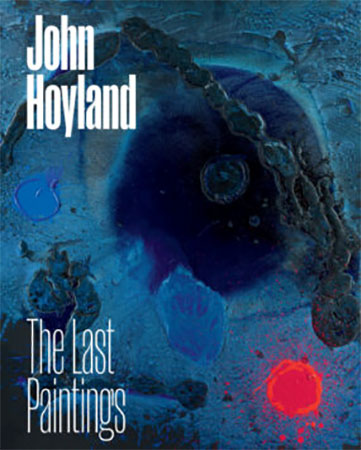

John Hoyland. The Last Paintings, eds. Sam Cornish, Sophie Kullmann, Wiz Patterson Kelly (£35, ridinghouse)

Sometimes you get art books to reaffirm your interest and further your understanding of an artist, other times for reproductions of work that are hard to see in real life, occasionally to be convinced and have your mind changed. John Hoyland. The Last Paintings is one such book for me. I am not alone in being bewildered by the explosions of plastic colour over stained floods of dark metallics which constituted Hoyland’s later work. In reproduction, his colours are still vivid and startling, exciting even; see the pictures in the flesh and the paint often looks like squeezed-out toothpaste in a messy bathroom. All too many of them work around a central circular motif, which feels like an easy resolution as a focus for the viewer. Just how did the master of subtle stained canvasses and then complex layered abstraction – I’m a huge fan of Hoyland’s earlier work – arrive at this energetic and somewhat casual way of working?

Mel Gooding’s essay is especially useful for a doubter like me. He discusses Matisse’s use of ‘black-as-light’, along with Turner’s ‘smoke and shadow’, as colour but also as an elegiac device, often specifically linked to the death of Hoyland’s friends and fellow artists. Gooding also discusses Hoyland’s fascination with astronomy and cosmology, black holes and the big bang of creation at the centre of the universe. This certainly allows us to understand some of the motifs that informed and inspired Hoyland’s late paintings, and perhaps the mood and thought processes at work, but it doesn’t of course change the paintings.

David Anfam writes more exuberantly about Hoyland’s art. He uses the word ‘pizzazz’ at the start of his essay, and declares that ‘Disparities and extremes are rife: terrestrial risk, celestial realms, sensuousness, violence and valediction.’ Again, there are comparisons with space, although this time the elegaic reference is to Dylan Thomas urging the readers of his poem to ‘rage against the dying of the light’. Comparisons with Van Gogh make less sense to me, but Anfam shows us pages from Hoyland’s scrapbooks which include reproductions of van Gogh’s work (Hoyland was apparently always a fan), and charts Hoyland’s journey from staining formalist to expressionist gestural pattern and mark maker, offering the likes of Jules Olitski, Robert Motherwell, Mark Tobey, Barnett Newman and others for artistic context and example. In the end, however, Anfam comes back to cosmology and colour, excitedly calling Hoyland ‘a painterly pyrotechnician’ and declaring that he has done in paint what Mahler did in sound.

Vincent van Gogh is also the initial focus of Natalie Adamson’s writing here, or rather a group of paintings which Hoyland dedicated to him. Again, elegy is mentioned alongside tribute, and Adamson contrasts and compares Hoyland’s ‘Vincent’s Garden’ painting with van Gogh’s ‘Garden of the Asylum’. I’m afraid I find it hard to see Hoyland’s vivid small painting as an ‘Edenic garden of modern painting’, and even harder still to take the clumsy dripping humanoid form which features in ‘Vincent (A Memory)’ seriously. Again, Adamson offers us an insight into Hoyland’s inspirations and ideas, but avoids critical discussion of the actual art that Hoyland creates.

It’s with some relief, then, that I turn to Matthew Collings and his piece which answers the title question: ‘John Hoyland: What Are We Seeing?’ Collings writes from a no-nonsense personal engagement with Hoyland’s work, admitting that it was only eventually that he ‘began to see the subtlety and depth of his earlier pieces in the new style of work he was doing’, having previously observed that the paintings looked ‘violently vulgar: his use of unmixed colours, kitschy imagery of exploding galaxies’. (Which is kind of where I still am with them.) Collings briefly discusses formalism in Hoyland’s earlier work but then unfortunately moves away from engagement with the art to mostly discuss Hoyland as artist, as a character, a macho heavy drinker who chose freedom rather than constraint within the art world. Much of Collings’ essay here clumsily conflates artist and art, and spends several pages charting the public response to Hoyland’s work over the decades.

I am not convinced by Colling’s suggestion that ‘with the late works you are looking at knowledge and chance’ or that the suggestion that Hoyland’s ‘aim was always to bring jazzy, interesting differences – shadowy shapes, glowing discs and sparkling darkness – into an effective unity’ is enough. Nor is ‘looseness and freedom’ or working ‘to make things buzz visually’. For me I can’t get away from the negative connotations of what Collings calls ‘weird brashness and tastelessness’, not because I think painting should be tasteful but because I am still aghast at the plasticity and formlessness of the work. There’s no denying that the late work by the same artist who used to paint a different sort of work must have some relationship to that earlier work, but it doesn’t mean it’s as good as, as intelligent as, as well painted or as interesting.

This is a fascinating and beautifully produced book, and it will continue to intrigue me and help me engage with these John Hoyland paintings which I struggle with. Perhaps this is how it should be? One of the most interesting ‘Quotes from a Life’ in the book is Hoyland’s own declaration that ‘The only artists who really interests me […] are the ones who terrify me – that is, who are threatening in their ability.’ Hoyland’s later paintings intrigue because of the way they threaten not only the viewer and their expectations, but also the artist’s own reputation and previous work. I still have some catching up to do.

Rupert Loydell