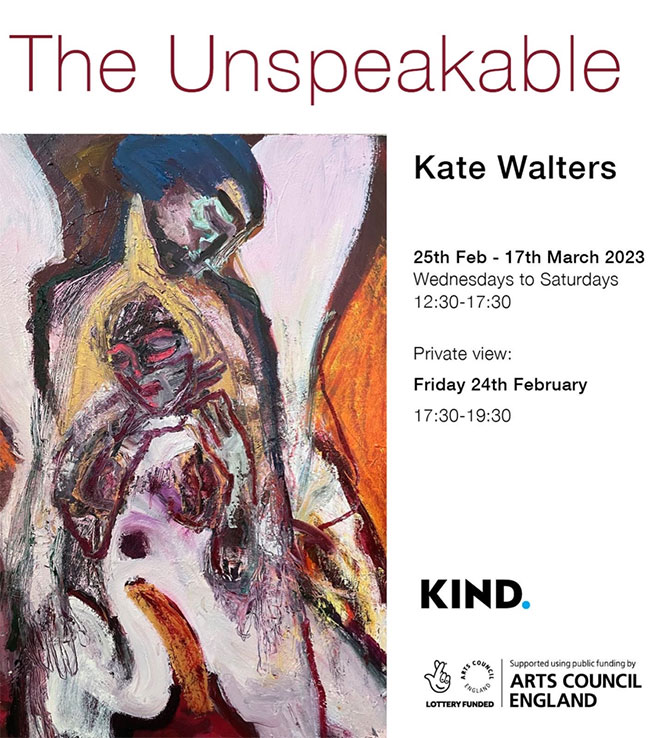

An essay written to support Kate Walters’ solo exhibition The Unspeakable at Studio KIND in Braunton North Devon, February 2023.

The Greek word, ‘Kore’, derives from a root meaning ‘vital force’ and ‘refers to the principle that makes plants and animals grow’ (Agamben & Ferrando 2010 p 6). The Kore is any untethered girl or woman whose sexuality may be yet budding or budding again and again. It is used to refer as much to any unmarried woman who may be sexually active as to one who has not yet awoken to her sexual life. It is also used in reference to those who are old yet still powerful, ‘children with white hair’ such as the Erinyes.

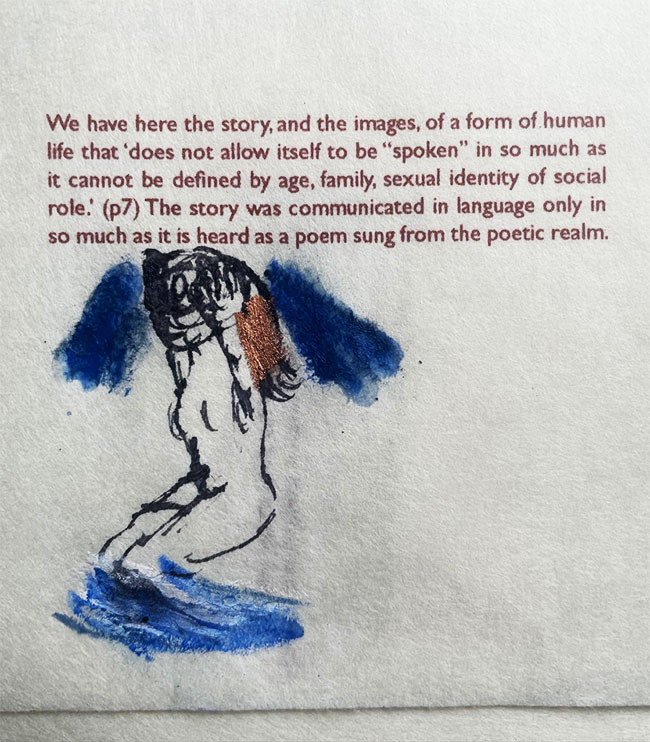

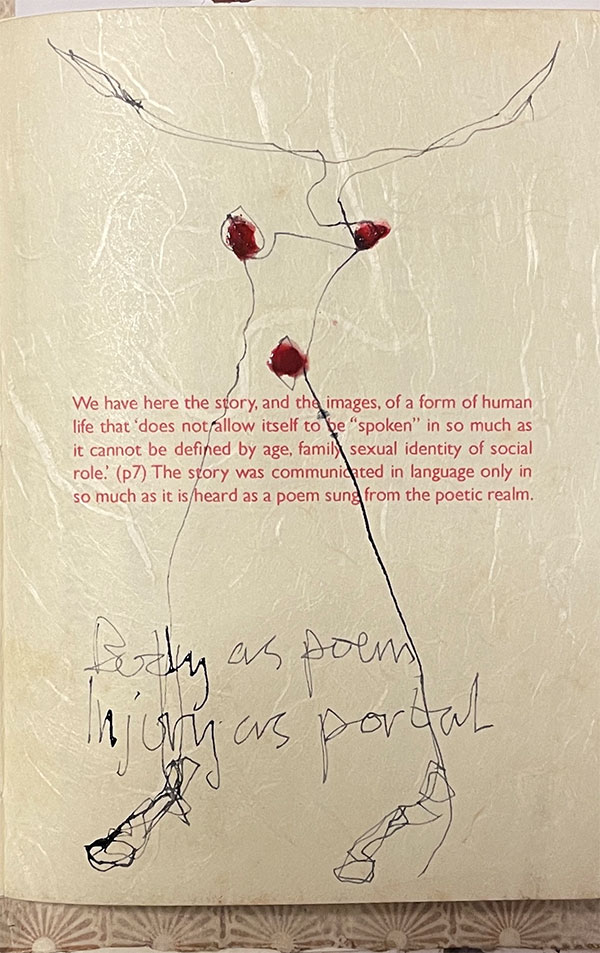

We have here the story, and the images, of a form of human life that ‘does not allow itself to be “spoken” in so much as it cannot be defined by age, family, sexual identity or social role’ (Agamben & Ferrando 2010 p7). The story was communicated in language only in so much as it is heard as a poem sung from the poetic realm.

The poetic realm is imaginal and it speaks directly from the body to the body. But what if Persephone, daughter of the goddess of fecundity, was overwhelmed by her own burgeoning exuberance and sexuality as it pushed up from inside her like an iris budding in the morning? Pushing up and calling towards the Earth around her with the Sea-breeze and the Sun-warmth. The warming Earth, and the Sun and the Sea, are calling back and drawing the budding upwards and upwards.

She is with friends on the cliffs in the warm Spring sunshine, a gentle sea breeze is ruffling the down on their arms, playing around their ears and their knees as they laugh and bend to smell the flowers, picking them in abundance. It is in delight that she is drawn into the face of the flower, kissed into kissing and infiltrated by that irresistible scent; it tickles her nose and slips itself into her, sending a frisson down through her body and out over her skin, spreading and awakening her. What can this be that is stealing over and through her as never before? She doesn’t know what is happening and she can’t stop. Everything is different: the way it looks, the way it feels, the way she feels. Everything is new. Again. Each time she opens her eyes and feels her skin respond. And she is aching for more of it but doesn’t know what it is. This is like it is the very first time. She puts the pomegranate seed in her mouth and nuzzles its sharp flavour with her tongue till it sweetens and creeps down her throat. She is not the one she was before. Everything is gone. No one saw it happen and no one knows where she is. She has disappeared.

And with that sexually creative sensuality comes the silent knowledge of death, unnoticed until too late. Unavoidable. Necessary. Is Trauma what happens when a god takes possession of us without our consent?

‘With Death as my advisor’: prayer child arising from a falling vulva with a contained challenge of aliveness and tension in the line and expression

Trauma: not only the result of annihilatory treatment in the Death Camps.

Trauma: also the silent and unnoticed introduction of death, slipping in where it was least expected and in the very moment when we are opening our budding selves up to the world. The butterfly.

Even if predicted, the unknown event lies in wait until long after it can no longer be avoided.

Trauma: unspeakable.

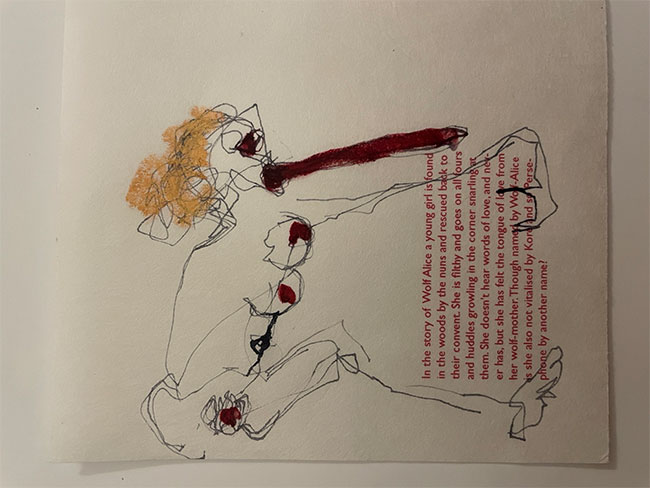

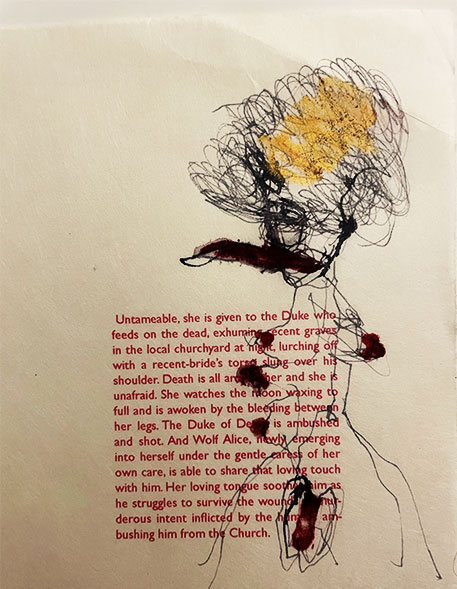

In the story of Wolf Alice a young girl is found in the woods by the nuns and rescued back to their convent. She is filthy and goes on all fours and huddles growling in the corner snarling at them. She doesn’t hear words of love, and never has, but she has felt the tongue of love from her wolf-mother. Though named by Wolf Alice, is she not also vitalised by Kore and so Persephone by another name? Is she not ‘the bud of flesh in the kind lion’s mouth’ (A. Carter 1979)? Untameable, she is given to the Duke who feeds on the dead, exhuming recent graves in the local churchyard at night, lurching off with a recent-bride’s torso slung over his shoulder. Death is all around her and she is unafraid. She watches the moon waxing to full and is awoken by the bleeding between her legs. The Duke of Death is ambushed and shot. And Wolf Alice, newly emerging into herself under the gentle caress of her own care, is able to share that loving touch with him. Her loving tongue soothes him as he struggles to survive the wounds of murderous intent inflicted by the humans ambushing him from the Church.

In The Remnants of Auschwitz Agamben delineates that which eludes being captured by words: the trauma of annihilation. In The Unspeakable Girl Agamben’s exploration of the Eleusinian Mystery rites appears to present an alternative understanding of Persephone’s trauma as being one that leads to an experience of ecstatic re-birth. The essence of this experience refuses colonisation or interpretation, is not restricted to an elite or retained for the select, but is open to all. It cannot be transmitted or described; it can only be experienced in the body. The Kore, the young girl, the essence of vital life, is re-born from the trauma. This is Wolf Alice. This is also Little Kate being brought back to an enlivened beingness through the tiny ink drawings and the paintings.

The paintings in this exhibition of the Unspeakable are like still-shot images from a renaissance of life out of the trauma of the once lost. They pulse with life caught momentarily in an eternal present, balanced between an impossibly uncertain past and a tremulously reached-for future. In Kate Walters’ work presented in this exhibition we see these images being nursed into being out of the inchoate uncertainties of her own traumatic experience which is both hers and that of all of us who, confronted with the shock of the not-understood, continue struggling towards awareness, continue pushing and being pulled towards the sun.

As we can see in the texture and gesture of line, colour and medium, embodiment of ink or oil pigment, these moments of suspension are both powerful and fragile, constantly eluding us and on the point of disappearing.

Our experience in that ‘semantic void’ is to witness and to have testimony of that moment impressed upon us primarily in, not through, our body’s senses. These works are themselves unspeakable because they have to be understood in the moment of being that is held in the body. They are also moments in which seeing the Medusa becomes revelatory rather than deathly.

Little Kate, as she comes into view through the ink spilling itself over the typed words of little books, brings with her something from her past and ours that gets reworked in the very act of her formation and this process of vitalization, of renaissance, appears almost epiphanic. It is for this that Little Kate is also Kore, Persephone, kissing the flower thrusting into her whole face, overwhelmed by her own sex and so vulnerable to being captured and exploited by the male gaze of patriarchal power and having to find an Eleusinian way to resist.

Agamben writes with reference to Averroes (aka Ibn Rushd) that ‘imagination delineates a space in which we are not yet thinking, in which thought becomes possible through an impossibility to think’ (Agamben 2007 p55-6), and that thinking is made possible by uniting (copulating) with the phantasms/images of imagination and memory, ‘which are the ultimate constituents of the human and the only avenues to its possible rescue’ (Agamben 2007 p56).

The image suspended and charged with time requires an experiential union within the poetic and imaginal body of the artist and thereafter of the witness. This is the place where meaning comes into being, where soul is made and where psychic reality is enabled to emerge. The psychic reality of who each one of us experiences ourselves to be, the collective psychic reality of our daily cultural experience, is formed by this unfolding process.

(Edited by Kate Walters March 2023)

Bibliography

‘Agamben & Ferrando 2010’ refers to:

Giorgio Agamben & Monica Ferrando The Unspeakable Girl, translated by Leland de la Durantaye & Annie Julia Wyman. Seagull Books 2014 (ISBN 978 0 8574 2 083 1)

A Carter 1979 refers to:

Angela Carter The Bloody Chamber. Vintage 2006 (ISBN 9780099588115) (quote is from p. 146)

The Remnants of Auschwitz refers to:

Giorgio Agamben Remnants of Auschwitz Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. Zone Books 2002 (ISBN 978 1 890951 17 7)

Agamben 2007 refers to:

Giorgio Agamben Nymphs Translated by Amand Minervini. Seagull Books 2013 (ISBN 978 0 8574 2 094 7)

The Unspeakable by Kate Walters

25th February – 17th March 2023

Open Wednesdays to Saturdays 12:30-17:30

Free entry

‘Trauma is the necessary encounter with an unavoidable catastrophe.’

– Jesse Selkin

Kate Walters’ exhibition of watercolours and oil paintings, accompanied by sketchbooks and poetry, gather together works from the past twenty years as she has moved closer to, and away from, traumatic events in her life.

Kate has recently begun to focus on her inner child, supplying her with a number of sketchbooks in which she can explore, as Little Kate, many partially remembered events, and the pathways to healing that creativity and attention can bestow. These paintings explore the important roles of eros, bodily knowing, dreaming, animal protectors and shamanic knowing in penetrating the areas revealed by awareness brought through trauma.

For more information head to www.katewalters.co.uk