ONE OF THE most formidable British vocal talents of recent times, Carol Grimes has been carving a deep notch on the music scene for some 60 years, delivering distinctive takes on songs that range from jazz and blues to R&B and soul. Further, she has been inspired by multitude of influences – recording artists and performers, novelists and poets, social resistance and protest campaigns.

Emerging in the mid to late-1960s and quickly caught up in the large and positive effects of the churning typhoon of swinging London, Grimes has combined singing and songwriting, spoken word and poetry, in a rich gathering of styles, traits that bear a strong relationship to the Beat Generation crew and the ever present pulse of jazz, tributaries which continue to feed her creative flow today.

A key member of several bands over the years including Delivery and Eyes Wide Open, her solo records are well worth comment. Her debut solo album, Warm Blood (1974), was recorded with members of Area Code 615 and the Average White Band and follow-up, recorded in Memphis, showcased the Brecker Brothers, Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn and the Memphis Horns.

She admits a long allegiance to Beat culture and style. Lois Wilson wrote of her magazine Mojo in 2007: ‘Carol Grimes started out as a beatnik busker, celebrating drinkers outside pubs with renditions of “Summertime” and ‘The House of the Rising Sun” in 1962.’

The journalist, describing a 2002 collection by the singer in the same article, referenced Grimes’ ‘intoxicating vocals, equal parts Marsha Hunt, Julie Driscoll and Merry Clayton, turning her song poems – titles “Skinside Out”, “Woman To Child” – into seductive, hypnotic and terrifying incantations.’ Some talent!

In this very recently minted conversation, Grimes talks about the numerous phases of a fascinating artistic life – the people, the groups, the politics, the books – and draws attention to a poem, a spoken word piece, which she dovetails on stage with a legendary work by one of her favourite composers: ‘’Round Midnight’ by Thelonious Monk.

She is interviewed here by Malcolm Paul, a contributor to Rock and the Beat Generation, whose recent review of a Tuli and Samara Kupferberg father and daughter art exhibition in the Netherlands was carried in these pages…

How would you describe your education?

That would be the late 1950s, early 1960s. None of it of any worth. I left a secondary modern school two weeks before my 15th birthday which fell during the Easter holidays, 1959. When you are told as a child that you are stupid, plain and inconsequential. Writing was not for me. People would scoff and mock.

I was 15 when I began to discover the Beat world. I had a job as a live-in mother’s help, near Cambridge. An academic family. My education began after my reading the bookshelves there. Climbing up a stepladder into a tiny bed room, a mezzanine with no door. I read many books there.

Reading those books and meeting new people expanded my horizons. I began to want to be an art student. They always looked interesting. Arty! Breton T-shirts, blue Levi jeans. A black beret. Big boots. The moody look of Parisian arty types. French films. Jeanne Moreau in Jules et Jim, a 1962 French film directed, produced and co-written by François Truffaut. I walked around barefoot! Wore large black sweaters. Jazz clubs when I was old enough! I wanted to write before I wanted to sing. I thought I looked too young to be an authentic Beat. At 20 I looked about 16…

Where did your interest in jazz arise?

In the late 1950s/early1960s. Hearing Ella Fitzgerald on Radio Luxembourg and the US American Forces Network. I joined CND [the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament] after the Cuban Missile crisis. My education really began then. Miles Davis. Lift to the Scaffold. Film music. I still wanted to be an art student!

Did the Beat writers have a significance for you? Did you read particular writers or particular novels or poems which inspired you?

So many. Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell. Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat. Brave New World, Aldous Huxley. Herman Hesse. Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf. Then On the Road, Jack Kerouac. Through that book I found the others.

I didn’t know then, that a lot of life my would be ‘on the road’. And that I would love taking a scat solo and telling a story; I call it ‘scat chat’. It is always a free flow in the moment. ‘Red Top’ from 1947 by Lionel Hampton & His Orchestra is one tune I love to do this to. The story is different each time.

After the Cuban Missile Crisis I joined the CND the march from Aldermaston to Trafalgar Square. Listening in on conversations. Asking myself many questions. ‘What is intellect?’ ‘Will only qualifications do for acceptance?’ I was often afraid to talk.

You returned to the capital in the mid-Sixties…

Yes, back to London, 1965. In Chelsea, 16, Oakley Street.

I moved into a room in a bohemian house. Sheila was the landlady and she knew James Baldwin and Richard Wright. I met and became friends with gay men & women in that house. There was Robert and Ted, gay men, Sue an Australian, a lesbian.

We hung out a lot in the pubs of the King’s Road and Earl’s Court. And into Soho. Live music: my ears were flapping! The Earl’s Court gay scene often centred round the Coleherne Arms where the Windrush [the name of the ship that brought the first wave of post-war West Indian arrivals to the UK] generation of musicians could be heard close at hand.

Russ Henderson began performing at the Coleherne with his band in 1962. He was soon joined by Joe Harriott and Shake Keane, leading lights of London’s jazz scene. The Picasso, the Stockpot, the Chelsea Potter, Cafe des Artistes. Then I met Larry, just out of art school. He was working on the rides at Battersea funfair. He moved in very quickly. Coffee bars in Chelsea and Soho. Listening to Oscar Brown Jr, the Last Poets. Nina Simone. Monk. Miles. Charlie Parker. Charles Mingus. Reading Ezra Pound

With Larry Smart, I visited museums, theatre, art galleries. Coffee bars in Chelsea and Soho. I joined my first band after singing in an alley beside a pub in Hastings. There was a Beat scene down there, some of them living in the caves.

Did the Beat writers have a significance for you? Did you read particular writers or particular novels or poems which inspired you?

Then me and Larry met John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins. ‘Hopp’y died in 2015 aged 77, one of the best-known counterculture figures of London in the 1960’s, not just as a photographer and journalist, but as a political activist. His last lover had Parkinson’s and was a member of one of the choirs I ran in the Neurological Hospital, Queen Square, London. The choir sang at his funeral. A sad day indeed. I have a beautiful signed photo he took of Thelonious Monk playing a piano.

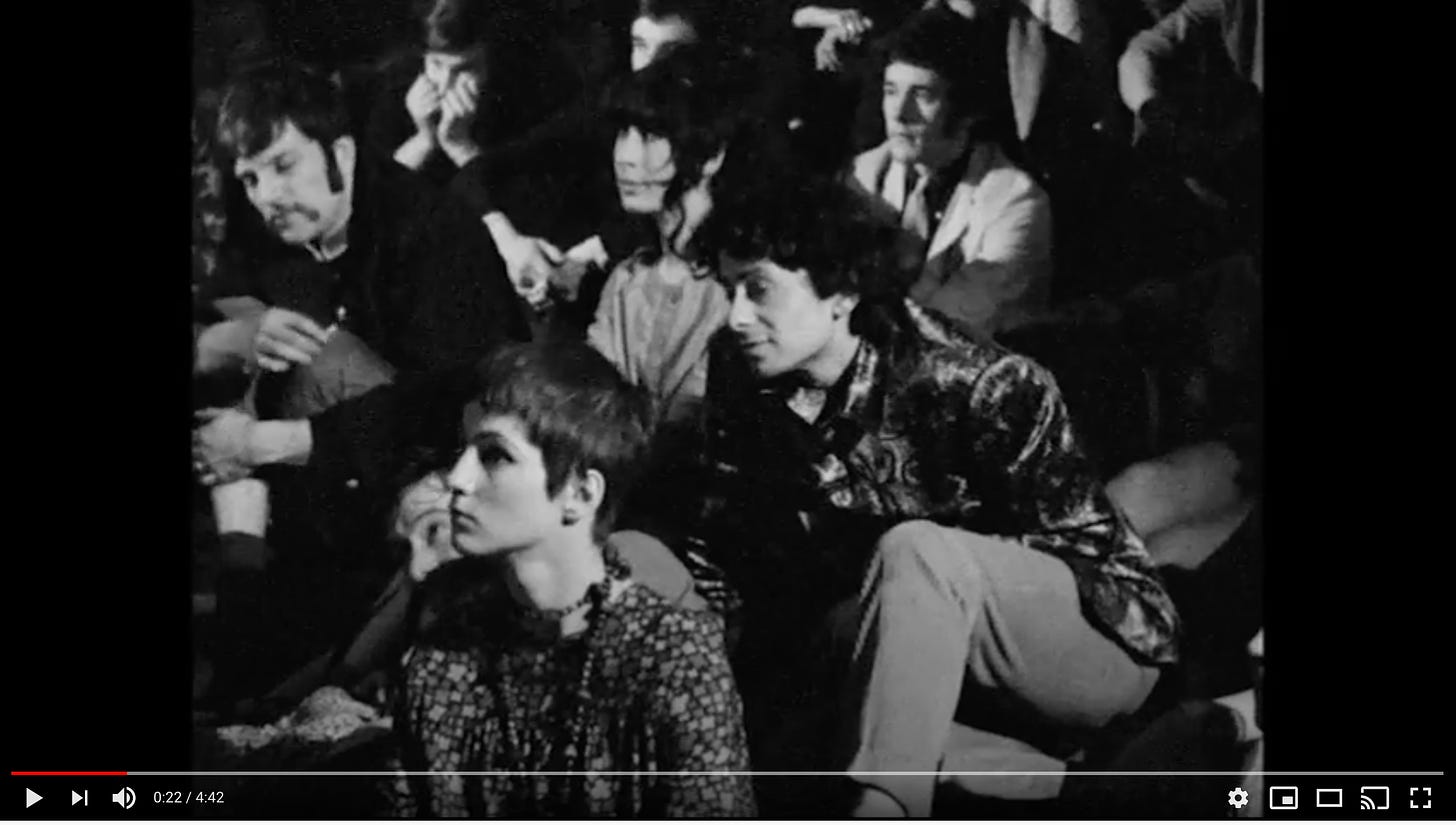

Pictured above: Carol Grimes (foreground) and John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins (centre) together at a 60s happening

On October 15th, 1966, ‘Hoppy’ invited us to the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm for the All Night Rave, the launch of International Times when Beat and hippy culture met and rubbed shoulders. Soft Machine, Pink Floyd. We met Jeff Dexter there.

The Roundhouse played host to an all-night celebration as a ‘pop-op-costume-masque-drag ball’ with guests invited to ‘bring their own poison’, screenings, readings and mysterious ‘happenings’, with the Roundhouse and International Times going on to become two pillars of a British cultural revolution.

So the Beat scene begat the counterculture. I was straddling two coasts. ‘Howl’ and Naked Lunch begat Poetry Review, Better Books at 94, Charing Cross Road, the Arts Lab. I was given a copy of Red Bird by Christopher Logue. Heathcote-Williams came round to see us. Yet more learned people to listen to…

Meanwhile, in London, grey bomb sites, the middle classes moving to John Betjeman green, leafy suburbs. They left behind terraces of mouldering houses, often divided into flats or rooms to let. Flimsy walls and damp rooms.

In Chelsea I became pregnant. We moved to the Grove, an area encompassing both Ladbroke and Westbourne Groves. Me and Larry became a room to visit when finding yourself in those parts. A friend’s sofa, then living in a road long ago branded for demolition in Westbourne Grove, St. Stephen’s Gardens W11, a property that had been managed by Peter Rachman, the notorious slum landlord: four families with one shared bathroom on the first landing.

Counterculture. Feminism. Politics. Hippies. Free love. Beads and trailing dresses. Women at the sink minding babies. Barefoot and expecting.

Are there particular artists who have caught your attention over the years?

Many! In the mid to late 1960s, I loved the West Coast scene: the Doors, Captain Beefheart, explorers all. And at last women being themselves, Joplin and, in London, Julie Driscoll. I met Jo Ann Kelly and other singers during the later ‘60s into the 1970s.

Marc Bolan was around, Paul Kossoff and Nick Drake, tousled hair, young faces blown away as if on the cold winds from the Russian Urals. Looking at my old photos, I was young and they are still young. Now I am getting old and they never will be. Sammy Mitchell, Sandy Denny, Steve Miller, Jo Anne Kelly, Joe Strummer, all gone and, in more recent times, Elton Dean, Pip Pyle and Poly Styrene, Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn and Lol Coxhill, all people with whom I had sung, recorded or shared stages. Ronnie Scott and Pete King no longer preside over Ronnie Scott’s in Soho.

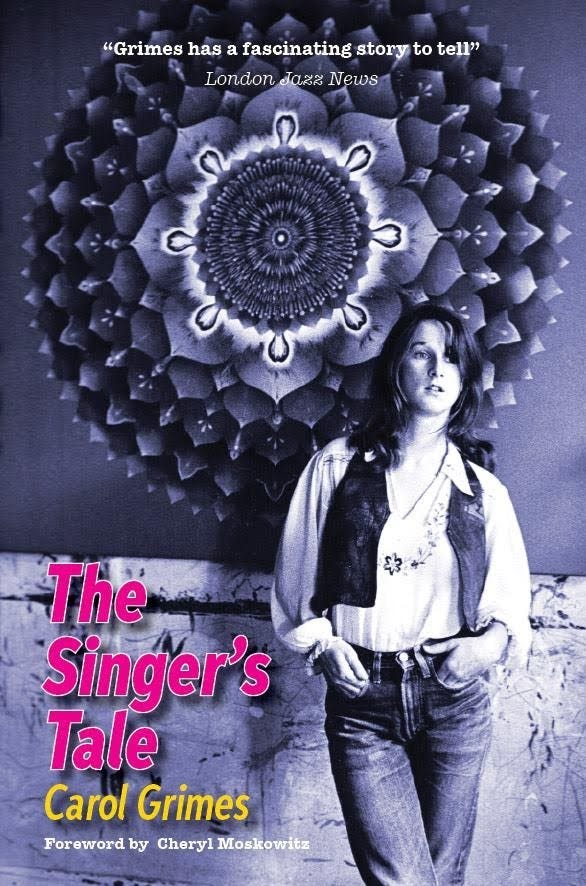

Pictured above: Carol Grimes’ autobiography published in 2017

Meandering around the Portobello Road in the 1960s in my mind are those faces here: Lemmy lurking, always looking on the wild side, and Heathcote Williams, ‘Hoppy’ and Suzy Creamcheese, John Peel and Simon Stable, Jeff Dexter, the Exploding Galaxy and Quintessence, the Pink Fairies, the Deviants and Hawkwind.

Did the Beat writers have a significance for you? Did you read particular writers or particular novels or poems which inspired you?

I engaged with politics, the plight of women over centuries, the obscene way my black friends were treated. Beats and hippies were not necessarily good with women. Many were utterly misogynist. Work to be done. There were a few women who skated the edges of the male hip Beat scene. They are relatively few, but include Diane di Prima, Brenda Frazer, Hettie Jones, Jan Kerouac, Joyce Johnson and Carolyn Cassady.

I always felt that the hippy life was not for me. I had intended to be a beatnik, a daughter of the Fifties artistic revolution, wearing 501 Levis and black sweaters with a cigarette – preferably French – in a black and silver holder, the obligatory book of poetry, Miles Davis on the Dansette record player, living in my own pad somewhere in Central London, Paris or New York.

How would you see that relationship between jazz music and Beat literature? How do you feel they connect?

Free flow. Improvisation. Meaning, experience, need for change. Self expression. Meeting all sorts of different people. In London I met the world, from Africa, India, the Far East, Central Europe, USSR. Some university educated. Even some with PhDs.

What happened for you musically in the 1970s?

A band called Delivery came calling. I joined the band. Previous bands were ruined by management and agents who would not allow me to be me. Or as a woman. Beauty, blond, skinny and posh – that’s what they wanted. With Delivery I managed to get my own words out there. The writing came out from a box under my bed. Sing it, wing it. Why not? I sang about pollution and corruption.

I bought a copy of Kulu Sé Mama, an album by jazz musician John Coltrane. Recorded during 1965, it was released in January 1967. The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper was released the day I brought our son Sam back from hospital in Ladbroke Grove. May 1967.

Please tell us more about your own Thelonious Monk project. How did it come about? Are you a fan of the pianist? I believe you have written your own lyrics to his classic ‘’Round Midnight’. What were you aiming to do with this exercise? What things did you want to say?

I’m very much a fan, yes. In the 1990s I wrote a poem and have performed it live many times; sandwiched within his composition, ‘’Round Midnight’ I sing the song, the band play the sequence and I recite my ode to Thelonious Monk. I wanted convey some of the feelings I felt when listening to his music.

Pictured above: Poster for Carol Grimes’ appearance at Jazz Verse Jukebox, an event at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in 2017

Have you recorded your vocal version of the piece?

I have recorded a few of my poems over the years, both at music venues and the spoken word/poetry gigs.

My writing became more an accepted part of me. In 1985, at the Drill Hall in London, I wrote and produced Lipstick and Lights, prose, poems, song and comedy. My first music theatre production with my band Eyes Wide Open. Guests included the poet John Hegley and the musician Josephina Cupido. It was followed by a second show Daydreams and Danger.

During the 1980, I toured and recorded with several bands including Carol and the Crocodiles and Eyes Wide Open. My own songs came through. And the musicians included Steve Lodder, Maciek Hrybowicz, Angele Velmiejer, Mike Bradley, Paul Neiman, Josephina Cupido and Mario Castronari and the Kick Horns among others. By then, I was doing a lot of performing poetry gigs.

I sang to gave myself meaning. Desperate for identity, belonging, a tribe. I lied, fibbed, made myself up, pretended I was French or American. I wanted to be a beatnik, different from the mob, my life, my upbringing. I told strangers in pubs and clubs that I was from far away. I discovered, quite by accident, a singing voice. But, like the making up of many me’s, I often feel as if I am an imposter.

Age snags and snaps and suddenly I am an old woman. Oh no. Once upon a time I was young. It seems to me that time went too fast. Stop. The end. I am slowly dying. Sitting in my pants eating crisps. A world seemingly shooting itself in the foot. A virus here, a war there, a flood, a famine. Nothing has really changed.

Note: You can visit Carol Grimes’ website here – https://carolgrimes.com/

See also: Malcolm Paul’s art review, ‘Exhibition #2: Tuli & Samara Kupferberg’, May 28th, 2023