WE HAVE taken a definite interest in the Liverpool Poets with Rock and the Beat Generation carrying a review of a Roger McGough live show in 2021 and a special tribute to Adrian Henri’s wonderful poem ‘Me’ the following year.

Both writers displayed interesting musical allegiances. McGough moved from page to stage when the Scaffold, the comic cabaret group he co-formed, enjoyed Top 40 success. Henri formed the Liverpool Scene and then GRIMMS, bands which interwove rock, blues and jazz with the spoken word.

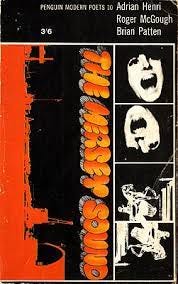

Alongside their younger collaborator Brian Patten, the trio were fêted from the early 1960s, initially in their home city of Liverpool and then much more widely when, in 1967, the famed Penguin Modern Poets series released a volume entitled The Mersey Sound projecting their verse work to a much wider public. It became the biggest-selling UK poetry anthology of all time.

Patten’s relationship with the musical world was more ambivalent though he did participate at times with GRIMMS and some other ensembles. Departing the intense urban noisescape of Liverpool in the same year as The Mersey Sound was published when he was only 21, his main focus for 50 years and more has been his poetry, with close to 30 collections for both adults and children published to date.

R&BG was keen to explore the impact of music on Patten’s life and work but, in an exclusive interview with contributor MALCOLM PAUL, the poet shared his thoughts on that and many matters besides: the Beats and other poetic influences, the Merseybeat explosion, the Cavern and initially, another passion in his life, gardening…

Sorry, Brian, for not getting back sooner. The main reason: I had necessary garden tasks to complete and I think I have more chance of winning a Nobel Prize for Physics than ever being an accomplished gardener!

Hello Malcolm. Even if you don’t do gardens you are obviously a good bloke so here goes: some responses to your questions…

Thoughts on gardening first. I had a poet’s garden in an earlier place I lived. Bits of cuttings and seeds I could bring on. Plumbago from Robert Graves’ garden, poppies from the garden of the house William Wordsworth had in the Lake District, geraniums from Lorca’s museum on the edge of Granada and so on.

So Brian, when did you first come into contact with the Beats? Was this with Roger McGough, Adrian Henri, Liverpool in the Sixties and all that, the Beatle era and Allen Ginsberg declaring that ‘Liverpool was the centre of the consciousness of the human universe’?

No, I got hold of a copy of Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ a few months before I met Roger and Adrian. We, like many poets, were enthused by Allan Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Robert Creeley, etc., and, over time, met and read with them.

But our influences were other people: the likes of Prévert, Rimbaud, ee cummings, the French surrealist poets and Lorca. For me, at 15 and 16 years old, Rimbaud especially. He was outside it all. Incidentally, Allen saying ‘Liverpool was the centre of the consciousness of the human universe’ was nothing new. He probably said the same thing about Milwaukee.

When did you first meet the others, Roger and Adrian? What were they doing artistically?

I met Adrian and Roger when I was 15. I’d been out of school a few weeks and was already writing poetry. At the time Adrian didn’t consider himself a poet. He was first and foremost a painter. I love his work.

Any particular stand out memory of the Beats?

Mysticism, jazz, etc. were not on my radar, though of course the Beats were liberating personally. First reading ‘Howl’ took my breath away, such rawness.

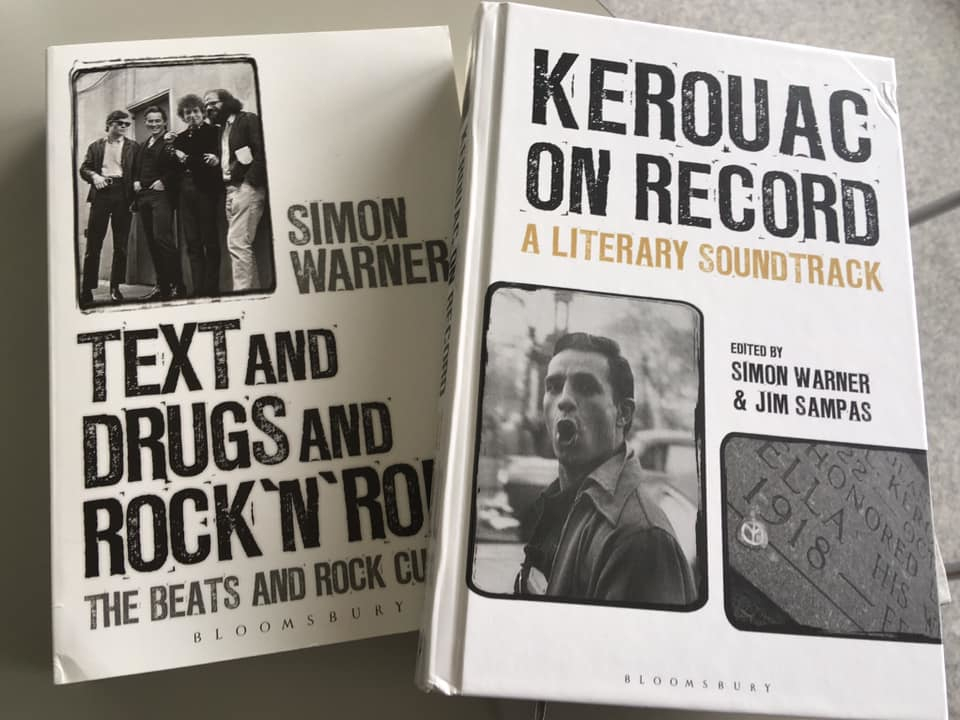

Pictured above: The Liverpool Poets…Brian Patten, Adrian Henri and Roger McGough with River Mersey in view

Did you think poetry was being communicated in a different way back then? Perhaps with a bit of help from the radical immediacy and simpler writing approach of the Beats?

I would say that our language was common speech and our audience in the early days were not really students, but the working young. They would come to our gigs one night and go to the Cavern the next. We even did occasional gigs at the Cavern ourselves.

Can you talk a bit about your experience with music at the time you were in Liverpool.. in the days of the Cavern and attempts to weld music and the spoken word together? Do think it was a successful experiment?

Bob Wooler, DJ at the Cavern, tried to get me to record poetry and music – he even got a group of musicians together and managed to record a few things when the place was empty. But my heart wasn’t in it. I felt something of a dickhead standing in front of these musicians mouthing away. I was young, and poetry was my passion.

Could you talk a bit about other musical projects you were involved in and some of the people you enjoyed working with…

I did a few things later with special friends, mostly Andy Roberts and the very much missed Neil Innes, but overall the music I’ve found is in the words. I felt the poems did not need embellishments. Not that I didn’t love the music.

As a 15, 16, 17 year old in Liverpool my favourite groups were the Clayton Squares and the Roadrunners, and I was happy standing at the back of the venue soaking up that musical energy – it was glorious, not just the music but the atmosphere, being there in the moment, , the communality of it.

What about the magazine you published?

That was my little mag Underdog – it published many of the poems by the three of us that ended up some years later in The Mersey Sound. New work by Allen and Adrian Mitchell also figured in later editions. I also wrote occasional new pieces for a short-lived magazine that was a little like Liverpool’s main music paper Mersey Beat and was called Combo. I was 21 when Penguin Books published The Mersey Sound. I decided to leave Liverpool the same year, before I drowned in the media onslaught.

Pictured above: The original edition of The Mersey Sound from 1967

What happened next? Any memories you would like to share ?

I wanted to go off and write in peace and ended up in Winchester. There was a great calmness about the place. I shared a house for a while with Brian Eno, who was at art college.

In the 1980s I was over in Deià in Spain and often stayed with Kevin Ayers in his huge casa. Downstairs the kitchen was always in shadows and upstairs the bedrooms were empty but for mattresses on the floor. Also I made various sideways contributions to some of his later songs.

We would sit up late at night in the courtyard swapping ideas and lines. He loved a line of mine in a poem I wrote while staying with him called ‘The Ambush’. The line was ‘Falling heavenward’ and his last album was Falling Upwards. I think what we had in common was best expressed in his song ‘Am I Really Marcel’.

Any particular tracks that you would to highlight where you have had poems performed to music, maybe a few you can mention?

Cleo Laine sang a poem of mine on an LP she made with John Williams. I also made the LP Vanishing Trick, on one side of which was me reading my poems and on the other people singing my lyrics/poems.

Mike Westbrook wrote music for a poem called ‘Embroidered Butterflies’ which was sung by Linda Thompson, with Richard Thompson on guitar and John Taylor on electric piano.

A poem of mine ‘Sometimes It Happens’ was also sung by Linda Thompson, which she particularly loved and featured prominently on her own compilations, Dreams Fly Away and Give Me A Sad Song.

Others were ‘You Missed the Sunflowers at their Height’, with music by Andy Roberts, sung by Linda with Andy Roberts on guitar, Neil Innes on piano & organ, Dave Richards on bass and drummer Gerry Conway.

Music has clearly been a muse for you both as a listener and a participant.

May I just ask a few more questions about, say, jazz? The Beats loved bebop. Did you listen to jazz, especially bebop?

No. Adrian Henri was into jazz. I much preferred the Stones to the Beatles in the very early days..

You never struck me as a person or poet who wanted to be in anyone’s group despite possible common interests.

That’s true enough. But the label ‘Liverpool Poets’ stuck to the three of us and, only later on in life, did I think how useful some labels can be. Without them you don’t know what’s in the can.

You came across to me as being relentless in looking for new ways forward. The poems improved with age?

I met Roger and Adrian when I was 15 and had been writing for two years by then. I do think each of my books have improved. The first contained some juvenilia, as did the second. But I guess I was lucky in that some of those early poems still seem relevant.

Still perfecting your craft?

I’m still writing and am putting together a new collection of poetry, and a memoir. But I do not write poetry in order to publish them in a book. That is secondary. Years ago I moved to Devon, and grew less and less involved in the scene.

Do you feel you have found peace now ?

Not a peace no, it’s something else.

I personally see it in your recent work…a calmness. How important did rebellion, ideas of anti-establishment, influence your life and work as it did the Beats?

Every generation rebels against the one before. It is necessary. One only hopes our best poems survive. The literary critics of the time hated us when we first published. Their reviews were littered with poison. ‘The three legged pantomime horse’, one said. ‘They write for the great unwashed’, said another. And on and on.

Do you still think there is a role for a counterculture in our modern society, the challenges different but just as great? And do you look back and think how lucky you were to have been at the centre of a cultural earthquake and seismic change that opened the door for poets like me and thousands of others. made poetry something the ordinary working class man and women could be part of together?

Yep.

Thank you Brian for your time and sharing so many memories. I hope the information you provided will be a source of future research….

It’s been a pleasure sharing, Malcolm.

See also: ‘“Me 2” by Simon Warner’, October 15th, 2022; ‘“Me” by Adrian Henri’, October 15th, 2022; and ‘Live review #1: Roger McGough’, October 23rd, 2021

Originally Published in https://simonwarner.substack.com