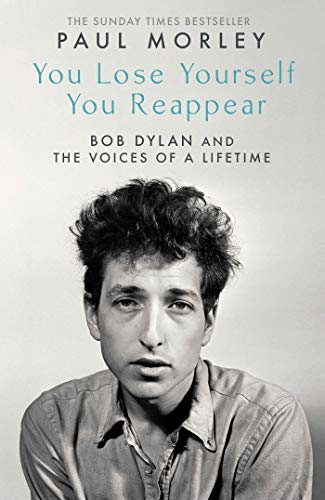

You Lose Yourself, You Reappear: The Many Voices of Bob Dylan, Paul Morley (400pp, £20, hbck, Simon & Schuster)

More than anything this book has reminded me that I don’t like Bob Dylan’s music very much. I seem to have a lot of CDs by him, but often when I take one down to play it gets swiftly taken out of the stereo and put back on the shelves. Take this morning, for instance: I sat in the sunshine outside with a cup of coffee and read Paul Morley’s take on ‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’. He made it sound so intriguing that I came inside and listened to it. What do I get? 11 minutes of nasal whine, with a few moments of nice organ.

Don’t get me wrong, I will listen to Desire and Blood on the Tracks anytime. And when I am in the mood the Bootleg Series of his gospel music is a knockout, making far more sense of this period of Dylan’s music than the original albums do. (I have had some awesome live bootlegs of the gospel shows for a long time.) But the ‘comeback’ stuff with Daniel Lanois producing? Nah. The original folk protest stuff? Nah. The recent surprise lockdown album released without warning? Nah, not really. Not today, anyway. Truth be told, not often.

Dylan is clearly an important part of musical history, there’s no question about that. And he’s on my shelves because I’m inclined to think of my music collection as a kind of library, which needs to cover the basics as much as the obscure and personal. But If I want singersongwriters I’d rather have Joni Mitchell or Laura Nyro, if I want protest I might go back to Woody Guthrie or root around in the Alan Lomax archive recordings. Some country songs? John Prine is the man, or maybe John Stewart. Dylan may have influenced some of these, may have borrowed from others, but somehow what he takes all becomes submerged into sounding like Dylan, and to these ears that is not good.

Morley’s book is, like all his books, as much about Paul Morley as his supposed subject. Here, he spends a lot of time wondering how to start the book, because his original plan was disrupted by Covid. It reminds me of Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller, every chapter opening up new directions from another possible start. Morley sees Dylan as a collection of voices, assumed for good reason: to suit the moment, the times, the songs, what is required, what his audience do or don’t want…

It’s a good way to think of Dylan’s work, and a good way to hang biography, stories and criticism on. It’s also a great way to generate lists, and Morley is an expert listmaker! Songs, names, influences and alternative ideas, sources and resources: you name it and Morley has a list for the reader. It’s Morley’s way of keeping his and our options open, of legitimising digression and tangent, of recognising that how we listen is dependent on what we know and when we listen, what we bring to the experience as much as what is present in the recording.

So Morley isn’t afraid to throw in ideas that on one level make no sense. There is no link between Borges and Dylan, yet once Morley has mentioned it it makes perfect sense. Much of the book is like this, outlandish and provocative ideas which, once you are over the shock and your instant response (‘Don’t be ridiculous’), make you think. And now there is a link between Borges and Dylan, because Morley has made it. It’s theoretical, unproven and conjectural, but why not?

I’m drawn to Morley’s writing because he isn’t definitive. I was brought up to see both sides of an argument as a way of understanding a topic, to debate as a critical tool; Morley obviously was too. He clearly loves Dylan’s music far more than I do, but is still prepared to argue with it, critique and question it, and to grapple with the burden of fame and literature it now carries. Then he moves on and starts another line of questioning or offers another set of answers. Each chapter here feels like an authorial riff, or series of riffs, that runs on for pages then stops, only for the author to change instrument and angle of attack and start up all over again in the next chapter. The writing, the words on the page, are as interesting as the content, evidencing Morley’s fluid, erratic, erudite and original mind.

More than anything this book has reminded me how much I like Paul Morley’s writing. Whatever he is writing about, even Bob Dylan.

Rupert Loydell