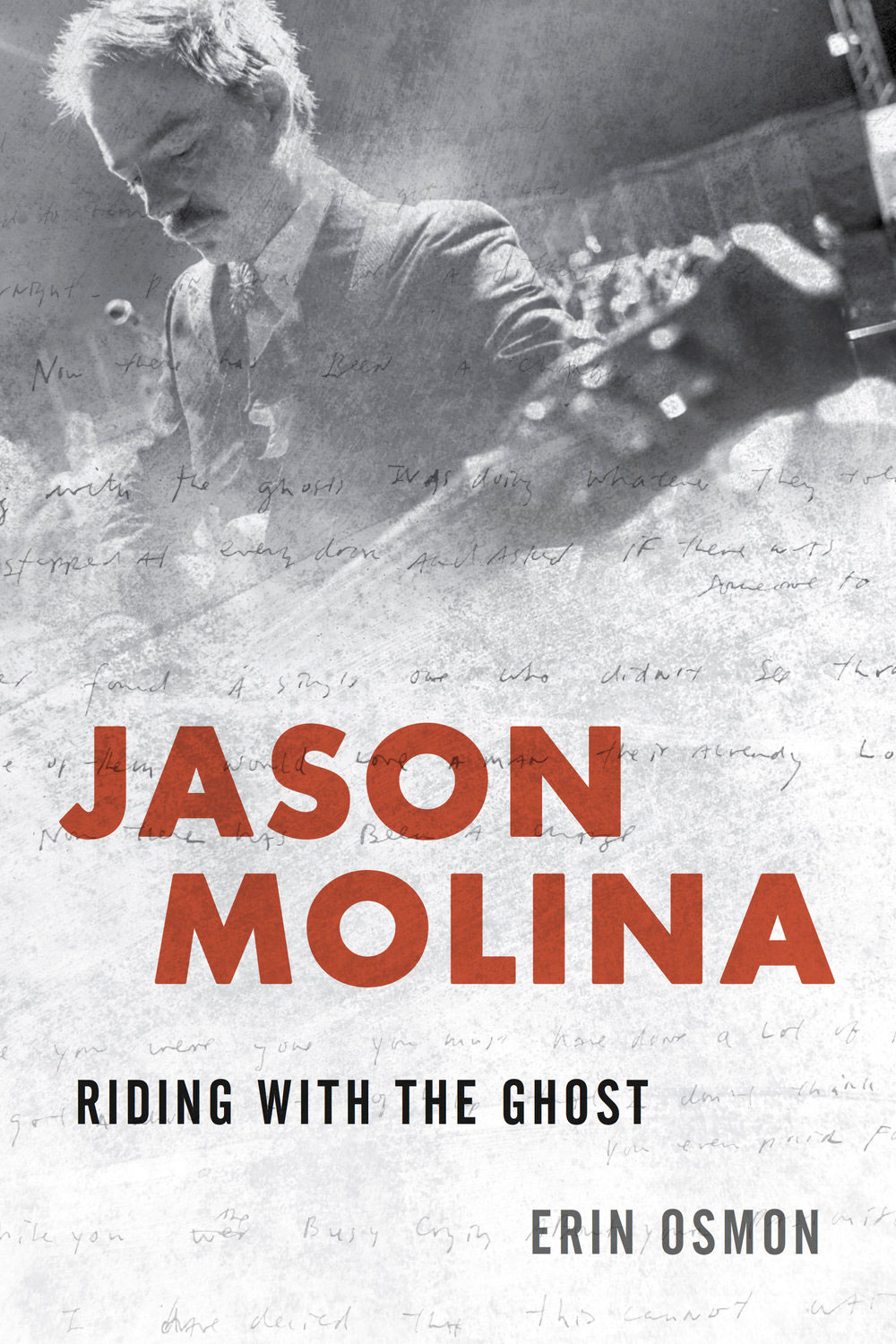

Jason Molina: riding with the ghost

Erin Osmon (Rowman & Littlefield)

‘I built my life out of what was left of me

And a map of an old horizon’

– Jason Molina, ‘The Old Horizon’

Biographies of musicians are strange things. Do we really need to know about relationships, family, influences etc., or should we just listen to the music? Contextualisation can be a strange thing, often taking away any mystique, sometimes reducing the music to merely a gathering of events, emotions and reportage, ignoring the creative catalyst and processes that any composer has to find and use.

Jason Molina, however, is one of those musicians so deeply embedded in his own work, and this book so empathetic and informative, written with such a light touch, that the biographical story told here can’t help but aid us to understand the creative blooming and alcoholic demise of a great, somewhat neglected, musician.

Erin Osmon gives us enough plain biography to situate Molina in the strange hinterland of the American Midwest, before telling us how he escaped to go to college where his musical career starts in earnest with self-produced tapes. His band Songs: Ohia would quickly gain a cult following as well as a record deal with Secretly Canadian, an indie label who would support Molina throughout his prolific career, with solo and collaborative albums as well as discs by Magnolia Electric Co., which Songs: Ohia mutated into.

Osmon captures both the excitement and tedium of touring, the friendships and divides between the musicians and those they worked with, as well as the camaraderie of indie-rock networks that Molina and his band were able to plug into. There are plenty of high jinks here, great gigs and critical acclaim; but also depression and discontent, drugs and drink. Molina could be cruel – to himself and his friends and fellow musicians, and he drowned any regrets about this, as well as bolstering his courage to be awkward and in charge, through alcohol.

As with many such self-abusers, it takes a while for his addiction to be noticed; and often, this is only in retrospect, as those who Osmon interviews for this book sometimes note. Too many people allowed Molina to hurt them, and hurt himself, in the name of the great songs he was writing. They are full of melancholy, nostalgia, travel and loss; are beautiful electric elegies to buy into and share. Osmon suggests that Molina often relied on a preferred collector’s set of metaphors, which mirrored the very real events of his life. He sang of moons, trains, ghosts, flowers, wolves, and bells, providing a sort of tactile connection to his studies and surroundings and to the celebration and suffering he felt inside of himself.

He was heralded a balladeer of heartbreak, but in reality found tremendous hope in the sad songs he wrote and recorded.

Molina’s songs are not morbid autobiographical wallows, however. His ‘set of metaphors’ give a poetic, literary element to the songs, and like many songwriters (such as Neil Young, John Martyn and Nick Drake – though Molina sounds like none of these) allow listeners to buy into the music, sharing and interpreting them for ourselves.

Molina could never understand why he wasn’t more popular, but then at times he could also not understand why anyone would listen to his music. Caught in this quandary, separated from his wife, at odds with musicians, constantly arguing with himself, he sank into drink, to the point where he could not create or record the music he needed to. His long attempt at sobriety, with visits to rehab, was eventually made public by his record label as fans wondered why a tour had been cancelled and no new music was forthcoming. Molina was supported by his ex-partner, friend and bandmates throughout this process, but eventually it failed, and all too soon Molina was dead.

Erin Osmon is a great biographer, writer and critic. She has used new interviews to weave an empathetic and informative story around Molina and his music, without turning him into a martyr, without trying to make him even more of a cult figure than he has become. She does not condone or condemn, simply tells it straight. Here is the story of one creative spirit who could not cope. Here is how he lived and made the music he left behind. Read and listen: it is the story of how music is made.

Rupert Loydell