PhD RESEARCH OUTLINE

‘A literary skeleton, plus film illustrations – such, almost without exception, are all films’ – Dziga Vertov[1]

As a filmmaker I have chosen to combine my research with audio-visual recordings that will be made available online in small excerpts, with comment boxes allowing interactive dialogue with visitors to the site. My decision to do this is to provide a mode of participatory ethnography that could entail more agency of the women and men who form the subject of my research. While I acknowledge participatory models of filmmaking, as with Jean Rouch and the screen-back that he developed – that is, integrating feedback from participants into the filmic text (Henley, 2009) – I have decided to instead let my interviewees participate at the editing stage. Thus, they become collaborators, while I assume a role analogous to ‘author’, in which regard David McDougall writes that ‘It is…necessary for visual anthropology to take reflexivity to a further stage—to see it at a deeper and more integral level. The author is no longer to be sought outside the work, for the work must be understood as including the author. Subject and object define one another through the work, and the “author” is in fact in many ways an artefact of the work.’ (MacDougall, 1998: 88-89).

However, Karl G Heider writes in his book Ethnographic Film that the rigour of ethnographic data must take precedence over the artistic ambitions of the ethnographic filmmaker, should they have any – ‘ethnography must take precedence over cinematography.’ (Heider, 1975:4). He goes on to suggest that ‘In ethnographic film, film is the tool and ethnography the goal…sometimes this matter is phrased as an inevitable contradiction between art and science, with filmmakers arguing the case for art, and anthropologists the case for science…Ethnographic film must be judged in relation to ethnography, which is…a scientific enterprise.’

Under Heider’s paradigm then, I position myself as artist-ethnographer. Hence, I diverge from Heider’s formulation by suggesting that ethnographic import can be found in a balance between concerns about ethnographic data and cinematography and film editing. This accords with a general trend in anthropology to abandon the conceit of a scientific enterprise as there is no neutral or objective platform through which to pursue anthropological research (Clifford and Marcus, 1986). However, the historic tensions between ‘scientific enterprise’ and film considered as a serious medium for research in anthropology seemed to hinge on the suspicion that film might be ‘trickery’ (Trinh, 1993:34), or that it represents a lack in depth and rigour; although Michael Stewart, writing in 1994, suggests that film always contains more than its makers intended or realised as the viewer is given the opportunity to construct their own interpretation of events – rather than simply read that of the filmmaker. The value of documentary for Stewart is that it aims at a closer involvement ‘with the reality beyond the image’. As both anthropologist and filmmaker, Stewart is interested in inducing in ones audience ‘a sense of the complex nature of social life’ (Stewart, 1994:472-3).

However, for Fadwa El Guindi, writing in 2004, collaborations between anthropologists and filmmakers produce little of value. Some anthropologists, according to El Guindi, are ‘disdainful’ of an activity that displaces the true goal of the educated mind. Such activities as filmmaking are ‘beneath’ those whose minds should be ‘occupied with ideas’- collaborative work produces little of value, and in rare instances where the work is successful, it is largely ‘accidental’ (El Guindi, 2004:63). Yet in their review of Between Art and Anthropology: Contemporary Ethnographic Practice by Arnd Schneider and Christopher Wright, the authors invoke antipathy towards art forms as part of ethnographic practice as a potential aversion to ‘strategies of research and representation better suited to capturing the sensuous dimensions of experience that usually disappear in the passage from fieldwork to ethnographic text.’[2]

For Margaret Mead, quoted by El Guindi, the idea of film used in serious anthropological research was a potential distraction, if seen as a form of art: ‘if it is an artform, it has been altered’ (Guindi, ibid:36). For Mead, the process of editing or ‘altering’ a sequence of film compromises the ‘exactness and neutrality’ of the data. In terms of my own work, even though I will be posting film clips on a website, I will be paying due attention to organising a series of compiled imagery: there will be cinematic and editorial processes and concerns. This will not simply be instances of ‘vox pop’ compilations, as my interviewees will be concerned that they will be involved in a project that considers due professional process.

In Direct Cinema or observational film, both of which employ long takes, the camera becomes a ‘fly on the wall’, an unobtrusive and all-seeing eye on the world (Beattie, 2004:22). Trinh T Minh Ha’s Reassemblage investigates the assignment of meaning in film as a whole, employing alienating and disruptive sequences where, for example, the audio soundtrack is discontinuous with the visual, leaving an audience unsure as to what is being signified[3]. The film also serves to highlight the dilemma for an audience dependent on authoritative ‘Voice of God’ narration to make sense of the social and cultural activities of the film’s subjects. Trinh’s assertion that ‘there is no such thing as documentary’ (Trinh,ibid:29) implies that even a factual or observational documentary is a constructed assemblage designed to be understood as a mirror representation of reality, which is far from the case.

Former Professor of Anthropology at the University of Papua New Guinea, Andrew Strathern, writes about working for Granada Television between 1973-4 on a series called Disappearing Worlds. At the time, the series was notionally regarded as an exemplar of serious anthropological film watched by millions of people as part of their routine schedule at a time when there were only three UK TV channels. Despite this lack of competition for viewing figures, Strathern found himself making films with a ‘strong human interest’ and, in his words, ‘devices to secure attention’ [my italics] (Strathern, 1976:38). For Strathern, the aim of the series was to provide material that would combine ‘serious understanding’ with content that was commercially viable – something that one potentially might wish to avoid, depending on one’s motivations for making films in the first place. To not try, however, was to polarise the serious and the popular in way that was, ultimately, ‘snobbish’.

In January 2017 I organised an event for Trash Cannes Festival in Hastings. Michael Yorke, former senior lecturer in Anthropology at University College, London screened his 1991 film, Hijra- India’s Third Gender[4], originally commissioned by the BBC for their season of ‘popular’ anthropological films, Under the Sun. In his preamble to the screening, he said that he was enormously proud of the three awards his film had garnered, but that he was also deeply ashamed of it. The reason for this disavowal was that the BBC had insisted that the director abandon his plan to preface his story with a brief history of hijra in rural India, and to explore both their historical and contemporary functions and status in Indian society: he felt he owed this to his audience. Instead, he was coerced into starting the film with a discussion between two friends. Karish has been castrated. His friend Kiran, a truck driver, who is married with two children, longs to follow his example – to become a hijra[5]. When Karish is asked why he had wanted to become a hijra, he pauses, glances briefly at the camera and replies ‘for the homosex’. Mike felt that the coerced inclusion of this segment cheapened his film, insulted the LGBTQI+ community, and betrayed his respondents. Karish’s glance at the camera speaks volumes: he appears to be participating in a process of deception that is at odds with what he believes, and that, on the face of it, makes little sense. He is unwittingly complicit in the construction of a cheap marketing ploy – a device to secure attention.

For both Andrew Strathern and Michael Yorke, the requirements of a system of competing markets in which they were trying to marry serious anthropology with what once might have been termed – or come to be so – ‘infotainment’ or ‘edutainment’, would mean making compromises at the editorial stage. It might be claimed that this was not so much to ‘trick’ their audiences, but to satisfy commissioning bodies focused on financial returns. I would argue that the serious anthropologist is correct in being suspicious of such ploys, and those working in popular media at this level must presumably wrestle with their consciences, or turn down the work.

However, I would argue that far from rendering the data trivial, or compromised, skilful use of filming techniques can work to enhance one’s understanding of the subjects being filmed, as correct or appropriate use of film’s grammatical structures can add layers of meaning unattainable through written text. With film, one can indeed show rather than tell. Through participatory filmmaking subjects can represent themselves; they can be involved in the editing process; via website comment boxes they can potentially engage directly with publics online. This strikes at the heart of what I want to achieve: to explore both the opportunities for a national and even global reach that current internet technologies and platforms enable, and the possibilities inherent in creative practices within ethnographic filmmaking – what Sarah Pink refers to as ‘the materiality and agency of the visual’ (Pink, 2003:180). This will allow my respondents to directly address issues which are central to their senses of self, to respond to challenges to their agency and integrity, and to proactively participate in a debate addressing these concerns.

As Trinh writes, documentary film has the power to reveal ‘powerful living stories, infinite authentic situations’, revealing real people in real situations in the real world – it ‘deals with them’ (Trinh, 1991:33, emphasis author’s own)[6]. By contrast, written text is a bourgeois construction which holds that ‘the means of communication is the word, its object factual’ (Trinh, ibid, 31). In Kirsten Hastrup’s formulation, however, written text is capable of allowing a far more nuanced and exhaustive account of events than real-time media such as film, through its qualities of richness and depth of analysis. Anyone who has seen their favourite novel turned into a film might agree. Yet MacDougall cites potential objection to written text in writing that ‘[p]art of the objection to [earlier] anthropological writing has stemmed from its assumption of authority and its techniques for making its conclusions appear natural and indisputable’ (MacDougall,2006:44).

Bill Nichols wrote that ‘[A]t the moment we believe we are stalking signs, we may suddenly discover that we ourselves are being stalked…the big game is ideology and what it does to us’ (Nichols 1981: 10). What the viewer makes of these coded representations depends largely on processes associated with interpreting signs and significations through referral to one’s experience rooted in the past. How does ideology play a part in all this? If Nichols is correct, it is the ideology of the dominant class[7] that drives or directs what the viewer understands of the sequence of images. As David MacDougall observes, ‘images are not in any sense knowledge – they simply make knowledge possible’ (MacDougall, ibid:4).

I would argue that film bears what I have termed the ontological thumbprint of real-time, real-world events; that the assignment of meaning in written text is shaped ideologically according to the same subjective editorial framework as film, and that mediation is an inevitable part of the process of the use of film as representation and should be welcomed as such. As Afsaneh Najmabadi writes of ‘the ethnographic venture’, ‘as historians…we select some texts and ignore others, producing relevance as we go’ (Najmabadi: 2014, 13).

METHOD AND ETHICS

‘Corporeal images are not just the images of other bodies, they are also the image of the body behind the camera and its relations with the world’ – David MacDougall[8]

So, where does my own research fit into all this? What should I be aware of in terms of representation, ownership and dissemination of knowledge? What ethical concerns should I bear in mind? What are the implications – if there are any of pressing note – of speaking on behalf of a group of women and men from my close personal network?

The short films I propose to make will follow the paradigm of an observational documentary film, as outlined by Bill Nichols, who describes the observational mode as that which emphases ‘a direct engagement with the everyday life of subjects as observed by an unobtrusive camera’ (Nichols 2010:31). I have chosen the observational mode as it seems to me to be, of all the available modes, the most direct approach to gathering data. I will not be making films with a ‘look’ that attempts to posit my work as a largely commercial enterprise, with all its associated methods and tropes. My approach will be, as suggested earlier in this outline, to create dialogues between myself, the ‘author’ and my interviewees, the ‘characters’ or storytellers. Central influences on my filmic style are the Russian director of fiction Andrei Tarkovsky, who is renowned for his modus operandum of allowing time to unfold before the camera, of eschewing rapid cuts and other disorienting tropes or techniques; and British documentary filmmaker Marc Isaacs, whose film The Lift observed residents of a tower block in Hackney, focusing on his interactions with the residents as they entered and left the lift[9]. Leaving the camera running for long takes will give the films a chance to ‘breathe’ – to allow time to pass in a non-coerced manner, which I hope will engender natural, spontaneous responses to my questions. As Trinh remarks, the use of wide-angle lenses places the events in context, while the close-up is suspect because of its partiality: the one is objective, the other subjective (Trinh, ibid:34). Yet I would argue that the close-up affords greater intimacy with the subject, and it is in those intimate moments when one might approach a kind of emotional authenticity – even if that authenticity is constructed.

At this stage, I aim to separate my work into about seven discrete segments, with each ‘story’ lasting approximately six minutes – the exact number is to be determined during and after the fieldwork process and period. These will be uploaded to a website, with text outlining the nature and purpose of the project. Comment boxes will allow visitors to the site to upload their own reflections, questions or comments. Site administration will allow the monitoring of these responses before they appear on the site, allowing me to filter out any instances of ‘trolling’, prejudice or hate speech – sexism, racism, homophobia, misogyny or discrimination based on religious faith or belief. I am proposing that the films allow each interviewee to outline their experiences of living in society as a person who has chosen to be childfree, or has come to that choice through circumstance, conviction, intention or omission. Initial interviews will be informal, and in surroundings that are conducive to relaxed responses: once a pattern emerges with these initial interviews, my questioning will become more directly focused on issues raised. No-one will be asked questions about the intimate circumstances of their lives. I will leave them to tell me if they think it is relevant. My initial task is to gain their confidence, and provide a space where they can talk freely about their experiences of attitudes and responses from friends, family, partners, work-mates, health professionals, clergypersons or colleagues relating to their decisions not to have children. As already outlined in my introduction, contextual visualisation will be intercut with the interviews and will show the respondents at home, at work, at leisure. It is naturally impractical to anticipate in advance where my leading questions will take us, as I will not simply be looking for responses adhering to a strict formula. I am referring to past experience with my previous documentary films to anticipate that further or related topics for discussion will emerge as a result of the interviews, and that these in turn will shape the overall direction of each film.

As indicated earlier, my interviewees are people of my close acquaintance, or in two cases people who have self-selected because they appreciate my interests and/or my intentions. We have established mutual trust: if this were not the case, I would not invite them to participate or collaborate. My device to secure any kind of attention will be the topic itself, underpinned by what Wilma de Jong describes as ‘a strong drive, a passion that signifies the filmmaker’ (de Jong 2012:176). It is my intention not to speak for my interviewees, or to present an authorative stance through ‘Voice of God’ narration or exposition, but to let them speak for themselves, and thus to contest and re-narrate stereotypical notions of what it means to be childfree.

Where possible, I intend to spend an initial weekend with each interviewee, when they have most time free from their work obligations, to establish a working method, to put them at ease with the filming process, and film initial responses to my questions. I will then arrange further days when we both watch the footage I have captured. I will encourage my interviewees to give me their reactions to what has been filmed: does it capture succinctly and accurately what they meant to say? Is it a fair representation of their viewpoint or response to each question raised? If, in the time that has elapsed since our first interview session, they have had time to reflect, to expand on topics raised, or points germane to the discussions, I will suggest we film new interviews. If they want anything removed, or improved upon, this will be done in accordance with their wishes. I will also show them, as time goes on and I have more segments captured, interviews with other respondents. If they want to respond to points raised or views expressed, I will film them doing so. In this way, each respondent can enter a dialogue with members of their cohort.

Questions which I anticipate may become germane to the overall project might examine central themes: What connects my respondents? What differentiates them? Is there among them a common viewpoint or set of assumptions about the world, or their experiences, that would help explain their individual choices? Are they united in opposition to any set of expectations that may have been imposed upon them, or implicitly or explicitly demanded of them – that they become, for instance, ‘procreative serfs’? To what extent are they, to use Henrietta Moore’s phrase, ‘the authors of their own experience’ (Moore 1994:35)? Had they identified their childlessness as a societal issue? Do they feel they have anything in common with other childfree persons, in a general sense, not just with others from their cohort? Are their choices formulated in accordance with – or opposition to – a set of beliefs or practices with which they identify?

Throughout the research I will be self-reflexive and question my positionality. My reasons for pursuing a research degree are, no doubt predictably, the results of a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Although there are several anthropological journal entries, and books on the popular market dealing with practical and ethical concerns relating to the rejection of motherhood, the issue of societal attitudes to the childfree is an under-represented area of research in visual anthropology: a thorough search of internet databases, in both academia and mainstream or popular culture, has revealed only a single film made on this topic, a French-Canadian production called Maman? Non Merci! [10] The Vimeo trailer for this documentary film translates the title as No Kids For Me, Thanks! The film’s style mirrors that of hybrid ‘popular anthropology’ and populist documentary, described by Philip Vannini as a kind of ‘non-academic ethnographic documentary [that] has become a commonly practiced and widely recognized feature of popular film culture’ (Vannini 2015:392 ). Vannini goes on to reflect that in respect of such works ‘one could venture to say that “amateur” or “self-fashioned” ethnographers have outshone their “professional” academic counterparts, at least in the domain of popular reach’ (ibid, 393).

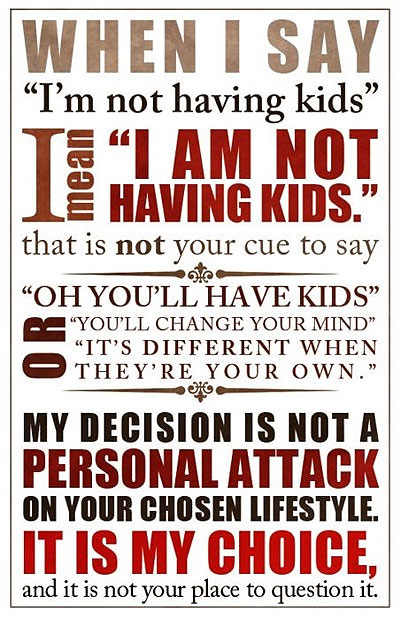

Further motivations for pursuing my research topic include the desire for continuing to learn as I approach my retirement years. My friend, long-term mentor and Harvard Fellow George Balamoan has encouraged me in this over the last 20 years. In 1988, after I had copy-edited his book Blue Nile Boy, a semi-autobiographical account of his childhood under British administration in post-war Sudan, George encouraged me to pursue a career in academia[11]. There is also an even more personal dimension: my long-term partner Amanda Thompson has known since the age of seven that she did not want children. Despite this, aged 35, she began to be challenged by certain of her female friends, who advanced a series of entreaties such as ‘you still have time’, ‘you’ll regret not having one’, ‘you know you want one really’, and so on. These progressed ultimately to ‘God gave you a woman’s body, you should use it.’ This came from people who professed no religious faith in any other context, and seemed to see the Church as a booking agency for colourful ritual pageantry – a ceremonial referral service for births, deaths and marriages. Amanda greatly resented these incursions on her privacy, challenges to her integrity and refusals of her right to live her life according to her choices or convictions. Yet her friends remained intransigent: she would never be ‘one of them’; she had let the side down.

I myself have two children, a daughter aged 40 and a son aged 23 from an earlier relationship. Following the collapse of my relationship with my daughter’s mother, I was estranged from Amy for 15 years. We now enjoy a healthy and honest relationship, acknowledging the trials of the past, but focusing on our lives as they move forward. For my friends who have elected not to have children, or who are without them for reasons of circumstance or opportunity, these are simply facts of our respective lives. There is mutual respect for our choices. As noted earlier in this outline, many of my friends work in areas where to be childfree is not unusual, owing in part to the strictures placed on their lives by their career choices or lifestyles. I suspect, however, that attitudes among their friends and family may differ: as Park remarks, ‘[i]ndividuals who possess a stigmatized identity are faced with the ongoing tasks of accepting it themselves and negotiating it in interactions with others who may view their character and behaviour as incomprehensible, strange, or immoral (Park, 2002:21)’.

In the matter of such stigmatisation, Erving Goffman remarks that once criticism has been applied, there is a tendency to ‘impute a wide range of imperfections based on the original one’ (Goffman, 1963:5). It is my curiosity to understand the experiences of childfree persons in contesting attitudes such as these that will form an essential component of my research.

TIMETABLE

I plan to begin filming in September 2021, and to have principal photography, editing and sound mix complete by January 2022. I will then organise what I have captured into discrete segments, one short film per interviewee or interviewees, and where appropriate I will invite my interviewees to expand upon points they will have made, and to respond, where applicable, to responses from others from their cohort. Any adjustments, corrections or changes will be complete by April 2022. I will then build a website that features each segment with brief background or biographical data, and, as indicated earlier, text outlining the origination and purpose of the site. Examples of the kind of website I will build include http://www.laygatestories.com and https://www.opendemocracy.net/article/i_am_an_american_portraits_of_post_9_11_us_citizens I will then embark on completing my 40-50,000 word dissertation, which will be formed from my ongoing field notes and journal entries, to be completed by May 2024.

BIBLIOGRAPHY, REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

BOOKS and JOURNALS:

Afshani, Sayed Alireza, ‘The attitudes of infertile couples towards assisted reproductive techniques in Yazd, Iran: A cross sectional study in 2014’, International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine, December 2016, 14 (12) 761-768

Akundy, Anand, Anthropology of Aging. Contexts, Culture and Implications, Serials Publications, Delhi, 2004

Arya, Shafali Talisa & Dibb, Bridget (2016) ‘The experience of infertility treatment: the male perspective’, Human Fertility, 19:4, 242-248

Atwood, Margaret, Good Bones, Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd., London, 1992

Austin, Thomas and de Jong, Wilma (editors), Rethinking Documentary. New Perspectives, New Practices, Open University Press, 2008

Banks, Marcus and Morphy, Howard, Rethinking Visual Anthropology, Yale University Press UK, 1999

Barbre, Joy Webster, ‘Meno-Boomers and Moral Guardians: An Exploration of the Cultural Construction of Menopuase’, in Weitz, Rose (editor), The Politics of Women’s Bodies, Oxford University Press, New York, 2003

Barnard, Ian, Queer Race. Cultural Interventions in the Racial Politics of Queer Theory, Peter Lang, New York, 2004

Basten, S., Voluntary childlessness and being Childfree. The Future of Human Reproduction: Working Paper #5, St. John’s College, Oxford & Vienna, Institute of Demography 2009

Baumgardner, Jennifer and Richards, Amy, Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism and the Future, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2000

Beard, Mary, Women and Power: A Manifesto, Profile Books, 2017

Bell, Amelia Rector, ‘Separate people: speaking of Creek men and women’, American Anthropologist, 92:332-45

Benatar, David, ‘Better Never to Have Been’. Oxford University Press, 2006

Boyce, Paul and Hajra, Anindya, ‘Do you feel somewhere in light that your body has no existence? Photographic research with transgendered people and men who have sex with men in West Bengal, India’, Visual Communication, February 2011, Vol. 10 (1), pp3-24

Burke, Lynda, Feminism and the Biological Body, Edinburgh University Press, 1999

Butler, Judith, Gender Trouble, Routledge, New York, 1990

Butler, Judith, Undoing Gender, Routledge, Oxfordhsire, 2004

Cain, Madelyn, The Childless Revolution. What It Means to be Childless Today, Da Capo Press, Washington, 2002

Campbell, Elaine, The Childless Marriage. An Exploratory Study of Couples Who Do Not Want Children, Tavistock Publications, London, 1985

Clifford, James and Marcus, George E., Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, University of California Press Ltd, London, 1986

Connell, R.W., Gender, Polity, Cambridge, 2002

Correa, Sonia, ‘Sexuality, Gender and Empowerment’, Development, 53(2), 183–186, 2010

Coward, Rosalind, Female Desire, Paladin Books, London, 1984

De Beauvoir, Simone, The Second Sex, Vintage Classics, 1977

Daum, Meghan, Selfish, Shallow and Self-Absorbed. Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids, Picador, New York, 2015

de Jong, Wilma, Knudsen, Eric and Austin, Thomas, Creative Documentary. Theory and Practice, Pearson Education Ltd, 2012

DeMarneffe, Daphne, Maternal Desire: On Children, Love, and the Inner Life, Back Bay Books/Little, Brown, and Company, 2005

Deeb, Lara, An Enchanted Modern: Gender and Public Piety in Shi’i Lebanon, Princeton University Press, 2006

Dreifus, Erika, No Kidding: Women Writers on Bypassing Parenthood, Seal Press, 2013

Dreifus, Erika, Unmothers: Writing About Life Without Children, The Missouri Review, Volume 37, Number 33, 2014, pp 186-196, accessed 27.08.16

Edelman, Lee, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Duke University Press, London and Durham, 2004

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M., ‘Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage’, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005

El Guini, Fadwa, Visual Anthropology. Essential Method and Theory, Alta Mira Press, 22004

Eliot, George, Middlemarch, Penguin Classics, London, 1994

Eliot, T.S., The Wasteland, Faber and Faber, 2002

Erikson, Erik, Childhood and Society, W W Norton, 1963

Foucault, Michel, The History of Sexuality, Volume One, Pantheon, New York, 1978

Foucault, Michel, ’Power and Norms’ in M.Morris and P.Patton (ed), Power, Truth and Strategy, Feral 1979 (Sydney),p 62

Funke, Jana, review: Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Third Space, A Journal of Feminist Theory and Culture, Vol 10, 2011

Gannon, Linda, Women and Aging. Transcending the Myths, Routledge, London, 1999

Gillespie, Rosemary. Choosing Childlessness: Resisting Pronatalism and the Emergence of a Childless Femininity. University of Southampton, Southampton, 1999

Gillespie, Rosemary, ‘Contextualizing voluntary childlessness within a postmodern model of reproduction: implications for health and social needs’. Critical Social Policy, Vol 21(2),pp 139-159, 2001

Gillespie, Rosemary,’ When No Means No: Disbelief, Disregard and Deviance as Discourses of Voluntary Childlessness’, Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 223–234, 2000

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins, The Man-Made World: Or, Our Androcentric Culture, Cornell University Library, 2009

Goffman, Erving, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identit, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963.

Halberstram, Judith, Female Masculinity, Duke University Press, 1998

Heider, Karl G, Ethnographic Film, University of Texas Press, 2006

Heitlinger, Alena, ‘Pronatalism and Women’s Equality Policies’, European Journal of Population Vol. 7, pp343–75, 1991

Hook, Derek (2006). Lacan, the meaning of the phallus and the ‘sexed’ subject, London: LSE Research Online, accessed 24.09.16

Irigary, Luce, This Sex Which Is Not One, Cornell University, 1985

James, P.D., The Children of Men, Faber and Faber, 2010

Keizer, R. (2011), ‘Childlessness and Norms of Familial Responsibility in the Netherlands’, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 1, 424, pp421-438

Kildea, Gary and Wilson, Margaret, ‘Interpreting Ethnographic Film: An Exchange About ‘Celso and Cora’’, Anthropology Today, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 15-17, 1986

Korasick, Candice A., Women Without Children. Identity, Choice, Responsibility, University of Missouri-Columbia, 2010

Korasick, Candice A., Women Without Children. Identity, Choice, Responsibility, University of Missouri-Columbia, 2010

Koropeckyj-Cox, Tanya and Call, Vaughn R. A. ‘ Characteristics of Older Childless Persons and Parents. Cross-National Comparisons’, Journal of Family Issues, Volume 28 Number 10, October 2007, pp 1362-1414

Koropeckyj-Cox, Tanya, Romano, Victor and Morafound, Amanda, ‘Through the Lenses of Gender, Race, and Class: Students’ Perceptions of Childless/Childfree Individuals and Couples’, Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007, p415

Kostenberger, Andreas, ‘The Bible’s Teaching on Marriage and Family’, www.frc.org, accessed online 08.07.17

Leonard, Kristy M, ‘Her Body, No Baby: Compulsory Procreativity, the Stigma of Childlessness, and U.S. Exceptionalism in the Era of Technoscience’, Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 2012

Leone, Catherine, ‘Fairness, Freedom and Responsibility: The Dilemma of Fertility Choice in America’, Washington State University ,1989

Letherby, G, ‘Childless and bereft?: Stereotypes and realities in relation to voluntary and involuntary childlessness and womanhood’, Sociological Inquiry,72, 7-20, 2002

Letherby, Gayle, ‘Mother or Not, Mother or What?: Problems of Definition and Identity’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 17: 525-532, 1994

Letherby, Gayle, ‘Other than Mother and Mothers and Others: The Experience of Motherhood and Non-Motherhood in Relation to ‘Infertility’ and ‘Involuntary Childlessness’’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 22: 359-372, 1999.

Livingston, Gretchen and Cohn, D’Vera, ‘Childlessness Up Among All Women; Down Among Women with Advanced Degrees’, Pew Research Center, 2010

Loether, Herman J, Problems of Aging. Sociological and Social Psychological Perspectives, Dickenson Publishing, California, 1975

MacDougall, David, Film, Ethnography and the Senses. The Corporeal Image, Princeton University Press, 2006, p3

MacDougall, David, Transcultural Cinema. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998

Mahmood, Saba, Politics of Piety. The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject, Princeton University Press, 2005

May, Elaine Tyler, Barren in the Promised Land: Childless Americans and the Pursuit of Happiness, Basic Books (New York), 1995

Miller, Seumas, Foucault on Discourse and Power, Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory no 76, The Meaning of 1989, October 1990, pp 115-125

Monach, James H., Childless: No Choice. The Experience of Involuntary Childlessness, Routledge, London, 1993.

Moore, Henrietta, A Passion for Difference, Polity Press, 1994

Morgan, S. P., & King, R. B. ‘Why have children in the 21st century? Biological predisposition, social coercion, and rational choice’, European Journal of Population, vol.17, pp3-20, 2001

Najmabadi, Afsaneh, Professing Selves, Duke University Press, 2013

Nichols, Bill, Ideology and the Image. Social Representation in the Cinema and Other Media, Indiana University Press, 1981

Nichols, Bill, Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001

Ortner, Sherry, ‘Is Female to Male as Nature Is to Culture?’, in M.Z. Rosaldo and L. Lamphere (eds), Woman, Culture and Society, Stanford CA, Stanford University Press, pp 68-87.

Overall, Christine, Why Have Children? The Ethical Debate, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2012

Park, Kristin, ‘Stigma management among the voluntary childless’, Sociological Perspectives, Volume 45, Number 1, pages 21–45, 2002

Pilcher, Jane and Whelelan, Imelda, 50 Key Concepts in Gender Studies, Sage Publications, London, 2004

Pink, Sarah, ‘Analysing Visual Experience’, in Research Methods for Cultural Studies, Michael Pickering (editor), Edinburgh University Press, 2008

Pink, Sarah, Doing Sensory Ethnography, Sage Publications, London, 2009

Pink, Sarah, Interdisciplinary agendas in visual research: re-situating visual anthropology, Visual Studies, Vol 18, No 2, 2003, pp

Pink, Sarah, The Future of Visual Anthropology. Engaging the Senses, Routledge, London, 2005

Pollitt, Katha, ‘Fetal Rights. A new assault on Feminism’, Weitz, Rose (editor), The Politics of Women’s Bodies, Oxford University Press, New York, 2003

Pullen, Alison, Thanem, Torkild, Tyler, Melissa and Wallenberg, Louise, in ‘Gender, Work and Orgainisation’, Vol 23, Issue 1, 2015

Rabiger, Michael, Directing the Documentary, Focal Press, 2009

Renov, Michael, Theorising Documentary, Rouledge, London, 1993

Restivo, Angelo, Review: No Future. Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Georgia State University, 2004

Sadl, Zedenka and Ferko, Tajda, ‘Intersectionality and Feminist Activism: Student Feminist Societies in the United Kingdom’, www.fdv.uni-lj.si, 2017, accessed online 17.10. 18

Stewart, Michael, Review: Linking Film and Anthropology: The State of the Art by Peter Ian Crawford and David Turton, Current Anthropology Vol 35, No 4, pp 472-474, The Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, accessed 22.02.17

Stoneley, Peter, ‘Children, futurity, and value: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’, Textual Practice, 30:1, pp169-184, 2016

Strathern, Andrew, ‘Making ‘Ongka’s Big Moka’’, Cambridge Anthropology – special issue, Ethnographic Film, 1984

Stulhofer, Aleksander and Sandfort, Theo, Sexuality and Gender in Postcommunist Eastern Europe and Russia, Haworth Press, New York, 2005

Thomas, Candice L. , Laguda,Emem, Olufemi-Ayoola, Folasade, Netzley, Stephen, Yu, Jia and Spitzmueller, Christiane, ‘Linking Job Work Hours to Women’s Physical Health: The Role of Perceived Unfairness and Household Work Hours’, Sex Roles, October 2018, Vol 79, Issue 7-8, pp 476-488

Trinh T Min-ha, ‘The Totalising Quest of Meaning’ in Renov, Michael, Theorizing Documentary, Routledge, London, 1993

Utterson, Andrew (editor), Technology and Culture. The Film Reader, Routledge, Oxford, 2005

Valentine, David, Imagining Transgender. An Ethnography of a Category, Duke University Press, 2007

Vannini, Philip, ‘Ethnographic Film and Video on Hybrid Television: Learning from the Content, Style, and Distribution of Popular Ethnographic Documentaries’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Vol. 44, pp392-3, 2015

Vaughan, Dai, For Documentary: Twelve Essays. Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 1991

Veevers, Jean, Childless by Choice, Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd, 1980

Walker, Anita M. and Dickerman, Edmund H., ‘A Woman under the Influence: A Case of Alleged Possession in Sixteenth-Century France’, The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Autumn, 1991), pp. 534-554, accessed 23.08.16

Weitz, Rose, The Politics of Women’s Bodies, Oxford University Press, New York, 2003

FILM

Becoming Penny, Keith Rodway, the Other Film Company/Trash Cannes Films, 2017

Brother’s Keeper, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinovsky (directors), Creative Thinking International Ltd, 1992

Children of Men, Alfonso Cuaron, Universal, 2007

Divorce Iranian Style, Kim Longinotto, Twentieth Century Vixen, 1998

Gimme Shelter, Albert and David Maysles, 20th Century Fox, 1971

District 9, Neill Bloomkamp, Tristar Pictures, 2009

Hijra – India’s Third Gender, Michael Yorke, 1991

Maman? Non Merci!, Magenta Maribeau, 2015

Mirror Mirror directed by Zemirah Moffat, 2006 (London, England: Royal Anthropological Institute, 2007)

Reassemblage, Trinh T Minh-ha, Institute for Film and Video Art, 1982

Titicut Follies, Frederick Wiseman, Zipporah Films, 1967

Walk the Line, James Mangold, 20th Century Fox, 2005

[1]Utterson, Andrew (editor), Technology and Culture. The Film Reader, Routledge, Oxford, 2005, p100

[2] Schneider, Arnd and Wright, Christopher, ‘Between Art and Anthropology: Contemporary Ethnographic Practice’, Journal of Museum Ethnography no. 25 pp. 195-204, Museum Ethnographers Group, 2012

[3] Reassemblage, Trinh T Minh-ha, Institute for Film and Video Art, 198

[4],Michael Yorke, Hijra – India’s Third Gender , BBC Films, 1991

[5] For a discussion on transgendered people and men who have sex with men in West Bengal, India, I refer to Paul Boyce and Anindya Hajra’s work on this subject (Boyce and Anindya, 2011)

[6] Trinh T Min-ha, ‘The Totalising Quest of Meaning’ in Renov, Michael, Theorizing Documentary, Routledge, London, 1993

[7] I refer here to Marxist understandings of ideology as consisting of certain social ideas which periodically dominate in class-divided societies.

[8] MacDougall, David, Film, Ethnography and the Senses. The Corporeal Image, Princeton University Press, 2006, p3

[9] Marc Isaacs, The Lift, Dual Purpose Productions, 2001

[10]Magenta Baribeau, Maman? Non Merci!, Groupe Intervention Vidéo, 2015

[11] Balamoan, George, Blue Nile Boy, Karia Press, London, 1989

Keith Rodway