds were

everything you wanted a band to be. Experimental, eccentric,

evolving, curious and mysterious.

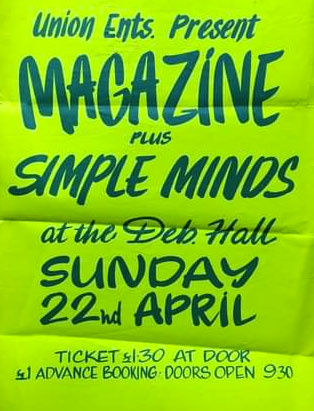

I might quibble with the eccentric but the rest was certainly true. I first saw and heard them supporting Magazine, and was captivated by their sub Velvet Underground songs, particularly the song ‘Pleasantly Disturbed’ which was given a long extended and improvised workout, all vibrato guitar, synths and jagged violin. It was one of the highlights of the first album, Life in a Day, although Thomson suggests it ‘was outdated before it was even released’.

The band would quickly move on, spending time jamming together and creating songs out of loops, riffs and textures. Their second album, 1979’s Real to Real Cacophony, came in a textured blue sleeve and was jerky, noisy, awkward and mesmerising, partly because of its sense of incompleteness. The music critic John Gill suggested that whilst he was ‘not saying Real to Real Cacophony is a masterpiece […] Simple Minds have come up with an album whose experimental successes far outweigh its flaws.’ He went on to note that the band were now ‘expressing their own style to a greater extent’ although he later mentions David Bowie, Peter Hamill and Eno in relation to the ‘completely off the wall’ and ‘shocker of an experiment’ song ‘Veldt’.

For impressionable (and of course discerning, ahem) teenagers like me at the time, desperate to find interesting new music, and seduced by music writers such as John Gill’s and Paul Morley’s literary and critical name-dropping and pretentious musical comparisons (Gill even squeezed jazzer Anthony Braxton into his review because they shared the Arista record label!), Simple Minds somehow combined new synthesizer technology, progrock ambition, krautrock experiment and post-punk rhythmic assertion and attitude to create fluid, dynamic and exciting music. Thomson is more succinct, noting that Simple Minds began ‘making the music they hear in their heads.’

I was hooked, and would remain so for the next three albums: Empires and Dance (1980), Sons and Fascination and Sister Feelings Call (both 1981). James Dean Bradfield, in one of several strange and sometimes out-of-place chapters written by named guests, recalls – with reference to the band live – that

[in] this band everybody is playing a different part. They’re like

a succubus for the music, it is just flowing through them. They

are doing what the unit they have formed demands of them.

When you’re a band you become some weird symbiotic organism.

When a band clicks you just know it, and it’s beautiful.

This symbiosis was reflected in the recorded songs on 1980’s Empires and Dance, which Thomson suggests contains ‘music, voice and words perfectly in lock step’ to create a ‘European psychodrama’ which drew upon memories of Jim Kerr and Charlie Burchill’s hitchhiking trips as well as more recent band tour experiences. Travelling, place and the blurred experience of scenery and time passing by would also inform the band’s two 1981 albums, although by then America was as much in the mix as Europe.

In his NME review of Sons and Fascination and Sister Feelings Call, critic Chris Bohn was not totally enthusiastic. If the music ‘is at times claustrophobically close, at others sharply descriptive of great yawning landscapes and the imminent excitement of approaching cities’, he goes on to suggest a gap ‘between lofty ambition and banal realisation’, suggesting that the band have

exhausted their capacity for new experiences in Europe, as

these disjointed travelogues suggest they were too

overwhelmed by the old/new world of America to do

anything other than report what they saw, folded in with

what they’d heard about Americans elsewhere. Naive

amazement would be enough if they were willing to settle

for expressing just that, but they rather pointlessly present

the knowledge they gained as some enigmatic voyage of

discovery without letting on the location of the departure

point.

‘It is at this point in the narrative where traditionally they [Kerr and Burchill] are accused of participating in the great stadium rock sell out’ writes Thomson, and it is also where I parted company with the band, unable to accept the shift from experiment to pop band that was immediately evident on 1982’s New Gold Dream (81-82-83-84). (Thomson seems unsure of what he thinks, not knowing whether to embrace the band’s success or to criticise, finally trying for both, noting that

Simple Minds finally reached a mass market, deservedly so,

and the beautifully calibrated machine music with a human

twist lost much of its nuance and sleek edges.

and trying to justify it through a kind of pop sociology, suggesting that ‘[i]n many ways, this big, open-hearted version of the band was a more honest portrayal of the group of young men that made the music’.

I’m never sure how a word like ‘honest’ can be used in the arts. Are novelists expected to be honest? Actors? No, so why should musicians. It’s a question I ask because Thomson is clear that this enthusiastic and informative book is mostly reliant on interviewing the band memories, mostly in recent times, a good 40 years on from when this all happened. Even his criticism is mostly muted, and the band seem to wallow in a warm glow of fellowship and camaraderie they share with even previous members (with the exception of original drummer Brian McGee who ‘asked not to be quoted in the book’), not to mention managers and graphic artists. Sleeve designer Malcolm Garret ends his guest chapter by proclaiming that the band ‘never lost their down-to-earth humanity’, and that he thinks the band

had put themselves into a privileged position through hard work

and talent, and never lost a sense of humility about that. They

were always real people, and I count them among the nicest,

friendliest and best people to work with that I ever came across

in the industry.

The book covers one more album, 1984’s Sparkle in the Rain, noting the band’s ascendance into chart success, stadium-filling fame and money, but also offers a Coda where Thomson, Charlie Burchill and Jim Kerr reflect on what has happened since then. Simple Minds’ 5 x 5 tour in 2012 found them revisiting and playing five tracks from each of their first five albums live (with the twinned 1981 releases counting as one album). Burchill notes that ‘the sound is still interesting’ whilst Thomson is clear that ‘Kerr understands that, for many fans, the early Simple Minds albums will always contain the best music that the band ever made’, adding that ‘[t]he knowledge doesn’t eat away at him.’

The band are at peace with their success, and Thomson seems to buy into that, declaring that

Simple Minds earned the chance to find out how far they could

take it, and they did not waste it. No Scottish band, before or

since, has so successfuly exported their music around the world.

[…] Simple Minds moved fast and travelled far.

If at times Thomson seems to allow his interviewees too much slack, and backs away from serious comment and critique, Themes for Great Cities is nevertheless a welcome chance to revisit and contextualise the original post-punk version of Simple Minds before they willingly became something else very different and, to these ears, far less interesting.

Rupert Loydell