The famous painter waits in the wings of the main stage. ‘I know my stuff, and I’m famous,’ he mutters to no one in particular. His interviewer is famous too, what with his yard of books and own TV series. He was known as passionate, principled. He’d gone on about it in the green room, before his coda, ‘but we’re here to talk about you, Sir Stanley,’ the emphasis on the Sir – before genuflecting.

‘Oh humph,’ he’d said, every bit the knighted yet humble painter, ‘you’ll be offered one in a few years.’

‘I like to think I’d turn it…’ The famous presenter had swallowed the word ‘down’ before it could leave his mouth. He’d gone an interesting pink – flake white mixed with a smear of viridian red. What a study, he’ll remember that.

‘I have one of your canvases over the mantelpiece at home,’ Mr Turn It Down had said.

‘Oh? Which one?’

‘Er, untitled.’

‘What dyer pay for it?’ he’d asked, knowing that it was Glad Morning in Uttar Pradesh.

‘Thousands.’

An usher comes, a local sixth former, in love with all writers and painters, her hair brushed back, eyes gleaming. Another interesting study, he thinks. Then the presenter is at his elbow, and onto the stage they go, pushing their fame before them, each trying not to trip over the coils of camera wire. They settle to an extended pitter-patter of applause, like rain on the canvas walls. Broad smiles beam up at them, sideways smiles, heads cocked, some of them clapping their hands above their heads. A man stands in salute but no one follows him, so he sits down, flushed. Flushed is interesting, he thinks, the red mixed into the white would need to be maroon, the white a Titanium to give it that edge.

A hush descends upon the marquee, and he sees the grey eye of the monster, behind it, its mistress the camerawoman, her hat the wrong way round, tendrils of fair hair escaping. He thinks of Medusa.

My esteemed guest needs no introduction,’ says his interrogator.

So he doesn’t get one. He notices a few punters consulting their programmes. Ha! Notices too that all the faces are what his old friend EM Forster called pinko grey. What a good name for a colour, he thinks. They should sell it in tubes.

He studies the diffused light bleeding like tinted steam through the walls, trying to name its colour, or is it a hue?

He hears the first question loudly, too loudly. Of course, it’s the second time of asking. ‘Describe your processes, Sir Stanley.’

‘Er,’ he replies, and studies the sharp viridian green stain on his white shoe – a rather fine mottled smear from the damp spring grass outside, as grinning loons approached him with pieces of paper for his autograph, a white space at the top for a squiggle, a sketch even. He’d obliged, even though his gallery had asked him not to.

‘OK,’ says Turn it Down, ‘the paintings seem spontaneous, not consciously thought about.’

What twaddle, he thinks, everything is a dance between the Dilly and the Dally, his names for his conscious and unconscious minds. But he says instead.

‘No.’

‘Oh.’

The crowd grows restless, a few rictus grins, faces fanned by programmes. The eye of the camera is steady, the camerawoman smiling. She doesn’t care, he thinks. She just wants her lunch. But that bloody eye doesn’t blink – a milky but opaque grey, an oblong hood around it like a cobra ready to strike at the centre of him. The camerawoman’s knee jiggles in her sage green combats.

‘Are you comfortable Sir Stanley?’ asks Turn It Down, his voice a tad higher.

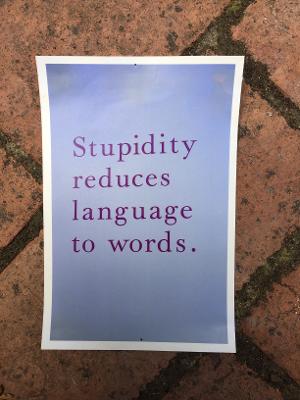

‘Yes!’ He doesn’t mean to snap but maybe it will release the flow of trapped words. Remove the dam at his tongue. Maybe the words will melt and come trickling out in a sweet flow of art talk, words like voluble, sensual, colour-tension. Some of them slight enough to squeeze through his teeth – bold, thick, thin – or oblong words like motivation, creative processes, non- figurative. Round, plump ones – ellipse, circle, blob. But they clog his mouth, a pallet of unspoken colour straight from the tube, some leaking into turds of white. The words also smell, of linseed oil, turpentine, and fixative. But that dull grey eye keeps them locked away. ‘Our time is up,’ says Turn It Down. ‘Have you anything else to say, Sir Stanley?’

‘No,’ he says, feeling that the eye might be his friend after all, deciding to ask the camerawoman to lunch to ask her what she saw.

.

Jan Woolf

Painting: Ian Hamilton Finlay