Necessary Animals make a case for escapism in latest LP – and that’s why I use their music in my films

By Bruno Decc

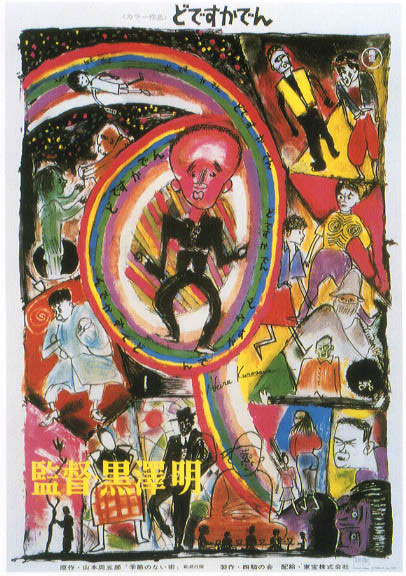

Poster for Akira Kurosawa’s film Dodes’ka-den, 1970

Necessary Animals, a multidisciplinary arts collective responsible for the oneiric high texture psych-pop pieces like Amarilla, just released a new set of tracks, Dark Jazz, turning for the moment to experimental jazz. If you haven’t checked it, please do, it’s brilliant.

Ingvild Syntropia & Keith Rodway from Necessary Animals

The content is deep, powerful and even primal at times. Music like You Took the South, I’ll Take the Twilight Skies feels like a journey into exotic places where you can reconnect with greater-than-yourself concepts.

If you don’t like experimental music – one that doesn’t necessarily focuses on pleasing you all the time and mixes in moments of disharmony as part of a process of enrichment and texture – maybe this won’t be for you.

But this is not only a band review. This new LP release got me to reflect more deeply on their music and my association with them in two recent works – the feature film Escape from Brazil and the web series Out-of-Place Artefact. What is it I find so fascinating and appealing about their craft?

It’s the feeling I get overall to listening to NA; being in a getaway car, escaping from a dark convoluted urban space, not desperate, but unsure of the future. The escape itself matters, it’s important to move even if we don’t know where to – all portrayed in a dreamlike, almost psychedelic way.

So it made sense that, when studying the same themes of escape and escapism for my feature film last year, I felt deeply connected to their music. Keith Rodway, band leader, would eventually lead me to more of his work that was also used in the films, but the pieces from NA maintained that “runaway effect” that gave the film so much conceptual depth.

But why is escapism so important to me? Why did I delve into escapism for my film? Isn’t escapism a bad thing?

Well, yes and no. There are two types of escapism, according to psychologist Frode Stenseng. It can be a form of self-suppression when trying to run away from unpleasant thoughts, self-perceptions and emotions, whereas self-expanding escapism allows for positive experiences and discovering new aspects of oneself.

Some social critics warn of attempts by the powers that control society to provide means of escapism instead of improving the condition of the people – “bread and circuses”. It could be in the form endless pleasant stimuli (online pictures of weasels riding woodpeckers and similar) promoting political passiveness and allowing for self-interest capitalism to take over.

But it can also allow societies to improve by imagining utopias and pursuing them via mass cooperation. Social philosopher Ernst Bloch wrote that utopias and images of fulfillment, however regressive they might be, also include an impetus for radical social change. According to Bloch, social justice can not be realized without seeing things fundamentally differently. Something that is mere “daydreaming” or “escapism” from the viewpoint of a technological-rational society might be a seed for a new and more humane social order, as it can be seen as an “immature, but honest substitute for revolution”.

Escapism can provide strength in hard times, as beautifully portrayed in 1970 by Akira Kurosawa’s film Dodes’ka-den, giving characters in extreme circumstances the strength to Persevere.

Some characters get trapped in negative narratives about themselves, like a homeless father who expends more time fantasising about a future mansion then caring for his sick son.

Others however, use it to maintain a more nurturing predisposition: everyday, the main character rides an imaginary trolley in a war-torn city. He keeps idealized, childlike drawings of trolleys in his room. His world is the world of hope for the future.

Others however, use it to maintain a more nurturing predisposition: everyday, the main character rides an imaginary trolley in a war-torn city. He keeps idealized, childlike drawings of trolleys in his room. His world is the world of hope for the future.

We must all escape sometimes – what would life be without it? Perhaps we would be less tolerant of oppression, since we wouldn’t use escapism as a refuge – but also there would be no more daydreams, hopes, aspirations, and better futures imagined. The price of abandoning escapism seems too high to pay.

It’s another one of art’s powerful tools and one of the main reasons people enjoy fiction: it’s a way to transcend everyday life. However, one has to be aware of the cultural context, where postmodern ideology has given up on utopias and instead focuses on immediate self-interest as a way of reaching maximum welfare. This foments suppressing forms of escapism. If there is no better world possible and my satisfaction is the one decent thing I can do, then the way to deal with problems is denialism.

Increased collective interest in the future might initiate positive forms of escapism. Next time you fancy a bit of escapism, consider if the world you are entering is mind expanding or mind suppressing, be it a TikTok video, meme, film or book.

Returning to escapism and Necessary Animals:

Despite my focus on escapism, there are many other themes in Necessary Animals. And that is another thing I like about them – they’re political in a time of apolitical-ness. They are clear about the purpose of their craft – they see a place worth getting to and fighting for and for that they have my undying sympathy.

In sum, NA’s music creates a space for artistic debate – the music is so layered that higher concepts can be considered and discussed. A place where I can see and explore escapism and present it to an audience. For me, there is no escape from escapism.

Bruno Decc is an award-winning Brazilian filmmaker. You can watch Episode 1 of his web series, Out of Place Artefact, starring Ingvild Syntropia and featuring music by Necessary Animals here

Dark Jazz is available to stream or download digitally here