From out of the marijuana-induced haze of Kathmandu in the 70s, a lone landmark appears, as evanescent as ganja smoke, as effervescent as a hash high.

In the seven years from 1972-79, one small room in an ancient Jhochhen house emerged as a beacon for hippies, poets and artists. The Spirit Catcher Bookstore, founded and operated by hippies who were leading figures in Kathmandu’s hippie arts scene, bought, sold and traded in books. But reflecting the spirit of the hippie movement, it also organised weekly poetry sessions and hosted a who’s who of emerging and established artists who had made Kathmandu their home.

Although its opening hours were 12 noon to 8 pm, the bookstore assumed the shifting moods whoever was in charge, and there were as many of them as the number of years the bookstore operated.

Writer Terry Tarnoff, who operated the Spirit Catcher for nearly a year and a half in 1974-75, recounts in his memoir The Reflectionist that at one point he “sold marijuana under the counter in an effort to keep the whole thing… floating” while another in-charge “stol[e] two months’ rent money from the till” while another “nodded off in druggy stupor behind the desk of the [bookstore] […] while customers took books, left books and made up their own prices”. He best describes the bookstore’s delicate existence when he says, “I open when I want, close when I want, and hope the place is still there when I return.”

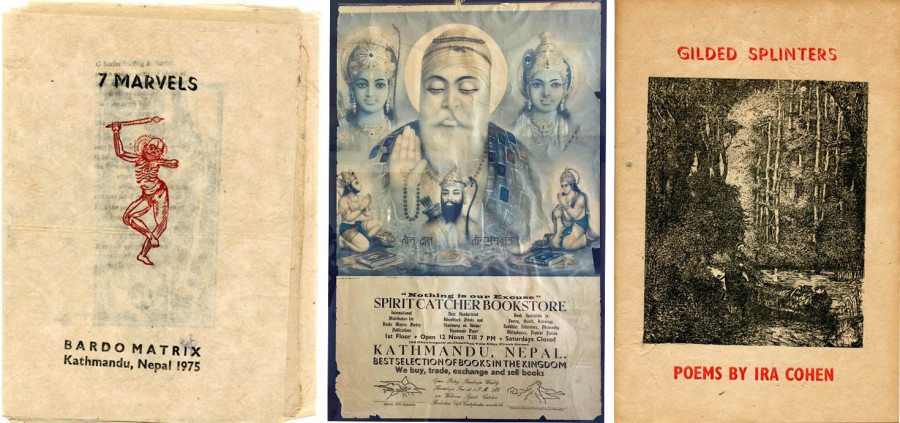

The Spirit Catcher Bookstore’s broadsheet, published on rice paper.

Keeping the dream alive

The Spirit Catcher Bookstore opened with a dream, belonging to a man named John Charles Chick.

Chick arrived in Kathmandu in 1970, when Kimdol, in the foothills of Swayambhunath, had already become an abode of hippie artists, musicians, poets and writers. Chick, along with his partner Regan Heavey, was among the first group of artists for the original Bardo Matrix, a woodblock printing press that started in the US state of Colorado. Before coming to Kathmandu, he’d moved between London, Paris and Morocco.

“He’d talk a lot about his Boulder days and always harboured a dream of owning a bookstore,” recalls Heavey.

Chick had come with the intention to stay, and opening a bookstore would not only bring his dream to fruition but also provide him with a means to live on in Kathmandu.

By late 1971, Chick and Heavey had been joined by Ira Cohen and Petra Vogt, and Angus and Hetty MacLise, two couples that Mark Liechty says, in his book Far Out: Countercultural Seekers and Tourist Encounter in Nepal, were “part of nearly every iconic movement and happening that we now associate with the 1960s youth counterculture.” Cohen was a reputed beatnik poet and a photographer who had lived in Morocco before feeling he needed to be in the ultimate hippie destination, Kathmandu. Vogt was a German actress, model and artist, and a member of the experimental Living Theater group. Angus MacLise, former drummer of the pioneering alternative band The Velvet Underground, was also an artist, and had left the band after finding the schedules and instructions of the band too limiting to his free spirit. He’d headed out to Kathmandu with his wife Hetty, an artist, musician, poet and muse, and their son Ossian. In Liechty’s words, these four were to become “pillars of the Kathmandu hippie expat community”.

However, by the mid-1970s, Liechty says that Kathmandu was more like “a remnant” of the countercultural hub it represented in the 1960s. What once seemed like “youthful optimism increasingly looked like a naïve escapism,” he says. “Most hippies went home, got jobs, and returned to their middle-class birthrights. But some stayed on, trying to keep alive the dream of a nonconformist and spiritually oriented, culturally attuned creative community in exile.”

Cohen and Vogt and the MacLises were among the leading figures in this group of holdouts. Heavey reminisces there’d be soirees consisting of poetry recitations, writing, playing music, and she and Chick often hung out with the two couples and other hippie artists, mostly in Ira’s house.

“The Spirit Catcher Bookstore was born around 1972 in this backdrop,” she says. “In Kathmandu, John had found a group of artists with whom it was possible to realise his dream.”

“In Native American culture, the Spirit Catcher, which is also called dreamcatcher, is a homemade circular frame of wood filled with a leather lattice and feathers sewn in. They hang this close to a baby as it sleeps to protect its spirit from being ‘stolen’,” says Heavey. “With the Spirit Catcher Bookstore, John and everyone else involved in its conceptualisation wanted to protect the spirit of the hippie movement—the free spirits, the arts and everything about love and being unconventional—that they saw was dying.”

The hippie spirit in books

Abhi Subedi was a student of English Literature at the Tribhuvan University in the early 1970s when he was drawn to the bookstore for its eclectic selection of books of English poetry, literature and philosophy at very cheap prices.

“The hippies were more than just smoking freaks who wore long hair and beards and walked about in fancy, colourful dresses,” says Subedi. “They were readers and great lovers of books. They were university-educated and many spoke French and English. The Spirit Catcher Bookstore was evidence of just that spirit of the hippies.”

Fed up with the West’s preoccupation with materialism and consumerism, the hippies were drawn towards spirituality, Buddhism and Hinduism and eastern mysticism, and to travel, different cultures and languages. In his memoir, Tarnoff lists a selection of the books that customers could pick up from the Spirit Catcher’s shelves: “We had the Spanish translation of the Bhagavad Gita, an Amharic version of The Tropic of Cancer, a mahout’s guide to Sri Lankan elephant commands, a Swahili translation of Mao’s Little Red Book, a book of mountain climbing tips written in Braille, a compendium of long-dead currency conversations, copies of The Tibetan Book of the Dead in Egyptian and The Egyptian Book of the Dead in Tibetan, Cheiro’s Language of the Hand, Aleister Crowley’s Magical Diaries, Madame Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine, the complete works of Herman Hesse minus the missing pages, Kazantzakis in the original Greek, Dante in the original Italian, and a book of Russian fairy tales in faded Cyrillic.”

Subedi, meanwhile, remembers the bookstore primarily for its books of criticism and ideas. Books like Herbert Read’s Education Through Art, Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, Jean Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, and others by Heidegger, Jean Genet, Gregory Corso, and other existentialists and authors of the beat generation.

“The hippies were countercultural. They represented the anti-values, anti-conventional, social norms and countercultural movement, a time of freedom and free thinkers and spirits, and the selection of books in the bookstore reflected just that spirit,” says Subedi.

With its shelves full, the bookstore became a popular pit-stop for book lovers, expats as well as travelling hippies. A small group of young Nepali youths like Subedi were attracted by the cheap books while for others, it simply served as a place of hangout, smoke a chillum of hashish or ganja, and chat.

For whatever reason, the bookstore was growing and attracting dedicated customers. Chick, Cohen and MacLise saw this as an opportunity to bring them together into artistic pursuits embodying the hippie spirit. Cohen suggested that poetry meetings would be a great way to bring together poets as well as readers and anyone interested in art. Chick and MacLise agreed.

Jimmy Thapa says designing a cover for Spirit Catcher’s poetry series inspired him to pursue arts seriously. PHOTO COURTESY: LUCIA DE VRIES

Poetry readings to publications

American expats Susan Burns and her husband William (Billy) Forbes became regular participants in the poetry sessions after arriving and settling in Kimdol in the early 70s. Every Thursday around seven, they walked through the rice fields down Kimdol and crossed the rickety bridge over Bishnumati River to arrive well ahead in time for the sessions.

“They would be crowded,” says Burns of the sessions. “There’d be hippie expats and hippies who were just travelling. A host of colourful characters, gypsy-looking people in all sorts of different tie-dye costumes, who came from every corner of Europe, Canada, Australia and America. There’d be local Nepalis too, mostly hanging out and watching the excitement.”

As the crowd gathered, chillums got lit and smoke filled the room as did the chatter of participants, says Forbes. Cutting through the smoke and chatter, Cohen, who was the central figure in the readings, started the event when the clock struck 8.

The couple remember that Cohen and MacLise often read, and so did Roberto Valenza, who was a singer and a poet, and Terry Tarnoff, a writer and musician, and Jane Falk, an American poet.

And it wasn’t simply poetry. Anyone could share anything they wanted to—prose written recently, an anecdote of meeting interesting characters or seeing beautiful places on the Magic Bus journey, a journal entry, a passage from a book. Anything at all. Often, there was also musical accompaniment with MacLise on his drums, Vogt on violin and Tarnoff on the guitar and harmonica.

As poetry and music rang throughout the room, participants drank, smoked or did drugs, the sessions stretched deeper into the night and, as Tarnoff says, “ended whenever they ended”.

“The movement was a lot about travel and adventure, reading and creativity, meeting new people, and being their own selves,” says Burns. “The sessions were vibrant ways to reflect the hippie spirit by bringing together people who were travelling and engaged in creative works, people full of ideas, all in one place to interact.”

Before long, the poetry sessions at the Spirit Catcher became a must-see attraction for expats and tourists, and the bookstore was even listed in a traveller’s guide of the time. Cohen recalls in his 1995 article ‘The Great Rice Paper Adventure Kathmandu, 1972-1977’ that by the mid-70s, these sessions had contributed to creating a thriving poetry scene, which, in turn, paved the way for Spirit Catcher’s next project—a unique printing odyssey on handmade rice paper, which he termed “the great rice paper adventure”.

In Kathmandu, Chick had continued his Bardo Matrix imprint and now, with Cohen and MacLise’s zeal, they collaborated on a series of poetry collections entitled the Starstreams Poetry Series.

“This project specially embodied the hippie spirit because it was a collaborative effort involving Nepali, Tibetan and hippie artists and poets. It experimented with various inks, bindings and covers, and showed appreciation for the Eastern woodblock arts,” says artist Jimmy Thapa, who befriended the hippie artists and designed a book cover for their project.“But what captured this spirit most was that it published poetry books, broadside newsletters and pamphlets featuring the works of hippie poets, writers and artists.”

The series started in 1974 with Way Out: A Poem in Discord by the beat generation poet Gregory Corso. By 1977, it had published several collections by countercultural poets Paul Bowles, Charles Henri Ford, Jane Falk, Iris M Gaynor as well as Cohen and MacLise, thus ensuring that important countercultural literature received a place in the international literary scene.

This poetry series, as well as other rice paper publications, took on a life of their own, and today they are not only valuable collectibles that are sold online for as much as $600-700, but potent reminders of the hippie movement and how the Spirit Catcher Bookstore played an important role in Kathamndu’s burgeoning art scene.

“That where I got initiated to Sartre and the many ideas that shaped me,” says Abhi Subedi. POST PHOTO: SANJOG MANANDHAR

Dreamers at home

But a series of forces would intervene to puncture the holdout hippies’ attempt to “keep alive the dream”. One important cause was the Nepal government’s ban on cannabis in 1973. In fact, Kathmandu being a source of cheap cannabis was a primary reason it had become the hub of the hippie movement, where an important element was openness to the use of mind-altering drugs. So when Nepal government banned the sale of cannabis, it caused the hippies to leave, charting the end of an era. By the late 1970s, this exodus only increased, as it coincided with, as Cohen says, Kathmandu’s increasing modernisation and commodification.

Hard drugs were also taking their toll, with many hippies falling moving on from cannabis and psychedelics to harder fare. Among them was Angus MacLise, who died after years of struggling with hard drugs. The loss of an ardent supporter, along with the drop in daily earnings, ultimately led to the closure of the Spirit Catcher Bookstore.

But for Subedi, there were other factors behind the failure of the bookstore, namely that those who ran it did not learn much from Nepal and remained very Western. In Liechty’s Far Out, he says that they “never left the Swayambhu area… they had some kind of very imaginative microcosm, a kind of attachment that they had created on their own. And that’s where they lived and felt comfortable… But they saw no need to open up [to a world beyond their own].”

Yet when the doors of the Spirit Catcher closed in 1979, it had inspired Nepalis by the same ideas of freedom, humanity and love that its founders had dreamt of protecting. Subedi became close friends with the hippies who remained, including Cohen, and kept alive the more literary and artistic aspects of the hippie movement.

Today a respected educator, poet and writer, Subedi says, “That’s where I got initiated to Sartre and the many ideas that shaped me and continue to impact me as a teacher. I bought so many books there and still cherish them. I often heard great discussions going on, quiet and nice among five or six people.”

The influence was no less for Thapa. He’d sold hashish and marijuana from his dispensary Jimmy’s Wagon for a living, but behind the counter, he privately ran his pencil on his sketchbook. His collaboration with the bookstore for the Starstreams poetry series and participation in the poetry readings would inspire the artist in him.

“I wasn’t very confident when Petra and Ira suggested I design the cover for The Gilded Splinters, but they pestered and I did it anyway,” says Thapa. “I enjoyed the designing process so much that it opened the floodgates of my creative passion. That was the only time I designed for them, but the inspiration was so big that I’ve not stopped since.”

Inspired by Cohen and the others, Thapa continues to write poetry today, fusing it with his art. His paintings blend colours, poetry and astronomy as integral elements, and espouse a deep love and concern for nature and animals, imparting messages of humanity, love and spirituality—the same ethos embodied by the hippie movement.

And this is how, through the life and work of individuals like Subedi and Thapa, decades on from when it all started, the dream the hippies hoped to protect through their tiny, dusty room in Jhochhen lives on.

Prawash Gautam

Prawash Gautam is a freelance journalist based in Kathmandu.

An excellent article, I visited Kathmandu in the mid 80s and there was still the vestige of a hippie culture in places like Thamel and Freak Street but now Kathmandu’s polluted atmosphere has driven any such culture away to Lakeside Pokhara where there is a thriving dance culture. A big change from the 60s and 70s is the presence of Russian and other east European visitors, now no longer shackled by Iron Curtain restrictions. Visitors to Kathmandu can still come across palimpsests of the old hippie/beat culture underneath the more modern tourist oriented city.

Comment by Christopher A Farmer on 12 January, 2020 at 12:32 pmsee guardian G2 Life& Arts page 10 today Himalayan headbangers: heavy metal in Nepal

Comment by jeff cloves on 13 January, 2020 at 4:45 pm