David Lynch. His Work, His World, Tom Huddleston (240pp, hbck, £35, Frances Lincoln)

I’m a big fan of David Lynch’s work, and so – clearly – is Tom Huddleston in this beautiful new ‘Unofficial and Unauthorized’ critical biography. To start with, however, I didn’t think we were going to get on. In his ‘Introduction’, Huddleston trots out a number of clichés: that Lynch was ‘a character’ (whatever that means), ‘the last of the rock star directors’ (ditto) and that Lynch’s work is/was ‘deeply personal’, as if the idea of personal or true somehow leaks through and overrides whether a film (or painting, or photo, or book) is good or not. Better is his discussion of ‘Lynch’s own primary motivation as an artist and storyteller, namely the act of discovery’, including Lynch’s own statement, that ‘We are all like detectives, trying to figure out the meaning of life.’

I’m happier with that, because 1. none of us in the end know anything and 2. I believe good art is about questioning not offering answers. Lynch’s work seldom does the latter, which is why it confuses and upsets people but also continues to bemuse and intrigues audiences. Once we’re past his ‘Introduction’, Huddleston seems to agree and move on from the platitudes, which I’m glad about. Seems we will get on just fine, after all.

His first chapter is about Lynch’s ‘Early Life and Short Films’, 24 years in 16 pages. It gives us the basic facts of Lynch’s childhood then thoughtfully considers the lasting effect and representation of 1950s style, music and food (Huddleston refers to ‘its unique sights, sounds, tastes cars and clothing) in Lynch’s work and also discusses how Lynch was, even as a teenager, fascinated by the fine art world, Europe, and American cities. He undertook a trip to Europe, trying but failing to find painter Oskar Kokoschka, and responded to cities such as Boise, Idaho, New York City, and Boston (which he hated), where he briefly attended art school, before moving to Philadelphia to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. ‘Philadelphia is my greatest influence’, stated Lynch, noting that is ‘was a fear-ridden place’ and that he ‘saw many strange things’.

One was of understanding these strange things was through the art of painters like Francis Bacon, whose smeared and smudged figures seemed to epitomise the bleakness and nihilism of contemporary life whilst still capturing the essence of specific figures in portraits or juxtaposing minimal furniture and empty rooms in huge triptychs populated by awkward, fluid characters. Something about the dynamics of Bacon’s and others’ art seemed to have affected Lynch’s creativity, because he decided he wanted to make moving paintings. So, short films it was. Surreal short films where Lynch drew on his subconscious and the seedier, darker side of city life.

At the beginning of the 1970s this would result in one of Lynch’s most disturbing and original films: Eraserhead. It was dark (literally), creepy, with a lead character who seemed totally lost and whose hair stood up vertically, and a soundtrack of industrial noise and clanking machinery occasionally punctuated by saccharine songs. Its abnormal baby prefigured Alien’s stomach-destroying birth scene, and although it mostly got panned on release it has remained cult viewing since its initial release. Huddleston places it in a tradition of surreal film populated by the likes of Cocteau and Man Ray, whilst Lynch simply stated that ‘The world in the film is a created one’. Having taken up Transcendental Meditation (TM) during the production process, Huddleston notes how the TM ‘idea of blissful transcendence’ enabled Lynch to conclude Eraserhead with what Lynch regarded as a happy ending, facilitated by the singing Lady in the Radiator. It also provided both an alternative to and a lens through which to see the dark and unsettling worlds that Lynch would depict in his future works.

In The Elephant Man Lynch was able to humanise the grotesque John Merrick, who was a Victorian medical freak, making a quirky mainstream period drama in London through a major film studio. Informed by the quirky photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin, which frequently depict arrangements of cadavers, freaks, masks and other props, in scenes of sadism, sexuality, nudity and self-harm, Lynch explored questions about death and being human, as well as making his own photo series of Distorted Nudes.

And then it was on to Dune, a mainstream film that for some reason got critically panned although I am one of those who thinks unreasonably so. (See my chapter ‘David Lynch Constrained on Dune’ in A Critical Companion to David Lynch.) It may not match the sheer spectacle of the more recent Denis Villeneuve version or the giant spectacle planned by Jodorowsky in his unreleased 14-hour film, but it does capture the sheer oddness and otherness of Herbert’s worlds, and does not hold back on the violence and abuse of religion and power that Dune is all about. At the time, however, it was deemed a failure, mostly in retrospect from what appears to be studio interference and artistic compromise, and Lynch retreated home to Virginia. ‘“That experience could have finished me,” he said later. “It was so horrible. I identify so much with my films – and I knew I sold out.”’ He never would again.

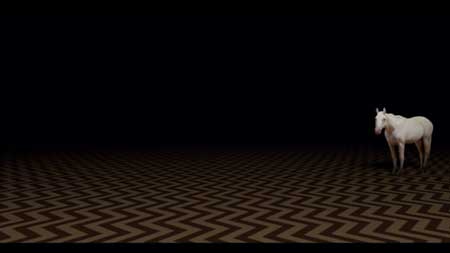

First there was the violence, sexuality and sheer deviance of Blue Velvet, a film that revealed the beautiful yet sordid underbelly of smalltown America in glorious saturated colour, then there was Twin Peaks, which did the same but in many ways appeared to be a much more normal and friendly place, one populated by pretty girls in tight knit sweaters, good looking clean cut boys, and wholesome parents, all watched over by a group of friendly local cops and visiting FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper. Tangled stories of sexual abuse, murder, prostitution, other worlds and occult knowledge, set up in contrast to everyday life, slowly wound viewers in throughout its first series and ensured they returned for Series 2. But then Lynch was told by the TV company to reveal the murderer earlier than he had planned, and to provide a closing finale for the whole series. The reveal of who murderous spirit Bob inhabited was a television highlight, but following that the series dragged, picking up and then abandoning a number of irrelevant and incidental storylines before a downbeat finale that saw Cooper trapped in the other world whilst a demon moved into his worldly body. And that, we all thought, was that.

It wasn’t of course. After Wild At Heart, a cinematic version of Barry Gifford’s book in which Lynch ‘saw a love story in a violent and insane world’, a film I find almost unwatchable, there was a Twin Peaks film prequel, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, where all the small town niceties of the TV version were trampled on and almost every character was revealed to be twisted and corrupt and/or complicit in the prostitution and murder that was supposedly the motivation for the original series. So, it was out with the coffee and donuts and 1950s nostalgia and in with deviance, lust and evil; and also, knives out for the critics and audiences, even those – like me – who loved the TV version. Never had the rug been so systematically and deliberately pulled out from under the fans.

It took many years and several other Lynch films before Fire Walk With Me got critically reconsidered and praised, but in the meantime we got a string of marvellous unsettling films: Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire all continued Lynch’s exploration of other worlds, but they also contained some kind of redemption or least an idea or underpinning of ‘blissful transcendence’. Lynch suggests that ‘People coming out of darkness visually is beautiful, but the idea of coming out of darkness is really what life is about’, an apt quotation on so many levels. Lynch constantly uses dark entrances, exits and hallways, and strange backgrounds as well as high contrast juxtapositions of night & day, the desert and the urban, the seen and unseen, similarity and difference… Are the two main characters in Inland Empire doubles or changelings, transformed spirits, or is one the dream of another? Perhaps all of those things. Lynch knows ‘that there’s much more going on than we can see, feel, touch… smell, hear, taste or kick.’

Through the middle of these films came The Straight Story, a film about a road trip an old man takes on a lawnmower. Responding to ‘the purity of the story’, Lynch made a straightforward and intimate story ‘about a man, all alone.’ It’s also, of course, about a man out of both time and place, just as Eraserhead and The Elephant Man were, but there is little or no horror or surprises, secrets or shocks in the film. It is what it is, it is what it claims to be.

Which Twin Peaks: The Return most definitely was not. Whilst not as unsettling or upsetting as Fire Walk With Me, The Return was a different version of Twin Peaks. Not only had 25 years passed onscreen as well as in our world, this third series was imagined as an 18 hour film shown week by week, one hour at a time. There were initially few returning characters, and Lynch upped the mysterious, revealing several portals to other worlds, doppelgängers, gods, demons and spirit beings, criminal gangs and alien spaceships, all seemingly connected through electricity wires and pylons, or perhaps the music and songs played (live each week) at The Roadhouse. Agent Cooper was for many weeks two people, both a simpleton and a violent thug, whilst many other characters appeared and left with no effect on the story being told, and then part 8 arrived. The ‘Gotta Light’ episode made for riveting viewing as it revealed the origin story of evil in the Twin Peaks world. The Atomic Bomb, mutated bugs, a giant, floating orbs, a romantic tryst, and The Woodsmen taking over a local radio transmission, all appeared to offer some kind of back story and some kind of resolution… if only we could grasp it.

It didn’t of course, any more than two tie-in books or the final few episodes of the series did. There appeared to be no happy ending, just a warning to Agent Cooper and perhaps viewers that we cannot meddle with time or change the consequences of other people’s actions. Cooper may have found himself and escaped from The Black Lodge but the psychic and physical fallout from the murders in series 1 and 2 remained in place, despite some characters seemingly living happily ever after, others going missing, or possibly simply have a mental breakdown and appearing out of dramatic or real time in the new series. The earth-shattering scream that ended the third series, the disappearance of Diane, Cooper’s secretary and lover, along with an abundance of irrelevant clues and abandoned scenarios gave viewers no sense of closure, only triggered more questions, just as art should.

Huddleston is adept at contextualisation and making his own links between Lynch’s various projects. Unlike me, he explores how Lynch uses music (both as soundtrack and as performances within films) to create mood, supply information and set the scene; considers Lynch’s video work, music albums and fine art; and steps back to consider the wider context of Lynch’s work. He regards Twin Peaks: The Return as a kind of bringing together of themes and ideas, a work of ‘unvarnished reality’ where Lynch ‘offers scenes of deprivation and poverty, trailer parks and cheap housing developments, crimes of desperation and need rather than simply of passion.’

I also need to point out that David Lynch. His Work, His World is amply illustrated, and is also that rare beast, a book that successfully treads the line between coffee table and intelligent non-fiction, being both highly readable but also full of information, facts and intelligent summaries and critical opinions. Although the book serves as a celebration and valediction of both Lynch’s life and artistic output, it is also a reminder that ‘Lynch’s work always venerated emotion and mistrusted words’. Whilst tributes such as Kyle MacLahlan’s ‘David was in tune with the universe’ seem mawkish and silly to this cynic, I can’t disagree with Huddleston when (with regard to Twin Peaks: The Return but I think applicable in a wider sense) he asks ‘what better place to end than a full-throated, heart-shattering scream of absolute confusion and terror?’

It would be disingenuous of me to suggest that Huddleston’s book is heart-shattering, confused or terrifying, but it does take on the challenges of trying to articulate the why and how David Lynch worked and start to understand what (on earth) he made. Huddleston is not wrong when he notes that The Return ‘at times felt […] like a swansong. Intense, baffling, heartbreaking, hysterical and wild.’ As long as that hysteria and wildness includes humour and the unexpected that will do me as a summation of the marvellous work that Lynch made and Huddleston helps immortalise here.

.

Rupert Loydell

.