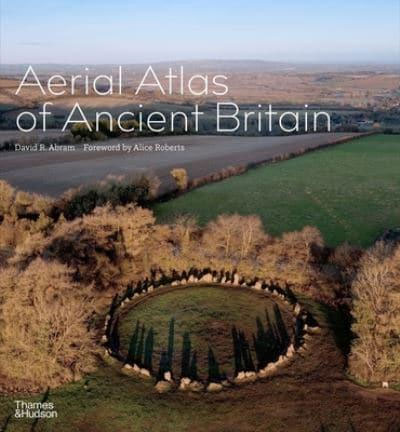

Aerial Atlas of Ancient Britain, David R. Abram (272pp, hbck, £30, Thames & Hudson)

Wow! Normally I’m a bit cynical about photographic coffee-table books, but this new Aerial Atlas is utterly brilliant. Abram thankfully stays away from starry-eyed wonder, gobbledygook occult theories, and postcard views, instead concentrating on archaeology, history and landscape: how the hill forts, tombs, barrows, pits and mounds are situated, their geographical context if you like. Alice Roberts, in her Foreword, talks about walking the landscape of the past, how in fact the past is still physically present with us because our ancestors helped make it, and because of the evidence all around us.

Abram’s own, informative Introduction, tells readers about how he researched and compiled the book, and how this gave him a new sense of Britain, a ‘new mental map’, allowing him to ‘rediscover forgotten horizons’, and consider how different places were important in different times, and how they interconnected. He also makes a strong case for aerial photography and how it reveals ‘[a]lignments and reciprocities’, suggesting that many of these sites could be considered as ‘a form of landscape art’ within ‘ceremonial landscapes’. He finishes by explaining the structure of the book (‘roughly chronological’), also highlights the disadvantages of this ordering (contemporary rather than contemporaneous distinctions), and flags up the fact that each of the four sections has its own introduction. He also notes that out of ‘tens of thousands of prehistoric sites’ he has ‘selected some of the most spectacular and significant’.

And spectacular they are, certainly in the photos gathered together here. Each photo has its own informative text, and many are presented as full or double page spreads, all in glorious colour. The four chronological sections are The Paleolithic and Mesolithic, Neolithic Britain, The Copper and Bronze Ages, and Iron Age Britain, and whilst the first section shows minimal human interventions and traces of occupation – holes and caves, a pit full of bones, the second section is full of fortified hills, barrows, circles and mounds, not to mention standing stones and a flint mine. Some stand alone in wilderness, others are amongst farmland, with ploughed or cropped fields all around, or within clearings in man-made woods or forests. Some are photographed midwinter, with snow light helping capture the contrast of the man-made with the natural, accentuating the shadows and forms of standing stones and protective walls. Stonehenge, Avebury, Silbury Hill and other well known sites are featured here, the last labelled as ‘[o]ne of the great enigmas of British prehistory’.

By the Copper and Bronze Ages there are barrows everywhere it seems, some clustered together as cemeteries, others in orbit around other ancient sites, others part of complex processional routes, those ‘ceremonial landscapes’ mentioned earlier. One my favourite group of photos in the book are the three images of Moel Goedog in North Wales, where a hill fort, itself part of a route involving standing stones and cairns, is trisected by stone walls. The first photo shows the hill from straight above, looking down, the next looks along the ridge the fort is situated on, in the third the point-of-view moves down and back to show the glorious view across an estuary, a bay, the Llŷn peninsula, with Snowdon in the distance. Abram notes the site has not received much archaeological attention, but then also makes a succinct but convincing case for it being ‘a pivotal landform’.

Elsewhere there are intriguing, if not so photogenic, examples of field cultivation in Wiltshire, producing strange stepped areas as a result of ploughing; stone field boundaries and enclosures on Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor; and the White Horse of Uffington, carved into a hill ridge in Oxfordshire.

By the Iron Age, hill forts are becoming more complex and as much about accommodation and farming as defence and protection. Multiple moats and walls enclose the remains of roundhouses or stone buildings, whilst the ground itself still evidences trackways and areas of use. This is the era of Cadbury Castle, Badbury Rings, the very wonderful Maiden Castle (which I made a plaster model of when I was 9) and Old Sarum, a ‘centre of power for over two and a half thousand years’. We visited that from school too, also taking in Salisbury Cathedral and a set of wall paintings full of devils and torture in a church which was supposedly en route.

Abram gives us a separate page entry with detailed information about Iron Age houses, accompanied by a grid of small photos from around Britain, including a couple of my local ancient village site Chysauster. The Wittenham Clumps follow, which I only know from Paul Nash’s paintings and the train window. I had no idea they were part of a hill fort or that Pitt Rivers (who founded the very wonderful Oxford museum of the same name) was an archaeologist as well as an ethnologist! This is apparently another site that has not been fully explored, despite the presence of ‘many circular structures and a street plan’ and ‘a higher concentration of Iron Age coins than anywhere else in Britain’.

The book concludes with a useful list of materials for ‘Further Reading’ and is fully indexed if you want to find something specific, but this is also a wonderful book to dip into and follow geographical or historical threads through. Mostly though it feels like Abram is generously sharing that ‘new mental map’ of his through his wonderful photos. I’ve already got a list of places to seek out next time I’m actually travelling rather than mentally doing so in my armchair.

Rupert Loydell

Fine review! Fun to hear of the reviewer at nine years old also!

Comment by John Levy on 29 September, 2022 at 12:19 pm