Considered by many one of the founding texts of the science fiction genre, The Blazing World — via a dizzy mix of animal-human hybrids, Immaterial Spirits, and burning foes — tells of a woman’s absolute rule as Empress over a parallel planet. Emily Lord Fransee reflects on what the book and its author Margaret Cavendish (one of the first women to publish using her own name) can teach us about empire, gender, and imagination in the seventeenth century.

It is the middle of the seventeenth century and a Bear-man is helping an empress attempt to examine a whale through a microscope. After this task is found to be impossible, a group of Worm-men explain how creatures can exist without blood and how cheese turns to maggots. In her turn, the empress scolds an assembly of Ape- and Lice-men for their pursuit of tedious and irrelevant knowledge, such as the true weight of air, and commands they instead get busy with “such Experiments as may be beneficial to the publick”. Armed with such knowledge of the natural world and equipped with the resources of her vast dominions, she then sends flocks of Bird-men and navies of Fish-men to a parallel planet to make war on and conquer her many enemies.

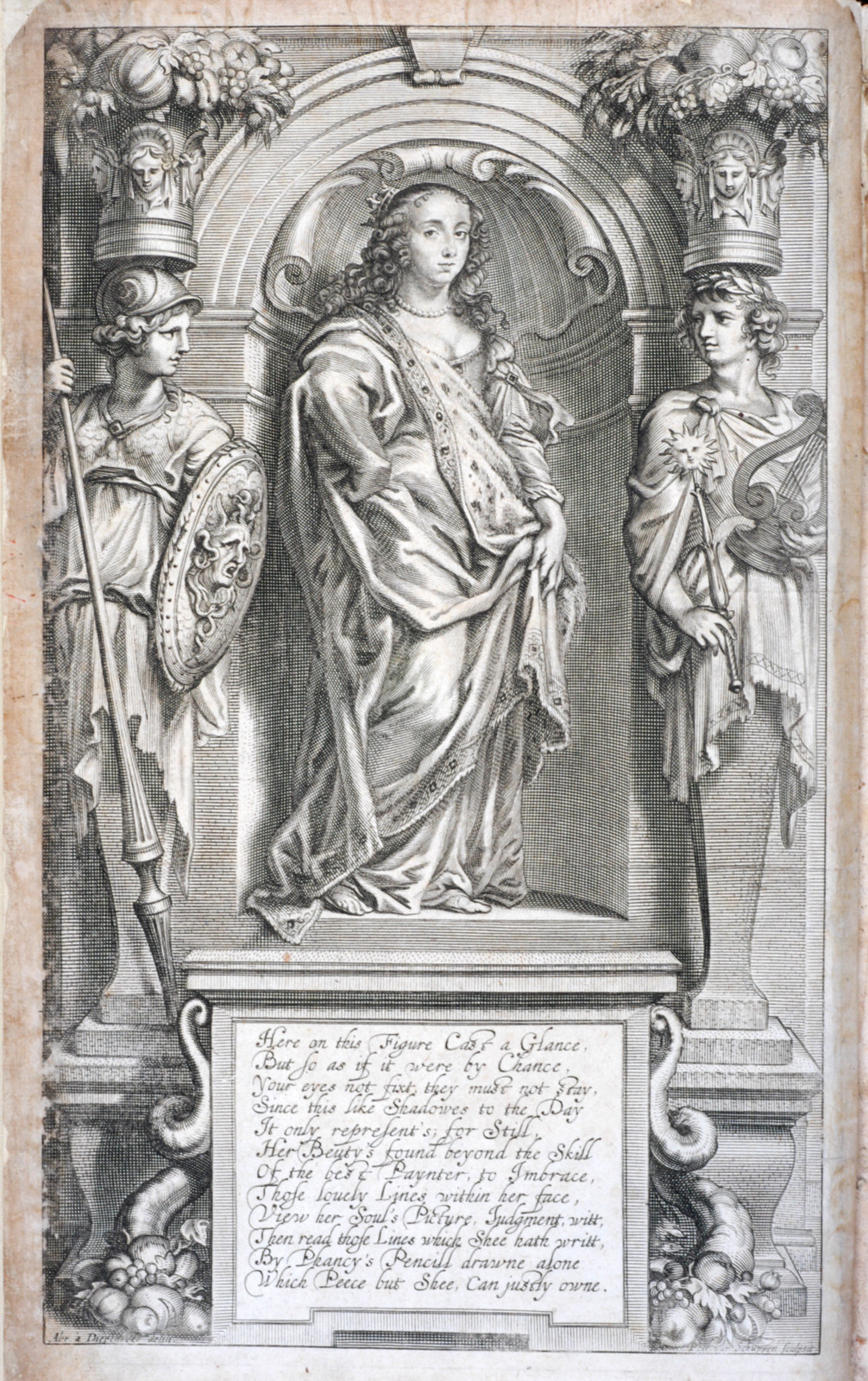

Such are the links between life, learning, and power within The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World, a piece of prose fiction published in 1666 by the “Thrice Noble, Illustrious, and Excellent Princesse the Duchess of Newcastle”, better known as Margaret Lucas Cavendish. The narrative blends utopian fiction, imperialist travelogue, and natural history to tell the story of a “young Lady” who is kidnapped from her homeland but soon escapes to a new and mysterious land filled with human-animal hybrids. On arrival she is made empress and quickly establishes societies of natural philosophy, funds theater and the arts, and destroys her enemies with fire and fury.

The plot is often convoluted, with descriptions of military invasion or discussions with fantastical chimeras interspaced with short lessons on lenses or lectures on the nature of solar eclipses. Yet there is much that can be learned from Cavendish’s Blazing World, including the way it sheds historical and literary light on conceptions of gender, natural philosophy, political theory, theology, and the life of the author herself in seventeenth-century Europe. For example, in the emphasis on the stability of a realm in which everyone —- from the lowest Flea-man to the highest Emperor —- knows and respects their place in the natural hierarchy, we can see echoed Cavendish’s Royalist sympathies. Histories of feminism have also mined Cavendish’s works, as they reveal the ways in which she saw her own position limited within a society shaped by both gender and class. However, less examined is the way that the narrative illuminates the history of seventeenth-century European imperialism, and how ideas about power, race, and conquest related to those of gender and knowledge.

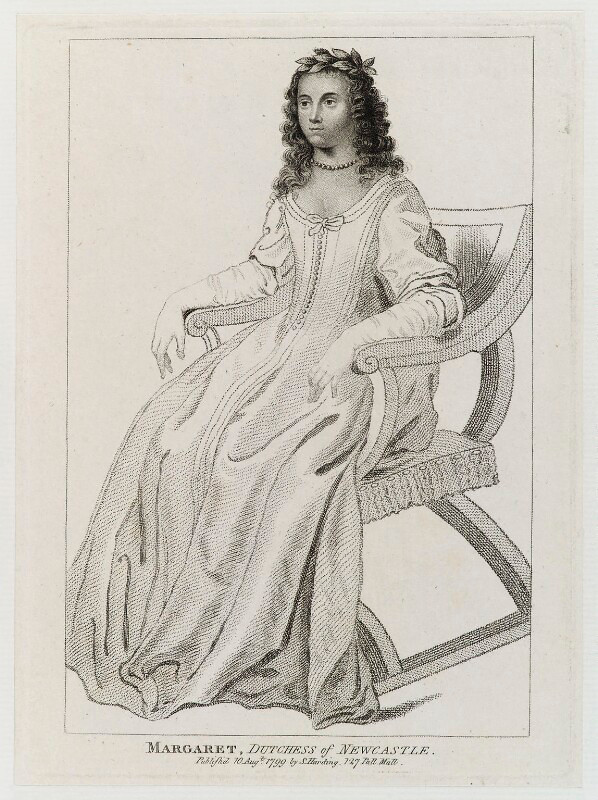

In considering the imperialist resonances of The Blazing World, it is helpful to start with Cavendish herself, an aristocratic philosopher poet whose reputation was divisive while she was still alive. A brief look at her published works indicates the range of her intellectual interests: poetry collections, a play entitled A Comedy of the Apocryphal Ladies, and scientific works such as Observations on Experimental Philosophy (1666), the latter of which originally included The Blazing World as an appendix of sorts. She was the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, where the all-male assembly protested her very presence. Of her visit, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that she was a “good comely woman; but her dress so antic and her deportment so unordinary, that I do not like her at all, nor did I hear her say anything that was worth hearing.”1 Her unusual wardrobe was a frequent focus of society commentary, cropping up again in English writer John Evelyn’s recollection of a visit to the Duchess that left him “much pleased with [her] extraordinary fanciful habit, garb, and discourse”, as well as her “extravagant humour and dress, which is very singular.”2 Her “singular” clothing choices played with conceptions of gender as well: her penchant for masculine waistcoats contrasting with one notable incident in which she addressed the audience at one of her husband’s plays while wearing a self-designed dress based on ancient Cretan costumes that left her breasts “all laid out to view.”3

While her intellectual achievements were distinctive in and of themselves, Cavendish’s iconoclastic behavior maintained her reputation as an eccentric contrarian, earning her the nickname of “Mad Madge”. After meeting her in London, for example, one contemporary described her conversation as “airy, empty, whimsical, and rambling as her books, aiming at science, difficulties, high notions, terminating commonly in nonsense, oaths, and obscenity.” During their time together, Margaret reportedly claimed a place among the intellectual greats, declaring that “if the schools did not banish Aristotle, and read Margaret, Duchess of Newcastle, they did her wrong, and deserved to be utterly abolished.”4 This characterization of Cavendish as an idiosyncratic and unseemly egotist was echoed many years later in A Room of One’s Own, where Virginia Woolf describes her writings as a “vision of loneliness and riot . . . as if some giant cucumber had spread itself over all the roses and carnations in the garden and choked them to death.”5

The Blazing World provides a semi-autobiographical counterpoint to this characterization, not only in the insertion of Cavendish herself as a wise and respected character, but also in her depiction of the main protagonist the Empress as an intelligent woman whose ambition enables her to thrive in the isolated world that she rules absolutely. From this perspective, the self-important dilettante who forces her unwanted opinions onto others transforms into a besieged heroine who champions her own independence and intellect in a society that fails to appreciate her achievements. Lengthy passages describing intellectual life within the Blazing World take on greater significance when seen as critiques of the tediousness and limits of Cavendish’s own experiences within the male-dominated “learned society” of her day, as well as reflect her advocacy of self-expression and freedom from revision (she once wrote that she had “neither Room nor Time for such inferior Considerations” as “Mending or Correcting” her writings.)6

The Blazing World also fits into a larger body of speculative and proto-science fiction works of seventeenth-century natural philosophy, imagined terrestrial and cosmic voyages that sketched out new conceptions of the operation of life and the universe. Even in post-Copernican Europe, such speculation could be seen as dangerous and heretical. In 1600, Italian astronomer Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for his claim that the universe was infinite and contained innumerable worlds, essentially killed for arguing in favor of free imaginative speculation in the service of knowledge.7 By the mid-seventeenth century, imaginative works about the operation of the universe became more widespread (and less hazardous to publish) as men such as Johannes Kepler, Francis Godwin, and Cyrano de Bergerac used cosmic voyages and utopian narratives to consider humanity’s place and significance in time and space.

In a context of ongoing religious reformation, many of these narratives centered on theological questions such as the primacy of Christ’s Earth-bound sacrifice in a potentially infinite universe, as narrators describe meetings with a variety of “exotic” beings from human-animal hybrids to moon people to the political elite of advanced utopias. Such confrontations raised questions about who (or “what”) could or could not be saved within a Christian worldview. This preoccupation with fictionalized “otherness” was of course intimately related to European efforts to map, colonize, and profit from various regions of the globe. Such a context gives significance to plot points that might otherwise seem bizarre or inexplicable. Read in connection with the violent history of European conquest in the Americas, for example, theological discussions about whether or not lunar beings could be saved from damnation become reworkings of contemporaneous debates about the fate of “unsaved heathens” living in the “New World”.8 With a consistent emphasis on exploration and alterity, such speculative fiction can be understood as the literary imaginary of imperialism, often (although not always) appearing as a celebration of scientific advancement in the service of conquest in imagined new locations.

In many ways, The Blazing World is similar to other speculative works from the seventeenth century, particularly in this connection between imagined and real “new worlds”. In his loving dedication, Cavendish’s husband William Newcastle makes this connection explicit, describing his wife’s narrative as a fictionalized “Fancy” made of “Nothing, but pure Wit” that mirrored the “discoveries” of Columbus, who “found a new World, America ‘tis nam’d”. However, unlike many of her contemporaries, Cavendish creates a new world in which the “discoveries” are made by a woman. Within her own realms of “Fancy”, the Empress is free from the gendered limits of the author’s own world — she acts as she wishes and her people adore her all the more for it. Indeed, throughout the narrative of The Blazing World, the female characters are celebrated for their political, territorial, and intellectual conquests, even (or especially) when they entail great violence.

Shortly after our introduction to the unnamed female protagonist, she “discovers” a new land when she is “forced into another World” that is joined to her own near the North Pole. Alone and fearful for her life in this strange new place, she is rescued by a large assembly of Bear-men who carry her to their city of underground caves. She quickly becomes the subject of reverence, as “both Males and Females, young and old, flockt together to see this Lady, holding up their Paws in admiration” and decide to “make her a Present to the Emperor of their World”. On their journey to the royal city where the “Imperial Race” is said to dwell, she meets up with the other indigenous subjects of the Blazing World, including Fox-, Geese- and Bird-men, Satyrs, and “men of a Grass-Green Complexion”. The newcomer learns the local language and observes remarkable technologies, including a ship powered by the “extraordinary Art” of a “certain Engin” which operated by drawing in and expelling a “great quantity of Air” that could act as a motor and cut a path of tranquility through rough waters.

Upon her introduction to the royal court, the outsider’s beauty and radiance convinces the Emperor that she is “some Goddess” to be worshipped, wed, and crowned. The Emperor seemingly brushed aside, the woman now has “absolute power to rule and govern all that World as she pleased”. To exemplify her new station, the now-Empress dons an impressive outfit of bejeweled clothing and accessories that make use of local natural resources to better reflect her political power. Along with a “Rain-bow” colored diamond-encrusted “Buckler, to signifie the Defence of her Dominion”, she also wields a “Spear made of white Diamond, cut like the tail of a Blazing Star, which signified that she was ready to assault those that proved her Enemies.” Making quick use of her new authority, the Empress establishes “learned societies” to ensure that all of her animal-human subjects “followed such a profession as was most proper for the nature of their Species”, be that philosophy, astronomy, chemistry, physics, politics, mathematics, oration, or architecture. Natural hierarchies are thus maintained and every Satyr and Fox-man knows their own place in the cosmic order.

Following a lengthy account of reform (and counter-reform) of intellectual life within her vast dominion, the Empress turns to religious and spiritual matters, collaborating with “Immaterial Spirit” beings to create her own “poetical or Romantical Cabbala” and, in the process, summoning the soul of the Duchess of Newcastle Margaret Cavendish to act as her personal scribe. Although the two are from different “Home Worlds”, the two authorial ciphers soon become close friends in the Blazing World, particularly due to their shared ambitions for glory and power. The Duchess (as the character of Margaret Cavendish is referred to in the narrative) soon becomes upset that she has no empire to call her own, leading the two to discuss how she might acquire such a dominion. After deciding that “terrestrial” conquest will not suit her needs, the Duchess is advised by the Immaterial Spirits to simply write her own “Coelestial World . . . for every human Creature can create an Immaterial World fully inhabited by Immaterial Creatures, and populous of Immaterial subjects . . . and all this within the compass of the head or scull”. In creating her own world according to her own rules, she may enjoy her power “without controle or opposition”, making “what World you please” that can be altered and enjoyed without limits.

However, their joyful celebration of the possibilities of speculative fiction are cut short when the Empress learns that the place of her birth has come under attack. Mobilizing the vast intellectual and material resources of her new dominion, she vows revenge and promises “all the assistance which the Blazing-World was able to afford”. To most efficiently mobilize troops, the Emperor suggests that the Immaterial Spirits might be able to inhabit the bodies of their dead foes. The Empress, however, argues that such a thing would “never do” as they’d struggle to acquire so many corpses in the first place, and besides, in the rough and tumble of battle, they’d simply “[moulder] into dust and ashes, and so leave the purer Immaterial Spirits naked”. An army of the walking dead ruled out, it is decided, upon the Duchess’ suggestion, that the Bird-men and Fish-men will lead the vanguard, taking to the sky and the sea to initiate the attack. Giants (the architects of the Blazing World) are commissioned to devise new modes of water transport in the form of golden “Ships that could swim under Water” and better bring their troops to battle. Worm-men are sent out to amass huge amounts of “fire-stone”, a “Greek fire” type of material that burned when wet and therefore could not be quenched.

The invasion is a violent success. After establishing the king of her former homeland as the “absolute Master of the Seas, and consequently of that World”, the Empress watches for any sign of dissent, punishing those who try to escape payment of tribute by bringing “fire [to] all their Towns and Cities” and warning those who would cross her that “if they continued still in their Obstinate Resolutions, that she would convert their smaller Loss into a Total Ruin.” After pulling the ships back underwater and returning to the Blazing World, the Empress and Duchess content themselves with their works and deeds, secure in their ability to express their intellect and broadcast their political power.

Depictions of conquest in spectacular and science fiction remained popular with European audiences from the seventeenth century onward. Haunted by imperialism as they are, these stories can act as a useful tool for understanding how such ideologies have shaped the past and present. At the same time, works like The Blazing World do have their limits in this respect, as most reflect very little on the perspectives of those forced into colonial subjecthood. In more recent years, indigenous futurism and other postcolonial science fiction have changed this situation, as writers, filmmakers, and artists use the genre to critique the history and legacies of imperialism.9 While science fiction and empire are historically linked, the relationship is flexible and ever-changing.

The imperialist presence in Margaret Cavendish’s Blazing World itself is not a simple one. Her drive, through the character of the Empress, to conquer and exert power in her imaginary realm — this “New World” all of her own — seems a response to real-world limitations she encountered as a woman in the seventeenth century, albeit ones specific to the privileged world of a Duchess. If imperialist ideology inhabits the genre of science fiction in the imagining of interstellar frontiers of masculine swagger, we see here it takes a more unexpected form — a speculative domain for a woman to express her otherwise bridled will, where she is not forbidden from the most learned scientific societies but instead creates them. Indeed, she encouraged others, particularly elite European women, to create their own fictional realms to fit their desires, be that the expression of thwarted political power or securing respect for one’s intellectual scientific prowess. In this, the character of the Empress mirrors that of the author, whose preface asserts her to be “as Ambitious as ever any of my Sex was, is, or can be”, and whose creation of worlds means that “though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second; yet, I will endeavor to be, Margaret the First: and, though I have neither Power, Time nor Occasion, to be a great Conqueror, like Alexander, or Cesar; yet, rather than not be Mistress of a World, since Fortune and the Fates would give me none, I have made One of my own.”

Emily Lord Fransee is a historian who studies colonialism, gender, citizenship, and science fiction. She recently completed her PhD in History at the University of Chicago and teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

1. Samuel Pepys, The Illustrated Pepys: Extracts from the Diary, ed. Robert Latham (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 144.

↩

2. John Evelyn, diary entry, 18 April 1667, cited in Charles Wells Moulton, The Library of Literary Criticism of English and American Authors, Volume II: 1639–1729 (New York: Henry Malkan,1910), 231.↩

3. Charles North to his father, 13 April 1667, cited in Tanya Caroline Wood, “Brave New Worlds? The Gender Politics of Margaret Cavendish’s Primary and Secondary Realms” (PhD Thesis, University of Toronto, 2001); and Katie Whitaker, “Duchess of scandal”, The Guardian, August 8, 2003, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/aug/08/gender.uk.

↩

4. The Home-Life of English Ladies in the XVII Century (London: Bell and Daldy, 1860), 79.↩

5. Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 47.↩

6. Sylvia Bowerbank, “The Spider’s Delight: Margaret Cavendish and the ‘Female’ Imagination”, English Literary Renaissance 14, no. 3 (1984): .↩

7. Adam Roberts, The History of Science Fiction (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).↩

8. For example, John Wilkins’ The Discovery of a World in the Moone, or, a Discourse Tending to Prove that ’tis Probable There May be Another Habitable World in that Planet (1638) ponders if non-Earthly life would also be “the seed of Adam” and therefore “liable to the same misery [of original sin] with us, out of which, perhaps, they were delivered by the same means as we, the death of Christ.” On histories of “native conversion”, see María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998); and N. P. Cushner, Why Have You Come Here? The Jesuits and the First Evangelization of Native America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).↩

9. While its popularity (or perhaps popular visibility) has grown in recent years, anti-colonial science fiction and speculative fiction is as old as the genre itself. Recent anthologies and overviews include Grace L. Dillon, ed., Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012); Fábio Fernandes and Djibril al-Ayad, eds., We See A Different Frontier: A Postcolonial Speculative Fiction Anthology (FutureFire.net Publishing, 2013); and Nalo Hopkinson, ed., So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction and Fantasy (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004).

https://publicdomainreview.org