One of the beauties of a William Wyler retrospective as big as the one that the Cinemathèque Française has currently mounted in Paris is the chance to see the immense variety of his work. I don’t think as thorough a retrospective (41 films, including some of the silents) has been screened since the 1996 Berlin Film Festival.

The Cinemathèque has also posted a deeply researched web page with so many layers you can get lost in them. One pleasure of the site is the rarely seen stills of Wyler with his actors behind the scenes. Another is an oral history (much of it, I’m glad to report, credited to this Wyler biography).

An aspect of Wyler’s personality that runs like a motif through his career was the idea of not repeating himself. Wyler always said to friends from his earliest days, and later to the press, that one of the challenges for a director was to make as many different kinds of pictures as possible. This eclecticism tended to hurt his reputation with purists who preferred to think of artists as obsessed by a single lifelong subject. In their view, the artist’s entire output may be seen as variations on a theme. And anyone whose body of work does not conform to that pattern may be regarded as deficient: lacking depth or purpose or — the ultimate deficiency — a true calling.

An aspect of Wyler’s personality that runs like a motif through his career was the idea of not repeating himself. Wyler always said to friends from his earliest days, and later to the press, that one of the challenges for a director was to make as many different kinds of pictures as possible. This eclecticism tended to hurt his reputation with purists who preferred to think of artists as obsessed by a single lifelong subject. In their view, the artist’s entire output may be seen as variations on a theme. And anyone whose body of work does not conform to that pattern may be regarded as deficient: lacking depth or purpose or — the ultimate deficiency — a true calling.

“My father was a bit hurt toward the end of his life that the variety of his films was not appreciated,” his daughter Melanie Wyler told me for the biography. “Everyone thought Hitchcock was great because he stuck to the same thing. But my father used to say, ‘He’s a prisoner of the medium.’ I remember they had a conversation about it. Hitchcock said he was jealous. ‘You can do any kind of film you want. I can’t. They won’t let me.’”

Wyler arrived in Hollywood when he was nineteen years old and the movie colony was still an open-air circus on the outskirts of Los Angeles.* His first picture, a silent Western filmed less than two weeks after he turned twenty-three, launched a directing career that ranged from “Jezebel” and “Wuthering Heights” in the 1930s to “The Little Foxes” and “The Best Years of Our Lives” in the ’40s, from “Roman Holiday” and “Ben-Hur” in the ’50s to “The Collector” and “Funny Girl” in the ’60s. No Hollywood director had a more intuitive approach to the subtleties of acting performances or went to the extremes he did to shape them. And his pictures not only resonate with poetry and humor, they offer psychological maturity and sophisticated treatment of character more typical of literature than movies.

Wyler used to say he started his directing career as an “assistant errand boy.” It was no exaggeration. In 1922, at Universal Pictures’ sprawling studio in the San Fernando Valley, he began on the swing gang sweeping sets at night. A quarter of a century later, the University of Southern California invited him to give the commencement address to the graduating class of its School of Cinema-Television. Wyler, who spoke three languages but never graduated from high school, called up his friend Robert Parrish, an Oscar-winning film editor, and asked him to lunch.

“I’ve just been offered what I think is an honor,” Wyler said, “and I need your advice.” At Musso & Frank, the Hollywood hangout, they each ordered a Bloody Mary. “Didn’t you go to USC?” Wyler wanted to know. Parrish, who’d recently become a director, said he had. “What’ll I say?” Wyler asked. “These kids are thirty years younger than I am.” “Tell ’em what it’s like to direct Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart and Laurence Olivier. Tell ’em what it’s like to win Academy Awards. Tell ’em what it’s like to argue with Sam Goldwyn.” Wyler grinned and sipped his Bloody Mary. “That’s all there is to it?”

“That’s just bullshit to fill in the time,” Parrish said. “After that you ask if they have any questions. They’ll ask you about the change from silents to sound, who’s the best cameraman you ever worked with, the best cutter, the best producer, the best writer. Then one of them will ask you the key question.” “What’s that?” “How do you become a director?”

Thirty minutes after Wyler took the podium at the commencement, Parrish remembers, a newly minted graduate stood up at the back of the auditorium and asked precisely that. The audience broke into loud applause.

“I’ve known many directors in my day,” Wyler said, “some good, some bad, and lots in between. But I don’t know of any who became directors in exactly the same way. Ernst Lubitsch, John Ford, Lewis Milestone, Jean Renoir, and others are great directors. I don’t think any of them became great by following the same rules.”

Then he launched into a streamlined version of events surrounding his arrival in America — all of it entertaining and most of it approximate. (Like many of the film colony’s early immigrants, he was born in Europe.) When he got to his experience on the swing gang and how he made it up the Hollywood ladder, the audience was hanging on his words.

From left: Wyler with Samantha Eggar, Terence Stamp,

and Federico Fellini during filming of ‘The Collector,’ 1965.

“Part of my job,” he explained, “was to sweep the street in front of the cutting department. As I was doing this one night, I saw a man standing outside leaning against the building. He was the head of the cutting department, and he had an unlit cigarette in his mouth. He said, ‘Got a match?’ I said yes, because I smoked too. He lit his cigarette and offered me one. I lit mine and leaned against the building with him. After a while, he said, ‘We can’t smoke inside because we work with nitrate film and it’s highly inflammable.’ He thanked me for the match. I thanked him for the cigarette. And we went our separate ways.”

The next time Wyler was on the night shift, he sneaked into the head cutter’s room and set up a long-distance smoking arrangement. “I got a piece of copper tubing from the machine shop, put an ivory cigarette holder on each end and ran it from the cutting bench, through the window, to the outside. I went out and lit a cigarette and put it in the cigarette holder on the end of the copper tube. Then I ran inside to the head cutter’s bench and sucked until the smoke came through. It worked. You could now smoke in the cutting room and not blow up the studio.”

When the head cutter discovered the setup, he sent for Wyler and offered him a job as an apprentice in the cutting department.

“I jumped at the chance. I liked the work, I learned fast, I kept the copper tube supplied with cigarettes, and I was soon promoted to assistant cutter. Before I knew it, I was invited to address the graduating class.”

Despite his extraordinary accomplishments and wider public recognition in recent years, Wyler — gutsy, beguiling, unpretentious — still remains pretty much hidden from view, almost as invisible as the cigarette from that cutter’s bench. But at least his reputation flourishes among knowledgeable insiders and his pictures, which once were touchstones for an entire generation of moviegoers, have not been relegated to the distant past as readily as they used to be.

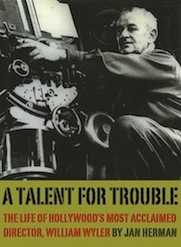

* Excerpt adapted from the prologue of A Talent for Trouble.